Business Sectors

Events

Contents

How to structure an LNG-to-power project to mitigate risk

Still evolving, the LNG-to-power market presents emerging opportunities for LNG, but one size does not fit all, and several factors must be considered to mitigate risk, write WFW partners Nick Dingemans and Heike Trischmann

As the world transitions towards a goal of net-zero carbon emissions, LNG will be a key to achieving that target. Natural gas and LNG, especially if they can be blended with hydrogen and (in the future) changed to synthetic gas produced from bio sources, are well placed to support this global transition, not least in power production.

In the last 15 years, the LNG sector has evolved from a traditional point-to-point LNG delivery system to a dynamic market with integrated components and new participants. This change has largely been facilitated by the emergence of floating modular construction for liquefaction and regasification. In addition, a substantial increase in shipping and liquefaction capacity keeps increasing LNG market liquidity. This in turn has allowed new sales models to be created by LNG aggregators and portfolio traders and for them to adjust the global supply/demand profile. The LNG portfolio mix aggregators can offer is also been driven by, and itself keeps driving, different pricing models. While traditional oil indexation remains strong, gas hub pricing linked to NBP, Henry Hub and TTF has emerged as well as spot pricing linked to indices such as JKM and various digital trading platforms such as GLX.

Multiple projects

Although LNG-to-power projects focus on the supply to market, the full value chain comprises various segments that need to be synchronised.

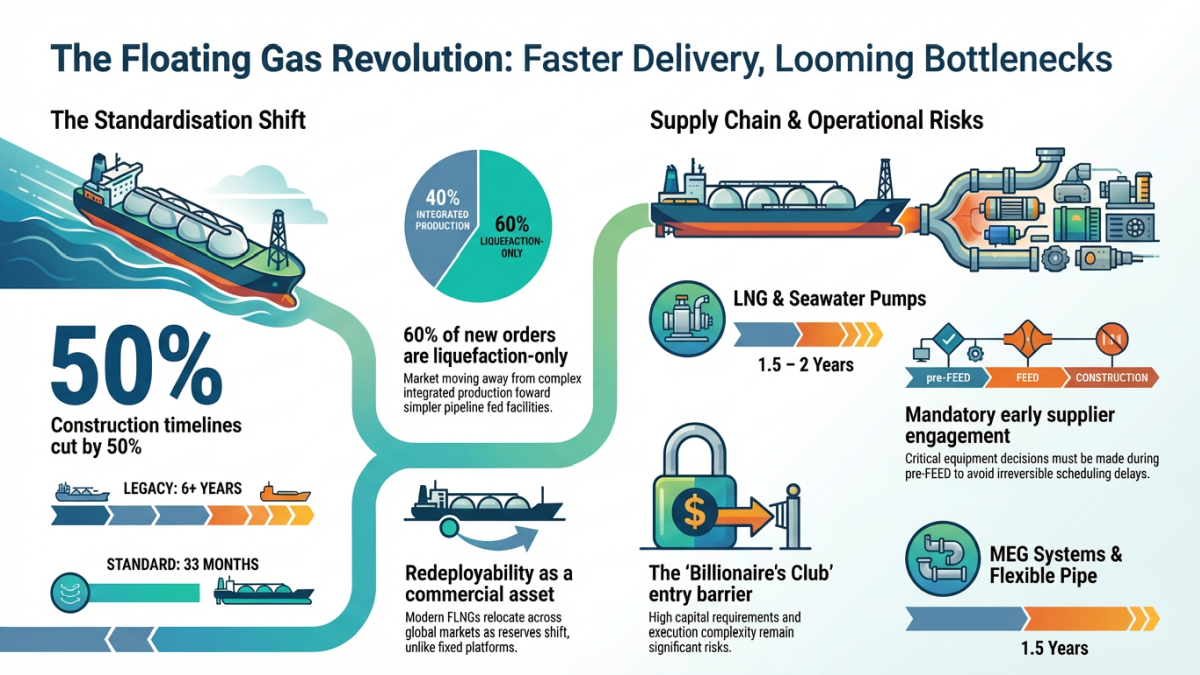

In the upstream segment, development of floating modular construction of vessels and barges in the last 10 years has allowed access to reservoirs which would otherwise have been too small or too far offshore to support their development.

Furthermore, in the midstream, the introduction of the LNG aggregator supply model has produced a more liquid, fungible market. The market has also become deeper and more complex with the addition of portfolio buyers. The availability of floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) and floating storage units (FSUs) has allowed access to new jurisdictions and the gasification of markets where gas has never been an option before.

