Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Analysis: can China cure its chemical import dependency?

China is the world’s dominant player in liquid chemicals, but will growing domestic production displace imports? asks Maritime Strategies International’s director, Stuart Nicoll

China is the primary supplier of finished goods to the world and as a direct result, is the principal importer of the building blocks for the manufacture of petrochemicals.

From a China Inc/profit maximisation perspective, this reliance on base chemical imports is sub-optimal. The country has limited natural feedstock resources (with the exception of coal) so it could be argued that the ideal outcome would be to import the rawest of raw materials (oil/natural gas/petroleum gases) and retain all the value to the top of the chain (polymers and manufactured goods) within China.

To this end, China has gone through periodic bouts of investment in new chemical capacity over the years, contextualised by the country’s Five Year plans. As a result of these investments, trade in different chemical groups has been heavily impacted. Chinese policy is agnostic to solid, liquid and gaseous compounds and therefore the impact on different shipping sectors has been varied and inconsistent. Nevertheless, the bottom line for the liquid chemical sphere has, overall, been a dramatic rise in imports over the last 15 years.

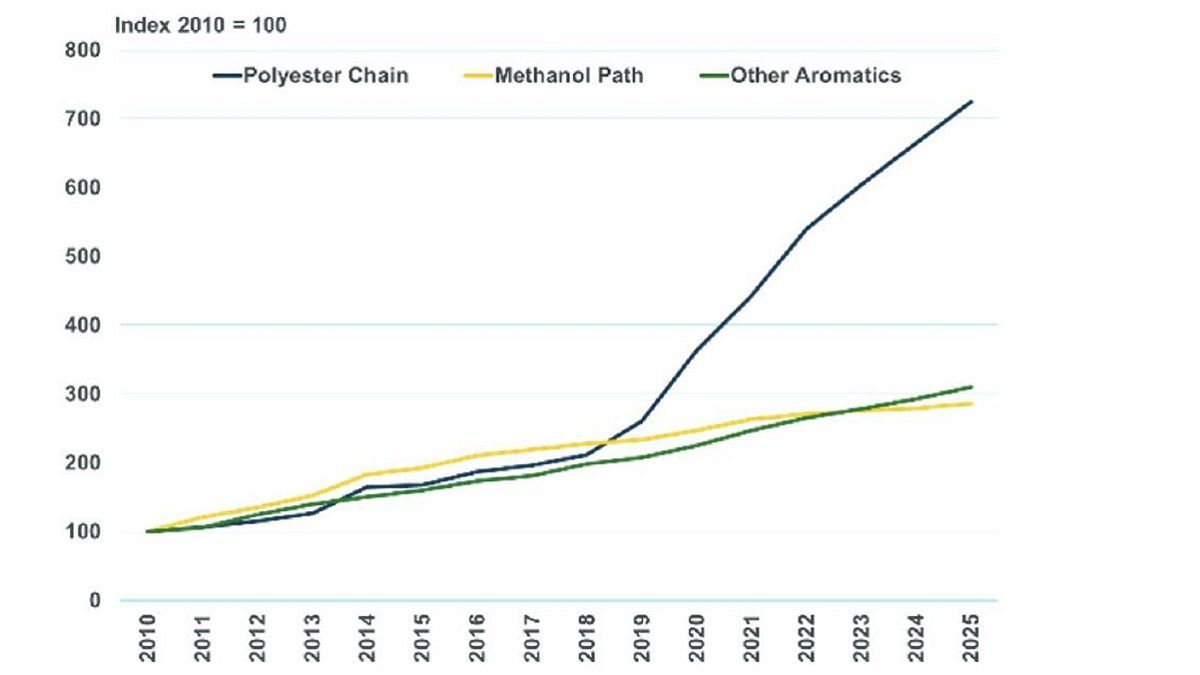

Focusing on liquid chemicals, Chart 1 shows the expansion in production capacity in recent years. Initially, the focus was on methanol (and MTBE, an important derivative) as methanol is a feasible derivative of China’s abundant coal reserves, reducing the inland methanol price by more than 25% when compared to prices for imported material.

However, this policy has not been successful in terms of suppressing imports, as will be discussed below.

Polyester society

The next phase of investment began in 2019 as the focus shifted to the polyester chain. Polyesters are the supercharged chemicals of the current era. Ultimately, and perhaps surprisingly, they tend to end up either in fast fashion or plastic bottles (for this reason, it is now possible to buy clothes made from reconstituted plastic bottles).

