Business Sectors

Events

Contents

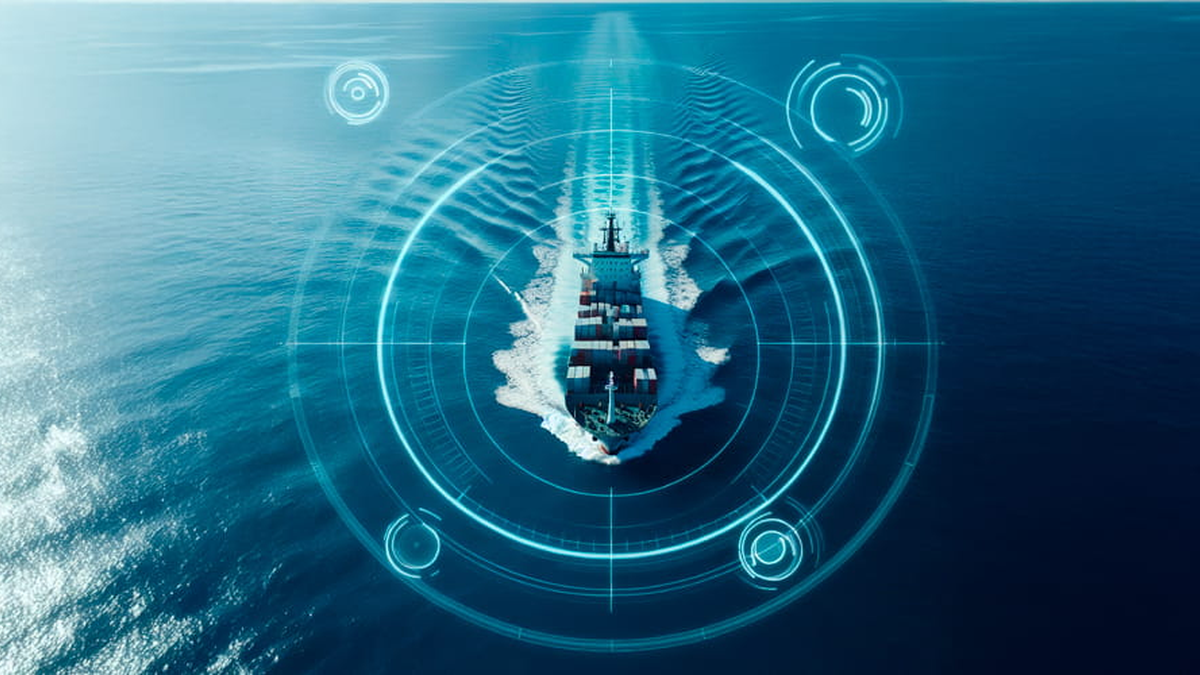

Google takes to the high seas with floating data centres

The leading Internet search provider is examining the concept of offshore floating data centres that could be powered and cooled by the ocean

The leading Internet search provider is examining the concept of offshore floating data centres that could be powered and cooled by the ocean

Following an original application submitted back in 2003, Google has recently filed a patent that details a conceptual sea-based mobile data centre created by stacking containers filled with servers, storage systems and networking gear on barges or other platforms. These offshore centres could sit three to seven miles offshore and reside in approximately 50 to 70m of water.

Perhaps unsurprisingly in this era of alternative energy sources, the search giant has also put forward the idea of powering these ocean data centres with energy gained just from water splashing against the side of the barges.

In its patent application, Google writes: “In general, computing centres are located on a ship or ships, which are then anchored in a water body from which energy from natural motion of the water may be captured, and turned into electricity and/or pumping power for cooling pumps to carry heat away from computers in the data centre.”

The company specifies using Pelamis Wave Energy Converter units to create a wave farm with enough units to create sufficient megawatts to keep its hardware up and running. However, its reliance upon an as yet unproven method of energy production is perhaps the most significant weakness in Google’s plan.

Tidal power certainly shows promise, and there are numerous functional prototypes and development projects worldwide, but to date only a few commercial-scale installations have emerged. A notable example is the SeaGen off the coast of Northern Ireland, which came online earlier this year and fed 150kW into the electrical grid for the first time in July. Once fully functional, SeaGen should provide 1.2MW of power.

Of course, there is nothing to stop Google from deploying an ocean-going data centre powered by conventional fuel sources, but such a vessel would be limited by range and/or fuel capacity. In addition to its own fuel, the data-ship would be forced to carry enough diesel to power its systems. Fuel costs could prove prohibitively expensive, especially if the ship was needed in areas lacking a suitable infrastructure to provide it with a chance to refill both its primary tanks and its generator storage.

The idea of offshore data centres is not necessarily new. A similar plan was mooted by California company, International Data Security, which involved building data centres on decommissioned container ships, but these would be tethered to a pier.

Historically, Google has demonstrated the greatest enthusiasm among the largest service providers in the amount of custom work that it is willing to do on data centre equipment. It is well known that the company builds its own servers and even networking equipment.

Microsoft, however, has recently indicated that it, too, wants to start crafting custom servers for its massive data centres. The software maker is in the midst of building one of the world’s largest such centres near Chicago; this will be comprised of hundreds of standardised shipping containers. It is also reported to be looking into establishing data centres in Russia and Iceland, where power is cheap and abundant and where the colder climate would reduce the energy needed for cooling.

Google’s patent goes on to discuss the potential need for portable data centres of this kind and describes uses that include:

• a temporary need for additional mobile computing power due to a major function or gathering

• the use of a mobile data centre as a primary communications node after a natural disaster, or in any scenario where lines of communication and Internet availability have been compromised

• a means of moving data centres closer to users, decreasing latency, and increasing the number of connections that can be handled simultaneously at certain stress points.

For example, a military presence may be needed in an area, or a natural disaster may bring a need for a computing or telecommunication presence in an area until the natural infrastructure can be repaired or rebuilt. According to Google, such transient events often occur near water.

More cynical analysts, however, have focused on the advanced ‘financial engineering’ of the concept. Locating and building data centres is an expensive business and it is not always easy to secure the necessary (and cheap) electrical power, high-bandwidth data connections, and cooling water. By using renewable energy the centres would be self-sustaining. Deploying pontoons at sea would arguably require less red-tape than setting up on land – and, if floated on international waters, there would be no property taxes to pay.

On the negative side, there would still be costs associated with maintaining a fleet of barges (especially in bad weather or rough seas), in addition to the challenges that would arise regarding server maintenance and security (protection from real pirates?). Notably, the high-speed connections needed to transmit data to and from the centres go largely unmentioned, although subsea cables seem the most likely candidate.

These factors make the effectiveness of Google’s plan highly questionable. That said, the search company seems to believe the hurdles to wave and tidal power generation are close enough to resolution to make the patent worth filing. MEC

Related to this Story

Events

Offshore Support Journal Conference, Americas 2025

LNG Shipping & Terminals Conference 2025

Vessel Optimisation Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.