Business Sectors

Events

Contents

OPA 90 limited by lack of emergency vessels

US near-shore navigation and emergency response plans need practical and enforceable standards to maximise safety and reduce incident risks, while improved pilotage schemes are seen as a major enhancement to sailing in confined waters

Whether a tanker is being navigated into port by utilising the services of a pilot, or towed by an escort tug, the safety regulations which apply have to strike a balance between an ideal outcome and what is realistically possible. In the salvage and escort tug sector there have been concerns that the final rule of the US Oil Pollution Act (OPA) of 1990 is too prescriptive. Entering into force on 31 December 2008, this rule means that the manner in which owners must plan for salvage has changed dramatically.

According to Mauricio Garrido, European and US general manager for emergency response provider, T&T Bisso, “The new regulation institutes a regime for owners to select and pre-contract a salvage and fire-fighting provider for each of the Captain of the Port (COTP) zones where they trade or may trade. So the burden is on the owner to select the right company and to certify that this contractor is adequate to meet the intent of the regulation – which requires that owners name a specific tug at every port with adequate horsepower.”

The difficulty with meeting these standards is that there is just one emergency towing vessel operating in US coastal waters, in Neah Bay, Washington. “Perhaps the US government thought that the industry would fund this and that shipowners would contract tug operators to build a number of vessels; however, this is not achievable in today’s market.

“So basically, what owners and contractors have to do is to study the available resources and plan with those to achieve the best response possible,” said Mr Garrido. “Had the US government come out and said, ‘We are going to spend US$300 million to create some shipbuilding jobs; we are going to build 20 tugs’, then the industry could have bid competitively to operate the vessels and then repaid the government at a later date to reimburse the taxpayer. That would have made a lot of sense – maybe too much sense!”

While this set of rules affecting near shore navigation was finally issued at the end of 2008, another has been agreed with IMO in June this year, which is intended to improve the safety of pilots transferring on to vessels. As Nick Cutmore, secretary general of the International Maritime Pilots’ Association, explained, “In 2006 eight of our members died due to ladder accidents and many more were injured.

“We asked IMO to change the relevant regulations in Solas and we now have proposals agreed but they have to be ratified. These need to go through MSC and then to the assembly, so they will not enter force until 2012 but we are still happy to have achieved that. Pilotage is acknowledged at IMO as being the single biggest step that can be taken to enhance navigation in confined waters.

“Intertanko supported us through this process; it is an organisation that also recognises the benefits that a pilot can bring to the bridge.” Furthermore, Intertanko has recently called for the consideration of deepsea pilots in the Malacca Straits, since it is a densely trafficked area.

Another current worry for pilots is the effect of the Standards of Training, Certification & Watchkeeping (STCW) code, with some in the industry privately expressing fears that this has ‘dumbed down’ the requirements for crew qualifications. “The most concerning thing for pilots at present is the decline in standards of bridge crew,” said Mr Cutmore.

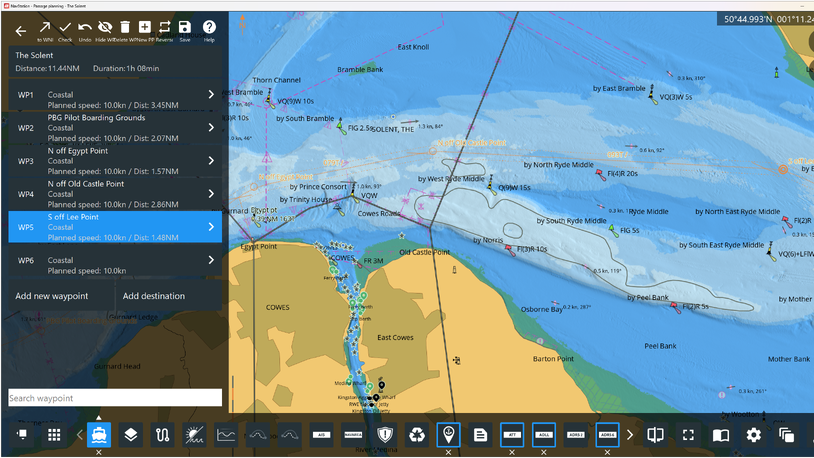

“Pilots have to adapt to new technology, such as ecdis, and there have been instances where a pilot has gone on board a ship and started adjusting the ecdis, and the crew have looked on amazed and said, ‘We did not know how to do that’. The pilot, who might have had to deal with 20 different types of ecdis system, will then be running a tutorial for the crew!”

Mr Cutmore also has reservations about IMO’s proposed e-navigation scheme, which aims to integrate existing and new navigational tools, in particular electronic tools, in an all-embracing system that will contribute to enhanced navigational safety. “Our association is watching the project unfold with interest but we have concerns that it is turning into another ecdis exercise, becoming hugely complex and over-specified, when its origins were to harmonise bridge interoperability.

“We have waited 25 years for ecdis, and e-navigation could go down the same path.” TST

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Environmental Protection Webinar Week

Cyber & Vessel Security Webinar Week

The illusion of safety: what we're getting wrong about crews, tech, and fatigue

Responsible Ship Recycling Forum 2025

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.