Given the underlying chemistry, this has generated a focus within China on paraxylene (also known as PX) and co-feedstock monoethylene glycol, more commonly known as MEG (see Chart 1).

This chart indexes domestic capacity growth in China by key groups. Polyester chain groups the growth in paraxylene and MEG. The methanol path groups the growth in methanol and MTBE. Lastly, ’other aromatics’ groups styrene, benzene and toluene capacity growth.

China has the largest network of polyester plants in the world and the link in the chain between raw material and end product is terephthalic acid (PTA), which is produced by combining PX and MEG. Until the middle of the last decade, China fed its polyester industry with (huge) volumes of PTA imports, which were curtailed by a large influx of new PTA plants. With PTA no longer needed, the focus shifted to imports of paraxylene to feed the PTA facilities. Paraxylene imports soared to 14.3M tonnes in 2020, from 3.5M tonnes in 2010.

Capacity conundrum – domestic or overseas?

The surge in paraxylene imports eventually led to the next obvious step in the chain: Chinese-controlled production of paraxylene. The expansion has taken place on two fronts.

The first was domestic capacity. The surge in new Chinese paraxylene capacity started as recently as 2019, with 4.5M tonnes per annum (tpa) added, followed by a further 9M tpa in 2020. To put that into context, Chinese paraxylene capacity in 2018 (13.6M tpa) lagged that of the rest of northeast Asia by nearly 3M tpa – it is now nearly two-thirds greater.

The doubling of paraxylene capacity within two years is only the start, however, as a further 4M tpa is expected to come online in 2021 and 20.5M tpa between 2022-2025. This remarkable transformation could be expected to cause a collapse in paraxylene imports, but at present the jury is out as most of these new facilities are part of larger complexes that have downstream plants which should consume the output.

To complicate the issue, Chinese companies have also invested in PX capacity in southeast Asia, with Zhejiang Hengyi in Brunei the initial example of this trend. This 1.5M tpa paraxylene complex started in early 2020 and has boosted trade from southeast Asia to China. Other complexes are planned in southeast Asia and will further increase trade to China, most likely at the cost of older plants in northeast Asia.

At present, the paraxylene/PTA policy seems likely to sustain imports to China, though there are clear downside risks if domestic oversupply of PTA leads to production cuts and the surplus PX is then used to displace imports.

In contrast to the plateauing or decline in PX, there will be further strong growth in Chinese imports of MEG. Planned additions of a new wave of capacity will be insufficient to prevent China being short in MEG to feed new polyester plants. For this commodity, the prognosis is a further increase in trade with North America and the Middle East.

Other aromatics – styrene demanded, benzene still short

Apart from paraxylene, the other major traded aromatic organic chemicals are styrene and benzene. In line with the domestic first approach, Chinese styrene imports are expected to continue to decrease in the coming years due to a wave of investment in new styrene capacity. Expansion began in earnest in 2018, when the first large-scale styrene plants were commissioned in China. Given current plans, capacity is expected to reach 22M tpa in 2025, compared to just over 10M tpa in 2018. The rapid increase will exceed demand growth and erode Chinese styrene imports.

While this slew of new styrene capacity in China is bad for trade, it is good news for demand for its precursor benzene. China will continue to be short in benzene in the next five years, even as benzene capacity is set to increase by 38% or 5.5M tpa. Strong growth in benzene derivatives will cause Chinese imports to grow by 87% by 2024.

Methanol paradox

This brings us back to the methanol paradox. As already noted, turning coal into methanol and then olefins seemed an inspired way to utilise the country’s key carbon feedstock, with a strong focus on adding coal to olefins capacity in the last decade. There are issues with the coal to methanol process, however, due to its energy intensity and heavy use of water. Accordingly, we still expect significant imports of methanol.

Another issue is that the abundance of methanol to olefin capacity is in coastal areas, while much of the new methanol capacity added in recent years is in distant inland locations.

Imported seaborne methanol will be key in feeding the former. Chinese methanol imports increased by 2.4M tonnes year-on-year in 2020, primarily from new Iranian facilities. With Iranian plants still not reaching full operations and even more projects coming online in Iran, the US and other regions, methanol trade will be abundant in the forecast. This should drive methanol imports across a number of regions, but mainly in China. MSI forecasts Chinese methanol imports will increase by 4M tonnes (or 30%) in the next five years.

Paradoxical impact – going long

Overall, China remains and will continue to be the most dominant player in liquid chemical imports. Even as trade in some cargoes declines, others will grow causing Chinese organic imports to increase by 5.5M tonnes in the next five years. What will change is the source of the material, to the benefit of tonne-miles and shipping demand.

