Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Yacht-tech spin-off charts course to more sustainable CTV operations

With offshore wind developers focusing more closely on emissions in their supply chains, a crew transfer vessel designed by a British company has arrived at just the right time

A company with an impeccable pedigree claims a new design it has developed for crew transfer vessels (CTVs) uses less fuel, has lower emissions and is faster and more comfortable for windfarm technicians transported on it. It can also operate in worse conditions than other vessels.

And, as BAR Technologies chief executive John Cooper and chief technology officer Simon Schofield told OWJ in an exclusive interview at the 2020 Offshore Wind Journal Conference in London, the design has already been well received by leading vessel owners, including Seacat Services, and clients contracting for CTVs, including some well-known offshore wind industry leaders.

Led by chairman Martin Whitmarsh, the former McLaren Group team principal and chief executive, who also led development of the Offshore Wind Industry Prospectus commissioned by the Offshore Wind Industry Council, the company believes its design could revolutionise the CTV segment.

BAR Technologies was formed in 2016 to make available a wealth of design knowledge, technical skills and intellectual property developed through involvement in Britain’s attempt to win back the America’s Cup. It draws on the combined experience of a team of naval architects and experts in related disciplines. For the offshore wind industry, the result of this high-level expertise is a new craft that is genuinely innovative, that the company claims can reduce vertical accelerations by 35-70% at the passenger location with operations in 2.5 m significant wave heights, and is between 30% and 50% more fuel efficient than a conventional CTV, depending on operating speed.

That means BAR Technologies’ CTV would be less expensive to operate and has much lower emissions than a conventional design. It also means being able to operate in more challenging sea states with less motion sickness, delivering more operational days, while consuming much less fuel.

BAR Technologies’ design, which has multiple patents, combines a slender monohull with a highly responsive foil optimisation and stabilisation system (FOSS), and a smaller hull known as a small water plane proa outrigger. The company calls it a ‘FOSS SWA Pro Stabilised Monohull.’ The main hull and the outrigger both have the FOSS, which corrects pitch and roll and provides exceptional seakeeping and fuel efficiency.

As Mr Cooper and Mr Schofield explain, the foil stabilisation system has already been adopted and used successfully on Princess Yachts’ R35 motor yacht, which uses an active foil system (AFS) developed in partnership with the company.

On the motor yacht, the AFS works in conjunction with the hull to dramatically improve stability, comfort and seakeeping while reducing drag by up to 30%. Port and starboard foils adjust independently of each other, their positions calculated 100 times per second by an onboard computer.

Foils are not by any means a new feature in the marine industry, but the way the foils BAR Technologies developed works is. The T-shaped, carbon fibre foils the company developed do not lift a vessel out of the water like a hydrofoil, but they do produce additional lift at the stern of the main hull. The really clever part of the process is a control system that adjusts the foils in real-time to take account of the sea state.

The foils adjust the heel angle and attitude of the vessel on which they are installed to ensure the most effective contact area at the bow at any speed, for what Princess Yachts describes as “extreme levels of grip.” On the R35, the AFS “works with the sea rather than battling against it,” the UK-based boatbuilder says.

“On the CTV, together, the slender hullform and outrigger and foils combine to make a fast, stable, seaworthy platform that can also carry cargo,” Mr Cooper tells OWJ. About 10% of the vessel’s displacement is on the outrigger, which is sufficient to enable it to adjust to different cargo and loading states and carry deck cargo equal to that of a 24 m catamaran.

Like the foils on the R35, those on the CTV adjust the heel angle and attitude of the vessel so that less of it is in contact with the water. Resistance is reduced, enabling greater speeds or reducing fuel consumption – and hence emissions – for the same speed.

Mr Schofield says the company estimates the design can provide fuel savings of up to 50% at 15 knots and up to 22% at 30 knots. It is also capable of providing up to a 70% reduction in push-on thrust required compared to a conventional design and has slow speed manoeuvrability equal to that of a 24 m catamaran. Simulations the company has produced demonstrate the innovative design’s manoeuvrability is at least as good as a catamaran, an assertion multiple operators that have been introduced to the design agree with.

BAR Technologies conducted a like-for-like evaluation of the new CTV with a best-in-class catamaran with the same engines and found that it could provide a 600-tonne reduction in CO2 emissions per annum, assuming a vessel working regular, 12-hour shifts.

With a length overall of 30 m, the 24-passenger vessel has a beam of 10.0 m and draft of 1.5 m. The powerplant would take the form of MTU/MAN/Caterpillar engines, providing 2,160 kW for a maximum 31 knots speed and 770 kW at 20 knots.

