Business Sectors

Events

Ship Recycling Webinar Week

Contents

Register to read more articles.

How a second-hand ship gave birth to a container giant

From the purchase of one second-hand ship in 1970, the Aponte family-owned MSC has grown to become the world’s largest container shipping group

As Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) crashes through one barrier after another, its rapid expansion inevitably asks questions about what it is up to next in the pursuit of vertical control of the logistics chain on sea, land and air.

So far in 2025 alone, the family-owned maritime giant has become the first container shipping group in the world to operate a fleet of 900 wholly owned, managed or chartered vessels. It has just placed a US$17Bn order for 20 ultra-large container vessels (ULCVs). In July it committed to a five-year, 120-ship programme that will renew its ageing feeder fleet by 2029.

And moving on, such is MSC’s faith in global trade that its current orderbook of ULCVs runs to 74, according to brokers. At this rate, as the group acknowledges, MSC is heading for a 1,000-strong fleet before too long and will in the coming months become the first carrier to break the 7M TEU mark.

This latest spate of records follows a decade of headlong growth that has kept analysts guessing about what the Switzerland-registered giant will do next. After all, in those 10 years the Alponte family-owned group has nearly tripled in size to the point that its fleet alone is worth more than $40Bn, according to VesselsValue. Recently, Swiss newspaper Le Matin put MSC’s overall worth at around $100Bn in what is generally seen as a conservative estimate.

The Aponte family does not try to do everything itself. Along the way it established what it calls “collaborative alliances” — mutually beneficial arrangements with other major lines, including Maersk in the 2M partnership. “This alliance helped MSC enhance its service offerings while maintaining cost efficiency,” said the group.

“MSC is heading for a 1,000-strong fleet”

MSC’s rapid expansion parallels that of rival CMA CGM, the France-based shipping and logistics giant, that in late July declared its interest in acquiring some of the terminals of CK Hutchison in a deal priced at around $22.8Bn. That followed MSC’s apparent withdrawal from exclusive negotiations in a rare abandonment of an acquisition opportunity. Like its Geneva-headquartered competitor, CMA CGM has, over the last few years, invested heavily in the entire logistics chain – ships, containers, terminals, warehouses, e-transport and airlines as it pursues a similar strategy of vertical control. CMA CGM has interests in 65 terminals around the world.

This race is also being run by other big container lines such as Maersk and China’s COSCO, which is involved with CMA CGM in the Ocean Alliance and is mooted as a potential investor in CK Hutchison.

A second-hand ship

MSC was founded in 1970 by sea captain Gianluigi Aponte with one small, second-hand cargo vessel, Patricia, just as containerisation was taking off. In its first years, MSC operated mainly in the Mediterranean and a few ports in Africa. As the group expanded with routes across the Pacific and Atlantic, mainly with second-hand ships, Mr Aponte bet on bigger vessels that reduced the “per-unit cost of shipping and enabled MSC to offer competitive rates,” the company explained. By 1990, its ships were trading all the way to Australia, a far cry from the original short hops to North Africa.

In 1989, MSC invaded the increasingly lucrative cruise business with yet another (extremely) second-hand purchase, Monterey. When MSC bought the much-converted, ex-Matson Line ship and put it under the Star Lauro name, the vessel was already 40 years old. MSC would run it around the Mediterranean for another 15 years before it was sold for scrap. MSC has since grown to become the third largest cruise line in the world.

MSC did not launch its first newbuild, the Fincantieri-built container vessel Alexa, until 1996. In an example of how hard the group works its fleet, the approximately 3,500-TEU vessel is still plying its trade.

The container ship wave

After 40 years as a junior, if growing, operator, in 2010 MSC achieved its first great milestone when it became one of the world’s leading shipping lines.

At the time the group ran about 450 owned and chartered container ships, with a total capacity of about 1.2M TEU. The Alponte family was riding the containerisation wave. As the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad) pointed out in its 2010 review of maritime transport, in that decade the container ship fleet had grown by 154%, three times the rate of the dry and liquid bulk fleet, while general cargo tonnage had hardly moved.