The downstream segment, ie – the LNG-to-power project itself, is, in many ways, the newest part of the chain and is consequently still evolving in many parts of the world. While the introduction of FSRUs creates infinitely more flexibility, an FSRU being linked to a dedicated power plant creates a more complex matrix of project-on-project risks than traditional models may do.

Therefore, the critical issues that need to be effectively addressed to ensure a successful LNG-to-power project include: mitigation of supply risks for LNG to and regasified LNG within a country; ownership of an FSRU on the one hand and power plant/transmission lines on the other and the co-ordination of their operations; and mitigation of regasified LNG/electricity offtake risks.

The risk matrix created by an LNG-to-power project impacts each part of the downstream segment of the value chain. A solution in one jurisdiction is unlikely to work in precisely the same way in another due to local laws. Structuring, contracting strategies and the available contractual toolbox can be combined in different ways to help mitigate the risk matrix that unfolds in each buyer country.

Corporate structuring

Standalone ownership of each asset in the value chain by a separate project company (that is separate ownership of the FSRU and the power plant) creates complex project-on-project risks but may be necessitated by local law. Local laws, for example, often require the gas asset to be majority held by a monopoly government entity, whereas power assets can be held privately or need to be held by another government monopoly. Such a structure is perhaps the most difficult to manage as it is not always obvious who the best party to manage a particular risk is, and the interests of the different players along the value chain are not necessarily aligned. Given the increased risk of counter party default inherent in this chain of ownership, Lenders are also less comfortable with such structures.

A structuring fix for this is to have cross-ownership between the project companies. Cross-ownership will allow alignment of some of the parties’ interests and can provide a risk-reward motivation for sponsors.

An integrated corporate structure where all sponsors participate in the entire downstream segment is likely to more optimally align interests within the project as it reduces the number of competing positions and, therefore, the risk matrix overall.

These ownership structures are rarely employed in their purest form and the way they are combined will be driven by the risk appetite of sponsors and lenders alike and by any local ownership restriction. Local law advice will, therefore, be key.

Contract structuring

The project-on-project risks created by a particular ownership structure may be further mitigated by using an appropriate contracting strategy.

