Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

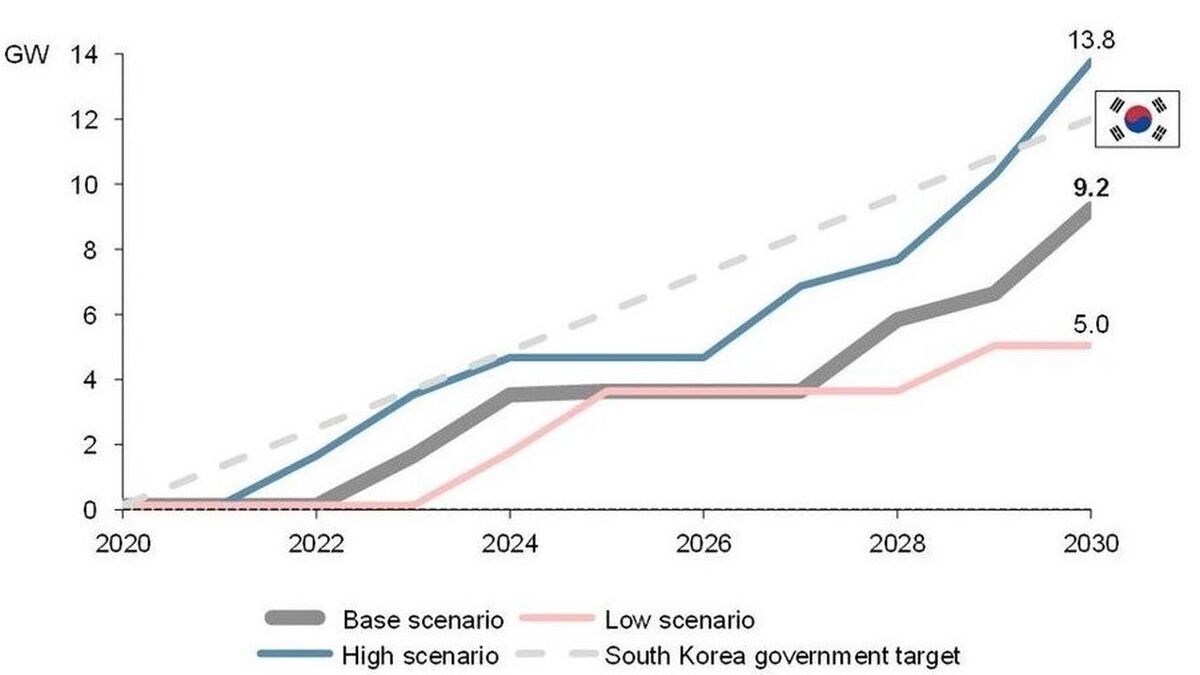

South Korea ‘unlikely to meet’ ambitious 12-GW offshore wind target

Market conditions in South Korea are such that the country is unlikely to meet its ambitious goal for offshore wind capacity by the end of decade, a leading industry analyst believes

On a visit to an offshore wind project in the North Jeolla region of the country earlier in 2020, South Korea President Moon Jae-in said his government’s goal “is to become one of the world’s top five offshore wind energy powerhouses by 2030.”

Offshore wind was ‘carved out’ as a priority area in South Korea’s Green New Deal, announced in July 2020. A dedicated implementation plan for offshore wind was subsequently released.

“In order to reach its goal, the government needs to have 12 GW of offshore wind by 2030,” said Aegir Insights in a newly-published report.

However, the company believes the support mechanism for offshore wind projects, the RPS scheme, under which generators obtain Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) for capacity traded in the market, is too complex and does not provide developers with sufficient certainty. In its view, this means the 12-GW target is unlikely to be met.

“The government could reduce complexity and uncertainty by replacing the RPS with a simpler fixed feed-in tariff mechanism,” said Aegir.

RECs are issued by Korea Energy Agency at a price determined by the power produced and a multiplier applied to it, based on energy type. Offshore wind’s multiplier is dependent on distance to shore: a greater distance from shore is awarded a higher multiplier.

“The Korean New and Renewable Energy Center will determine if a windfarm is eligible for RECs and what multiplier it is eligible for. RECs can be traded on the market, however as this entails uncertainty; a more favourable alternative for developers would be long-term contracts with power producers,” Aegir Insights explained.

In the South Korean government’s build-out plan, most capacity in the long-term is expected to be built in the regions South Jeolla and Ulsan, the latter being suitable for floating projects. In South Jeolla, a substantial area suitable for fixed-bottom project exists with wind resources of 8-8.5 m/s, similar to wind speeds in Ulsan.

Several projects have already acquired a licence with around 3 GW expected to be installed before 2025. In addition to these already licenced projects, a further 4.5 GW, 3 GW of which is government-backed, is expected to be operational by 2030.

Aegir Insights said development lead times are assumed to be five years, unless major delays occur, but to-date projects have required extended timelines of 8-11 years from first permit to COD.

Aegir Insights noted that South Korea has strong maritime and industrial capabilities, which are important to the development of offshore wind, and that domestic turbine suppliers are entering the offshore wind market, although they are still behind the rapid turbine upscaling seen in Europe.

“Grid investment is also required,” said Aegir Insights, although the government has indicated that investment is planned in key areas to avoid constraining upcoming projects.

It said the lead times for projects could be affected by a “scattered legislative framework,” with “plenty of permits required” and “differing goals of federal and local authorities.”

Aegir Insights said the risk of delays in the permitting process is greatest during the preparation period, during which a large number of permits and approvals are required from various different authorities.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.