“As vessel sizes continued to increase, the growth rate in TEU capacity was higher, at 5.6%, and the average vessel size went up by 4.7%,” reported Unctad. MSC’s continuing investment in bigger ships was clearly paying off.

At that time the largest container ships, all of them owned by Maersk, could carry about 14,700 containers. In further proof of the correctness of the Alponte family’s strategy, since 1980 the share of containerised tonnage had grown eightfold, while the share of the general cargo fleet had collapsed by half.

As a private company, MSC keeps its finances to itself but it has long been known for ploughing profits back into expansion. For instance, in 2017 MSC bought a minority stake in a much older company, Messina Line. That acquisition opened up short-sea routes within the Mediterranean as well as to Europe and Africa through a fleet of eight roros and container ships with a capacity of a 65,000 TEU.

In 2022, the group achieved another milestone when it overtook Maersk to become the world’s largest container shipping line. At that time, total fleet numbers stood at over 600 vessels. Rated by TEU, the group had more than tripled in size since 2010, while its market share had jumped from about 12% to 17%.

Bigger and bigger

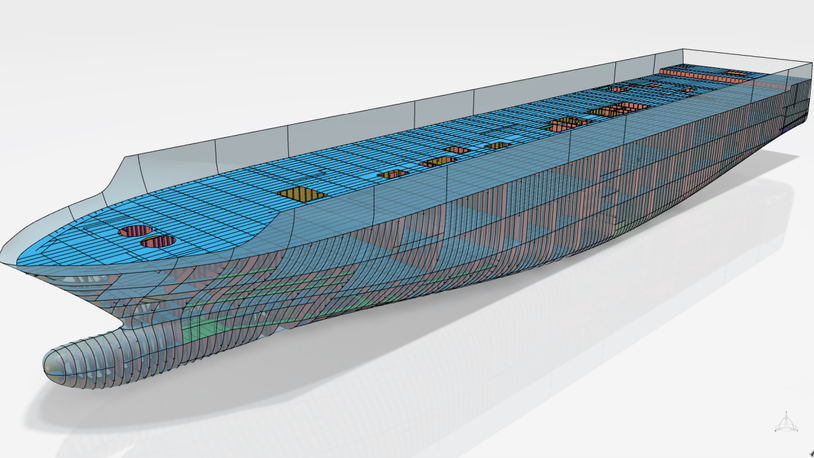

As MSC grew, so did the size of its ships. The Daewoo-built, 2015-launched Oscar broke the 19,000 TEU barrier. That was followed in 2019 by the Samsung-built Gulsun with 23,750 TEU. In March 2023, MSC set two records when the 24,100 TEU Tessa was beaten just three days later by the 24,340-TEU Irina.

MSC is putting its mega-ships of 24,000 TEU on the Africa trade, the first line to do so. Recent arrivals like Diletta and Turkiye are connecting key regions from China and South Korea through Southeast Asia to countries such as Ghana, Togo, Cote d’Ivoire and Cameroon.

MSC chief executive, Soren Toft, who was hired from Maersk in 2020 to look after the global cargo business, is a big believer in West Africa. As he points out, the visit of Diletta to Lome in Togo in April “marks a turning point, ushering in an era of unprecedented shipping capacity for the region.”

In the not so long run, the deployment of some of MSC’s biggest ships on the Asia-West Africa trade may be seen as another far-sighted move. Ports like Kribi in Cameroon have never before seen vessels of 400-m length, 60-m beam and 16-m draught that “represent a new scale for maritime operations in sub-Saharan Africa”, said MSC.

“[The vessels] represent a new scale for maritime operations in sub-Saharan Africa”

It is another vote of faith in the sub-Saharan economy that in late 2022 MSC bought French-owned Bollore Africa Logistics for a reported US$6.57Bn. Since rebranding it Africa Global Logistics (AGL), MSC has promised to do what it is doing in Europe and develop multimodal logistics in rail, road, river and air, as well as shipping, that connect Africa with Asia and Europe. Currently, AGL has 22 port and rail concessions, 66 dry ports and two river terminals.