In the longer term, Mr Cooper expects that BAR Technologies’ new design might have a quite different powertrain to existing designs like catamarans, taking advantage of the efficiencies and redundancy in new forms of propulsion.

Mindful of trends in marine propulsion and of the growing use of new fuels such as hydrogen and hybrids that make use of batteries, the company has not ruled out such an option in due course and describes the design as ‘hybrid ready.’

“We have talked to leading windfarm owners about the usage profile of a CTV and they are open to a variety of solutions. I always ask them to help us lower their emissions by insisting on more efficient boats in their tenders,” Mr Cooper says.

Build cost should not be an issue, either. BAR Technologies has spoken to a number of boatbuilders about the vessel and believes it would as economical to build as a conventional design and its construction cost would approximate to that of a typical 24-m catamaran.

Crewboat also takes advantage of foil technology

Other potential applications of the FOSS concept include larger offshore vessels such as crewboats for the offshore oil and gas sector or larger vessels for windfarms that are further offshore.

With this market in mind, the British company has developed the design of a 50-m crewboat for the Gulf of Mexico, a market that a number of well-known designers and builders have targeted with designs they believe would be more cost-effective than helicopters for crew transfers.

BAR Technologies’ 50-m unit is capable of 45 knots while transferring 40 passengers offshore. Designed to transport passengers in business-style seating, it is capable of transiting in a 3 m significant wave height (Hs) at 35 knots and of conducting transfers in 3 m Hs.

It would be available with options for push-on, ‘Frog’-type basket transfer and walk-to-work capabilities. It can also be configured for DP2 dynamic positioning. The company describes its fuel consumption as “exceptional.” Like the CTV, it is ready for hybrid propulsion, if required.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

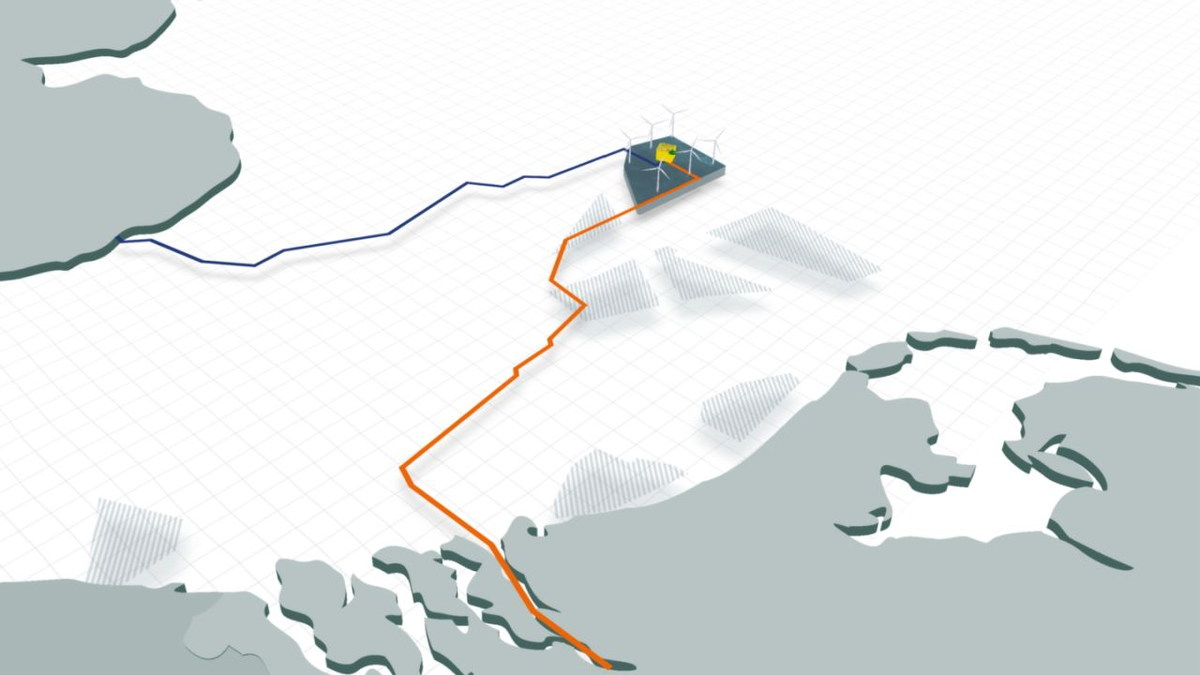

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.