Business Sectors

Events

Contents

Ever-cheaper renewables could leave Japan with US$71Bn of stranded coal

The steep decline in the cost of renewable energy means the Japanese Government urgently needs to reconsider its pro-coal stance and start investing in wind and utility-scale solar PV

The economic viability of new and existing coal in Japan could be severely undermined by cheap renewables and, without policy reform, could result in massive amounts of stranded assets. This is according to a report from Carbon Tracker, an independent financial think tank that analyses the impact of the energy transition on capital markets and the potential investment in high-cost, carbon-intensive fossil fuels.

The report, Land of the rising sun and offshore wind: the financial risks and economic viability of coal power in Japan, was written in collaboration with the Institute for Future Initiatives at the University of Tokyo and CDP, which runs a global environmental disclosure system. Carbon Tracker analyses the financial and economic viability of new and existing coal power investments in Japan in the report and shines a spotlight on the risks associated with investing and operating coal power in Japan, as the cost of renewable energy such as offshore wind falls.

Carbon Tracker head of power and utilities Matt Gray says, “There’s a technology revolution coursing through the world’s power markets. This revolution is coming to Japan, which means the government urgently needs to reconsider its pro-coal stance.”

CDP Worldwide-Japan director Michiyo Morisawa says, “The current structure is inadequate to cope with climate change and will leave significant debt for future generations. Companies that take urgent action to decarbonise will be the ones who will continue to be successful. Switching away from thermal coal power generation is the default option now.”

As the report notes, Japan’s policymaking is gradually becoming more ambitious with regards to climate change, despite still investing in and supporting coal power.

The recent Strategic Energy Plan stated for the first time in the history of Japan’s energy policy that renewables should become the main source of power and efforts should be made to decarbonise the energy sector by 2050.

In addition, a Long-term Strategy for Decarbonisation, which was approved by the cabinet and submitted to the UNFCCC in June 2019, states “The government will work to reduce CO2 emissions from thermal power generation to realise a decarbonised society consistent with the long-term goals set out in the Paris Agreement.”

However, Carbon Tracker argues that despite these policy signals, Japan is still investing heavily in coal power. The nation currently has over 11 GW of under-construction, permitted or pre-permitted coal capacity as of 20 September 2019. This capacity could have an overnight capital cost of US$29Bn and would need to be closed prematurely to remain consistent with the temperature goal in the Paris Agreement.

“Regardless of the Paris Agreement, there is a growing expectation that coal will face fierce competition from renewable energy in the future,” Carbon Tracker says, “calling into question not only new investment decisions but the long-term viability of the operating fleet.”

Carbon Tracker has developed a project finance model for every planned and under-construction coal unit in Japan. The purpose of the models is to illustrate how, under different scenarios, a coal project could become unviable over its lifetime. In the absence of publicly available information, it developed a breakeven scenario analysis to understand how key variables, such as electricity tariff, coal price or capacity factor, could compromise project viability.