Dual fuel

Both mega-ships deployed to Africa are dual fuelled. As MSC grows, it is putting its faith in multi-fuelled vessels. China’s Jiangsu New Hantong Ship Heavy Industry is building up to 10 LNG dual-fuelled 21,000-TEU ships, with deliveries scheduled right through to 2028. Consultants, MB Shipbrokers, prices these vessels at around $266M each, excluding the cost of the LNG capability. Brokers report that MSC will take delivery of over 100 dual-fuel newbuilds by 2027.

Meanwhile, other MSC vessels are being adapted to alternative fuels such as LNG as part of its aim to meet IMO’s low-emissions goals. On the cruise side, the new Explora Journeys fleet is in the middle of a six-ship, €3.5Bn expansion. Four of the vessels under construction at Fincantieri’s Sestri Ponente yard will be LNG-fuelled for the time being but will be ready to run on bio and synthetic LNG when they are available in sufficient volumes. Looking further ahead, a large fuel cell may be installed that can convert renewable LNG into hydrogen.

Global ambitions

MSC long ago shed its Mediterranean origins. Around the same time that MSC wrapped up AGL, it also expanded into Latin America, another long-term prospect, through a majority stake in Log-In Logistica, the domestic carrier in Brazil that specialises in coastal routes to the Mercosur economic region. Under MSC ownership the Brazilian carrier has been adding routes including, in early 2025, the re-establishment of a regular service up the Amazon.

In another step with impressive potential, in July 2025 MSC opened its first-ever ship management service in China, where most of its vessels are built. This is in the maritime hub of Jingbo, which handled over a billion tons of cargo in 2024. It is from here that MSC has committed to hire 2,000 Chinese seafarers as early as 2026.

Air and Rail

While the container ships carry less time-sensitive freight, MSC Air Cargo’s five 777s are flying in a partnership with Atlas Air the more urgent and higher-margin products. These are for industries such as automotive, aerospace, pharmaceuticals and perishables. MSC Cargo’s European hub is Liege Airport in France and every indication is that it is growing. Investing in their home country, in mid-2024 the Apontes acquired a 15% stake in Genoa airport.

Simultaneously with air cargo, the group is building strategic links with rail. The first acquisition came in 2015 when it took over the cargo division of a Portuguese operator. Today, under the Medway umbrella for the rail business, MSC runs container trains across the Iberian Peninsula and Belgium and, since 2023, into Italy through other acquisitions; more recently it has delved deeper into France, as part of a long-term strategy of shifting road haulage to rail. By 2027, Medway expects to run a fleet of 115 locomotives, including 27 electric ones.

Another land-based subsidiary, Medlog, is everywhere. Almost continuously it is investing in what it calls “inland logistics platforms” that comprise warehouses, trucks and barges scattered over 80 countries, and rising. And, carrying passengers instead of cargo, in 2024 MSC moved into high-speed trains through a half-share in Italo, a rival to Italy’s state-owned Trenitalia.

A big year

Perhaps MSC’s biggest year for acquisitions came in 2024. In March, its subsidiary group, SAS (Shipping Agencies Services) bought 42% of Lyon-based Clasquin Group, an air and sea forwarding company. In July, Norway’s Gram Car Carriers fell to MSC in a $700M deal. In September, Medlog snapped up British haulier Maritime Transport. In October, Brazil’s 184 year-old Wilson Sons, another port and shipping group, sold a majority stake to MSC. In November, the Port of Hamburg’s main terminal operator, Hamburger Hafen und Logistic, parted with a minority stake to a specially created MSC subsidiary in a difficult and highly political deal involving local authorities. It was a conclusion to a voracious year.

Typically, MSC invests heavily in these acquisitions. For example, in the case of Hamburg it has pledged to provide its share of €450m to equip the port for a target of a million TEU a year by 2031. And starting in 2026, it will build a new German headquarters near the port.

Today’s MSC is hardly recognisable from what it was as recently as 2010. Its shipping line alone sails 300 trade routes and calls at 520 ports. It carries about 24.5m TEU a year. And if the cruise business is included, it employs 200,000 people worldwide.

Hard to credit that it all began with the second-hand Patricia.

Related to this Story

Events

Ship Recycling Webinar Week

International Bulk Shipping Conference 2025

Tankers 2030 Conference

Maritime Navigation Innovation Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.