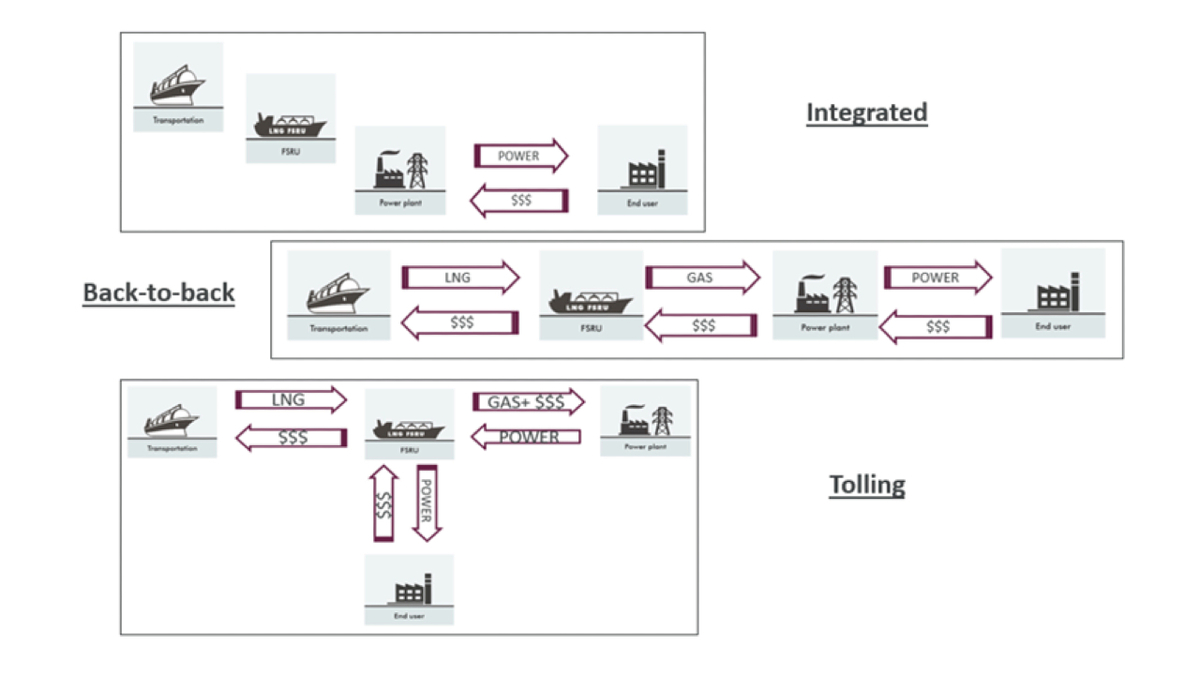

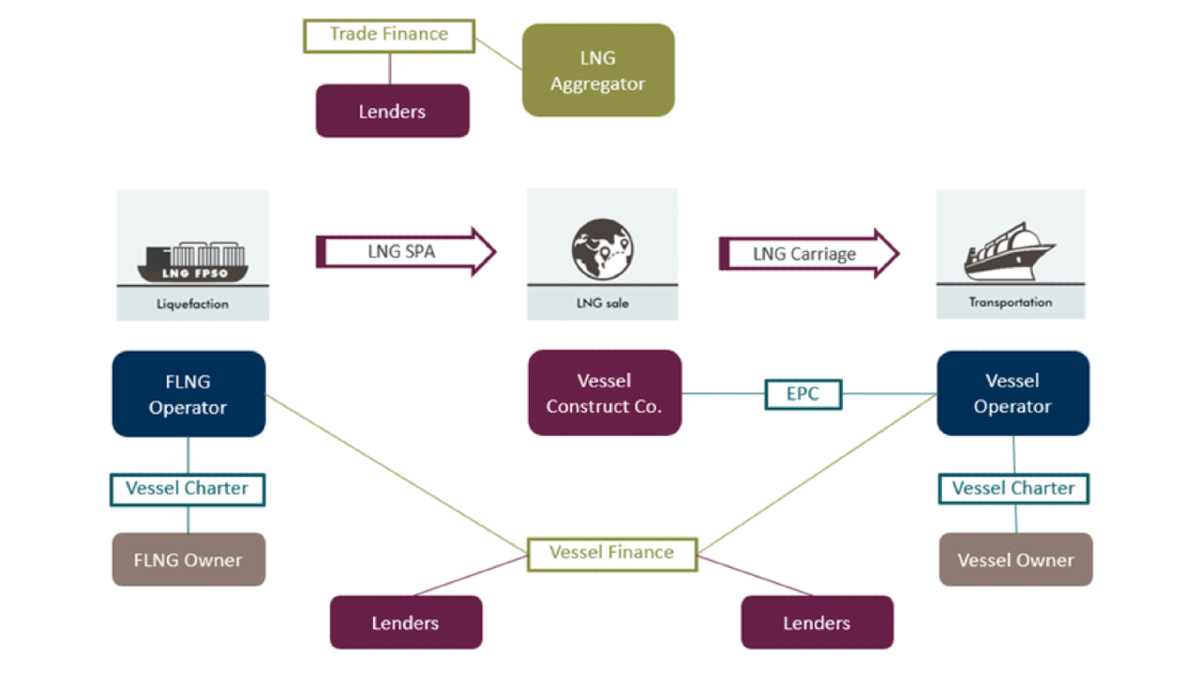

For example, the integrated corporate model often corresponds to an integrated contractual structure where a single company purchases LNG and owns/hires and operates the FSRU and the associated infrastructure, as well as the power plant, and ultimately sells the power. Similar to the corresponding corporate model, from a contractual structuring point of view this represents the simplest model and avoids separate project entities with resulting contractual complexities. However, this model is difficult to finance, particularly in projects fed by a single gas source and selling to a single offtaker. The entire risk will sit with the integrated project company and it must, therefore, be equipped to deal with it effectively. As a result, most integrated projects are being developed either by or in consortium with a gas major who can act as an LNG aggregator and who is also often well versed in electricity production. Gas majors may also be able to circumvent the necessity for project finance by financing the project off their balance sheet.

Where an integrated project is not appropriate, for example because of specific local restrictions, a non-integrated contractual structure may be more appropriate when used with a standalone corporate model. This mandates a gas hub company (HubCo) and an electricity company (IPPCo) to be put in place. Contractually, this could translate into a back-to-back structure, where risks are passed to the entity best placed to deal with them. The ensuing complexity, however, creates multiple counterparty performance risks and this model should, in our view, best be avoided in its purest form.

An alternative option is the more common and easier to manage tolling structure where the LNG buyer tolls it through the FSRU (owned/chartered and operated by HubCo) and then IPPCo takes the power via an energy conversion agreement. Gas can also be sold separately to gas customers. If buyers along the chain are sufficiently creditworthy, a tolling structure will be able to avoid or at least reduce the need for credit support by HubCo and IPPCo.