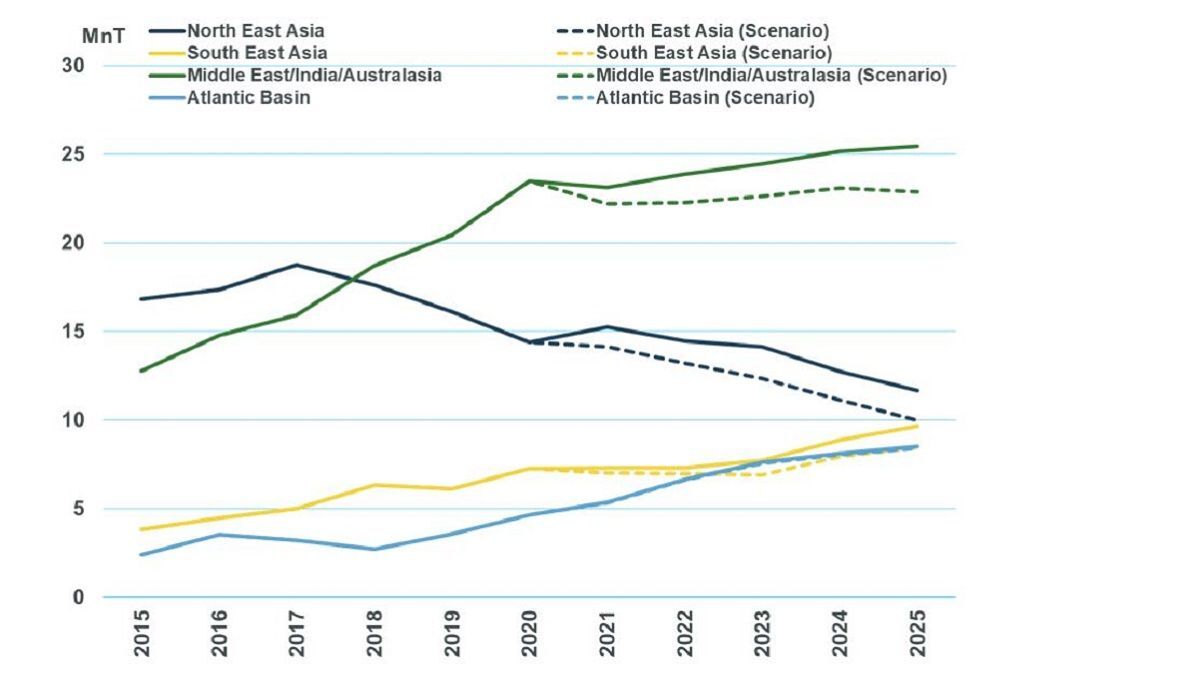

Chart 2 shows our forecast for Chinese organic chemical imports by journey length. Shorthaul trade from northeast Asia has fallen sharply since 2015 and is being replaced by cargoes from further afield. This trend is expected to continue in the forecast.

The chart also explores a downside scenario, investigating the impact if capacity utilisation at Chinese aromatics plants (paraxylene, benzene, styrene) was raised by 5%. In this scenario, there is a marginal aggregate decline in imports by 2025 and northeast Asian exports to China are hit hardest, while trade from the Atlantic Basin is unaffected, as Chinese demand for MEG and methanol will continue to grow.

Translating these changes to ship demand, the impact would be a reduction in required demand of 0.8M dwt. The impact of this reduced demand will be felt across the size spectrum of chemical tankers. The greatest ramifications, in terms of number of vessels impacted, will be the small to medium chemical tankers trading from northeast Asia and southeast Asia to China.

The sizeable fall in imports from the Middle East will affect the 45-55,000-dwt chemical tankers that are mainly used on this route. While owners can reposition their vessels elsewhere, opportunities may be limited given that most incremental longhaul exports are from new chemical capacity already linked to newbuilding orders. For example, US methanol projects have seen investment from chemical tanker owners tied to producers.

In summary, the continued focus on longhaul trade would insulate the overall chemical tanker market from the impact of weaker demand from China. Nevertheless, our scenario would translate into a US$1,000/day reduction in one-year timecharter rates for a 20,000-dwt stainless steel vessel in 2025.

Are you ready for the Annual Offshore Support Journal Conference & Exhibition Tuesday 23 March, 2021. Register here for more details.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.