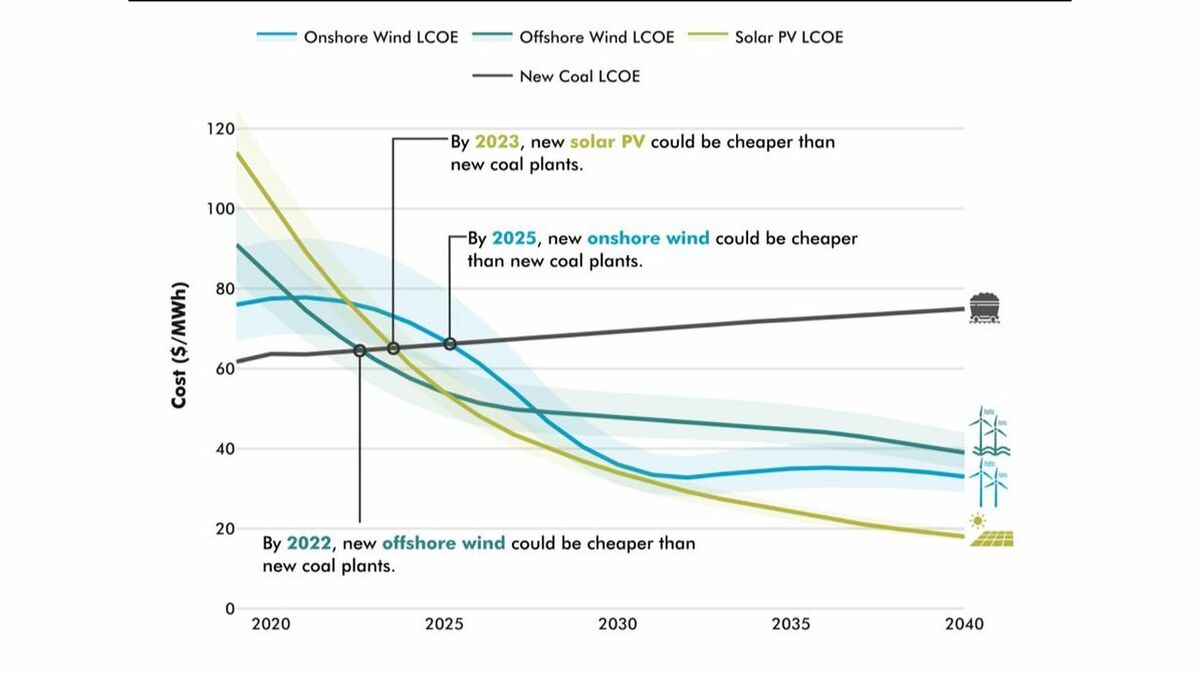

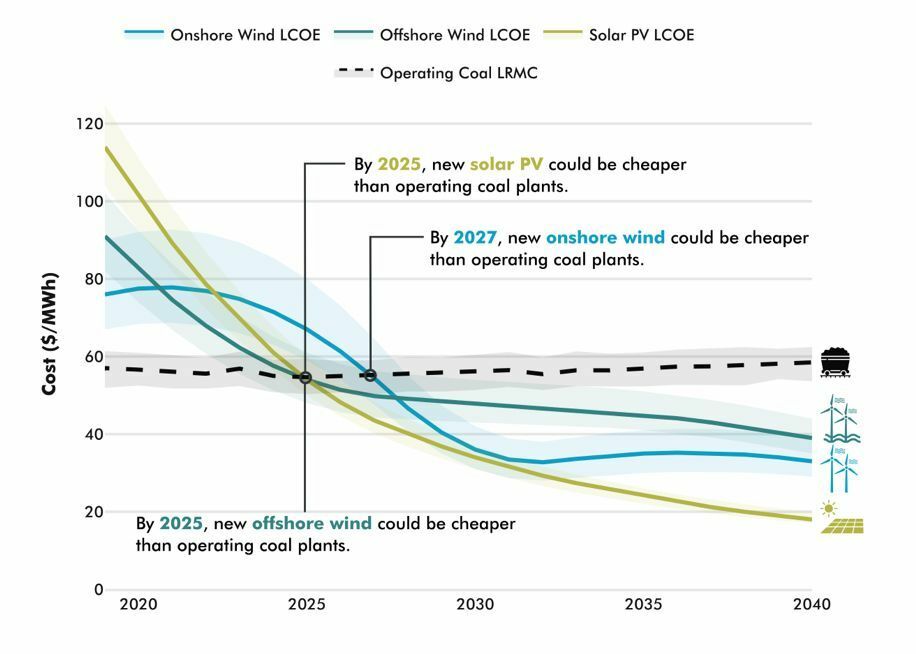

It found that new renewables will be cheaper than new coal by 2022 and existing coal by 2025. Crucially, the levelised cost of energy of offshore wind and utility-scale solar PV could be cheaper than the long-run marginal cost (LRMC) of existing coal plants by 2025 and 2027 for onshore wind.