The imposition of mandatory third-party access by some buyer countries will necessitate access agreements to the FSRU and gas infrastructure with multiple counterparties. These additional complexities create new associated risks of mismatch in relation to LNG scheduling, nominations and, potentially, specification. These risks can be mitigated by introducing an aggregator entity which may have shipping capacity to take cargoes FOB and manage their diversion if necessary. The aggregator could also be a local entity and toll the LNG through the FSRU/gas infrastructure.

As we have seen, the more project companies that are involved in an LNG-to-power project, the higher the contractual complexities and resulting project-on-project risks. While a number of those risks are inherent in complex infrastructure projects of any kind, there are some that are particular to the LNG industry and/or more deeply entrenched in an LNG-to-power project, particularly if developed in emerging markets. Some of these are being looked at in more detail below.

Delays

Unless a delay risk is effectively managed, delays that occur during the construction phase will hamper the start of cash flow being generated and hinder the repayment of project loans. Therefore, start dates, commissioning periods and acceptance tests need to be co-ordinated with each other throughout the in-country contractual chain but also with the start-up of LNG supply; main contractual terms must be passed through as well, if this risk is to be mitigated effectively.

Where the contracts provide for liquidated damages payable upon delay, these should be structured to keep the entire project whole. In capital-intense LNG projects, this may not be possible and the sponsors will look to mitigate a construction phase delay by including in the LNG sales contracts diversion rights and the right to resell the LNG or gas. The best mitigation tool is to ensure the LNG import facilities are in place first, so that the project can start creating some form of revenues and reduce project-on-project risks.

During the operational phase, disruptions due to outages or even a market collapse could occur on both the demand and supply sides. Taking the demand side first, the key contractual tool will be to pass through the main contract terms such as liabilities, force majeure and termination rights, but now contracts also need to deal with passing through maintenance periods and seasonal demand swings. Again, the LNG sales agreement will need diversion rights, but the huge cost outlay and lead times involved in developing LNG projects require volume certainty at the final investment decision (FID) stage. This has traditionally been achieved through locking in long-term take-or-pay obligations. While LNG buyers have agreed to take this volume risk in the past, recent developments resulting in LNG supply outstripping demand have allowed buyers to demand more contractual flexibility.

However, incorporating more flexible terms alters the traditional risk matrix for sellers and, therefore, ultimately lenders. Flexibility will also come at a price and will favour cost-efficient, long-established producers who have perhaps already paid off their project loans. That said, in our view, this degree of flexibility will be difficult to offer/maintain, particularly if and when the market flips again and demand outstrips supply. It may be better, easier or even essential for buyers to mitigate this risk through buying LNG on a portfolio basis either themselves or through an aggregator.

Delays on the supply side can again be mitigated by the buyer conducting its LNG purchase on a portfolio basis. If the supply disruption is in the LNG or gas part of the chain, it will be helpful if the power plant can run on dual fuel. However, in that case, the power plant will likely be required to ensure a minimum gas/LNG offtake. Obviously, the availability of storage will be helpful to cushion supply disruptions and give demand flexibility.

Pricing

LNG pricing formulas were traditionally based on a link to the local fuel competitor that was often regionally entrenched.

The changing dynamics of the LNG market have seen an erosion of the well-tested traditional Atlantic/Asia-Pacific sales and pricing models and introduced greater competition for traditional sellers to those areas. The best example is perhaps the amount of LNG being sold in Asia that is indexed to Henry Hub rather than the traditional JCC (Japanese Crude Cocktail). While the introduction of a price ‘floor’ and ‘ceiling’ are less common these days, clauses that allow parties to review the agreed price formula are now becoming standard and, in some jurisdictions, mandatory due to competition law concerns.

To counteract demand reduction in traditional markets due to an economic slowdown and create new markets for their LNG, aggregators and traders are moving down the value chain and looking to ‘gasify’ new markets. Signs of this activity can clearly be seen in Asia (Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Vietnam) and Latin America (Colombia, Brazil) and we expect the build out of LNG-to-power projects to accelerate especially as countries look to transition away from coal.

This article is an extract from a briefing note, Anatomy of an LNG-to-Power Project. Authors Mr Dingemans and Ms Trischmann can be contacted at www.wfw.com/articles/the-anatomy-of-an-lng-to-power-project/

Ms Trischmann will be one of the high-powered presenters at Riviera’s LNG Ship/Shore Interface, Europe, commencing 19 November. Book your place now

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.