Business Sectors

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Floating LNG in the Middle East: missed opportunity or the next frontier?

FSRUs and FLNG units are growing globally, but the Middle East lags behind, according to data in the International Gas Union 2025 World LNG Report

Despite having the hydrocarbon reserves, coastline and market proximity that favours floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) development, the Middle East remains on the periphery of a global shift towards offshore LNG infrastructure.

Data presented in the 2025 World LNG Report published by the International Gas Union (IGU) shows a marked absence of floating units in the region’s supply and import portfolios. As floating LNG technologies mature and their global footprint expands, the question arises whether the Gulf’s near-total reliance on onshore infrastructure represents a strategic oversight – or a deliberate choice based on different constraints.

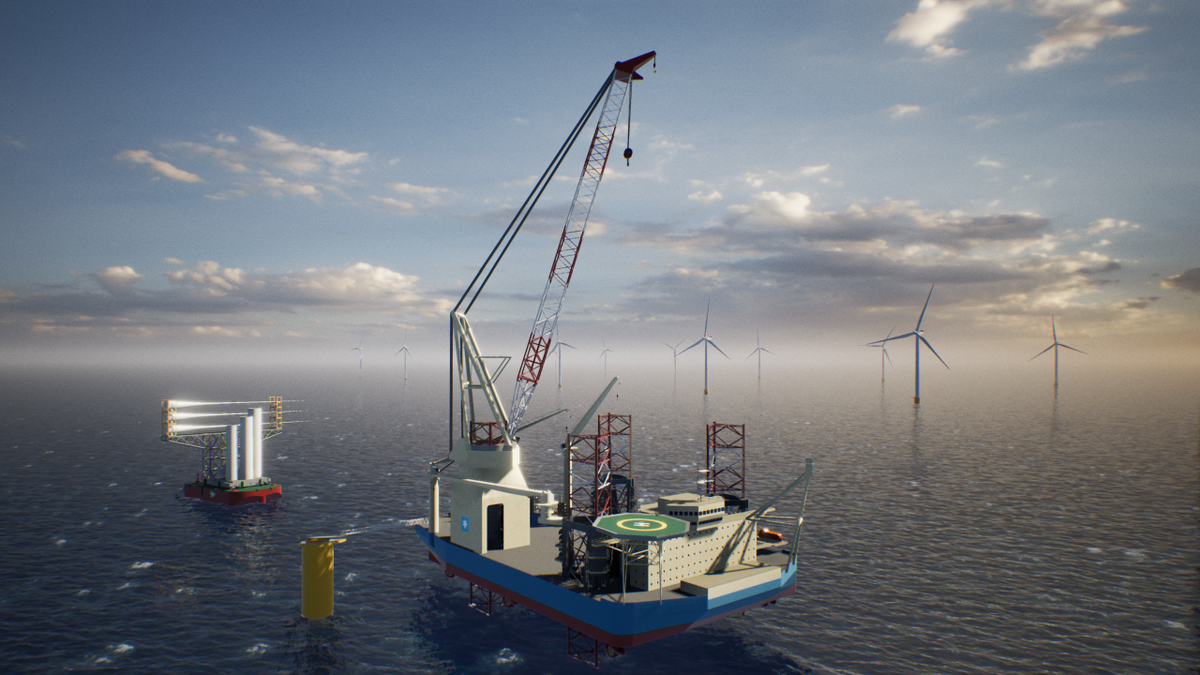

Globally, floating LNG infrastructure – both liquefaction and regasification – is entering a phase of wider standardisation and adoption.

As of the end of 2024, FLNG capacity stood at 14.4M tonnes per annum (mta), up from previous years due to the commissioning of Congo’s Marine XII FLNG and Mexico’s Altamira Fast LNG.

Meanwhile, floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) accounted for 207.3 mta of global capacity across 52 terminals, with eight new floating-based terminals commissioned during the year. These included Para LNG in Brazil, Alexandroupolis in Greece, and new capacity in Germany, all of which reflect the urgency and versatility with which floating solutions are now being deployed.

By contrast, the Middle East has seen no such expansion. The region did not feature among the eight new floating regasification projects in 2024, nor is it listed in the 13 floating terminals currently under construction.

Instead, countries in the Gulf and surrounding region continue to favour fixed onshore liquefaction and regasification terminals, despite a recent push for decarbonisation and efficiency improvements at these facilities.

The absence of floating units is not for lack of available gas.

On the export side, the UAE and Oman are pressing ahead with new projects, including Ruwais LNG and Marsa LNG, respectively – both of which are fully electrified and aim to operate with renewable energy inputs. These facilities, however, are conventional land-based plants.

Qatar, meanwhile, retains the world’s third-largest LNG export volume at 77.2M tonnes in 2024, all through its Ras Laffan onshore complex.

On the import side, Egypt stands out as the only regional example of floating regasification, having reactivated the Ain Sokhna FSRU in June 2024. Even here, however, the reactivation was a return to prior capacity rather than a strategic expansion.

The IGU noted, “FSRUs remain a key solution for new and flexible LNG import capacity,” particularly in markets facing infrastructure bottlenecks or urgent energy needs. Yet this flexibility has not translated into adoption in other Middle Eastern countries, where long-term planning cycles and integrated national energy policies tend to favour onshore investment.

Geopolitical considerations may also play a part and the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait – both critical LNG shipping routes – are routinely subject to naval tension. Floating installations, whether moored offshore or near congested coastal infrastructure, may be perceived as exposed to a greater operational or security risk.

Moreover, sovereign preference for onshore infrastructure may reflect a desire to concentrate LNG value chains within national borders, ensuring revenues, employment and energy security are not dependent on floating assets often owned and managed by foreign entities.

There is also the question of scale. The Middle East’s largest LNG exporters are developing multi-train, high-capacity plants. Floating liquefaction, by contrast, remains more viable for medium-scale operations or marginal fields.

The IGU 2025 report noted, “Standardised second-generation FLNG units” are gaining market traction, particularly for their “shorter lead times and lower capital intensity.”

These characteristics may eventually appeal to Gulf states interested in monetising smaller gas assets or developing LNG capacity in coastal locations where land use is constrained.

Looking ahead, floating LNG could yet find a role in the region’s broader energy strategy.

As the IGU report makes clear, “Floating solutions... are characterised by speedy and highly flexible deployment and lower upfront investment than onshore facilities.”

In a region increasingly focused on energy transition technologies and rapid diversification of gas uses – including bunkering, synthetic methane exports and seasonal imports – the modular nature of floating infrastructure could provide an adaptable option.

Whether this potential translates into action remains to be seen.

Until then, the Middle East remains conspicuous by its absence from the floating LNG revolution.

Sign up for Riviera’s series of technical and operational webinars and conferences:

- Register to attend by visiting our events page.

- Watch recordings from all of our webinars in the webinar library.

Related to this Story

Events

LNG Shipping & Terminals Conference 2025

Vessel Optimisation Webinar Week

Marine Coatings Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.