“There are three economic inflection points which will make coal economically obsolete relative to renewable energy,” says Carbon Tracker. “The first is when new renewable energy outcompetes new or under-construction coal; the second is when new renewable energy outcompetes existing coal; and the third is when new firm (or dispatchable) renewable energy outcompetes existing coal (out of the scope at this stage). Without policy reform, the Japanese consumer could pay for US$71Bn of stranded coal assets through higher power prices.”

Carbon Tracker says its analysis shows that building coal power today “equals high-cost power and fiscal liabilities tomorrow.”

Japan’s planned and operating coal capacity is partially protected by regulations that give coal generators an unfair advantage in the marketplace, but according to Carbon Tracker these regulations are sheltering high-cost coal from significant cost declines in renewable energy.

“Without policy reform, the Japanese consumer may not be receiving the lowest-cost power possible. In our below 2°C scenario, where planned, under-construction and operating coal capacity is forced to shut down in a manner consistent with the temperature goal in the Paris Agreement, stranded asset risk from capital investments and reduced operating cashflows could amount to US$71Bn,” Carbon Tracker says. This scenario is consistent with the government’s ambition to reduce CO2 emissions from thermal power generation consistent with the Paris Agreement.

Carbon Tracker says if Japan intends to meet the temperature goal in the Paris Agreement, it needs to phase-out unabated coal power by 2030. “This reality has immediate implications for new coal investments,” it says. “Both planned and under-construction capacity will unlikely be a least-cost solution over the capital recovery period, which is typically 15-20 years. Our analysis highlights how coal power is losing its economic footing, independent of additional climate change and air pollution policies. As such, Japan should immediately reconsider building new coal.

“Policy makers also need to provide a clear direction of travel for the existing coal fleet that is consistent with the long-term decarbonisation goal of the Paris Agreement. Japanese policymakers should develop a retirement schedule based on the LRMC of individual coal units with a view to inducing a smooth transition from coal. This will allow asset owners to close the higher cost units first and lower cost units last, which should help ensure the end consumer receives the lowest cost power possible.

The report also emphasises the need to accelerate renewable energy through non-discriminatory regulations. “Without further reform the Japanese Government risks missing the economic opportunity associated with renewable energy and locking-in high-cost power,” it says. “In doing so, the government will likely further compromise energy security, public debt and economic competitiveness.

“Renewable energy and other supporting technologies – such as battery storage, demand response and high-voltage transmission – are part of a mega trend with no precedent in the 21st century.

“The benefits from this mega trend will go to those governments who develop a strategy to capture value from the rapid growth of these technologies. Japan has a long track record of technological and engineering prowess that means the nation is well placed to capture value from these technologies as markets mature and product quality commands a price premium. Incentivising renewables begins with seeing these technologies as an opportunity to reinvigorate the nation’s industry and economy as well as promote energy security. To execute this vision, wholesale changes need to be made to ensure renewable capacity gets built at scale and in a manner that maximises its value to the grid. At the heart of these changes is a step change in transparency to avoid discriminatory regulations and potential market abuse.

“Due to the deflationary trend of renewable energy we expect that, in the not too distant future, new investments in renewable energy will likely cost less than running coal. The relative competitiveness of coal-fired power depends on prevailing fuel prices. In the lower bound fuel prices, it could be cheaper to build new offshore wind and solar PV than operate existing coal plants by 2026,” say the authors of the report.

“In the mid-range fuel prices, it could be cheaper to build new offshore wind and solar PV by 2025. Finally, in the upper-bound fuel prices it could be cheaper to build new offshore wind by 2024 and new solar PV by 2025.”

The authors of the report say their analysis is based on a median LCOE forecast for renewables, however, it is plausible that LCOE prices will drop further.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Environmental Protection Webinar Week

Cyber & Vessel Security Webinar Week

The illusion of safety: what we're getting wrong about crews, tech, and fatigue

Responsible Ship Recycling Forum 2025

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.