Business Sectors

Events

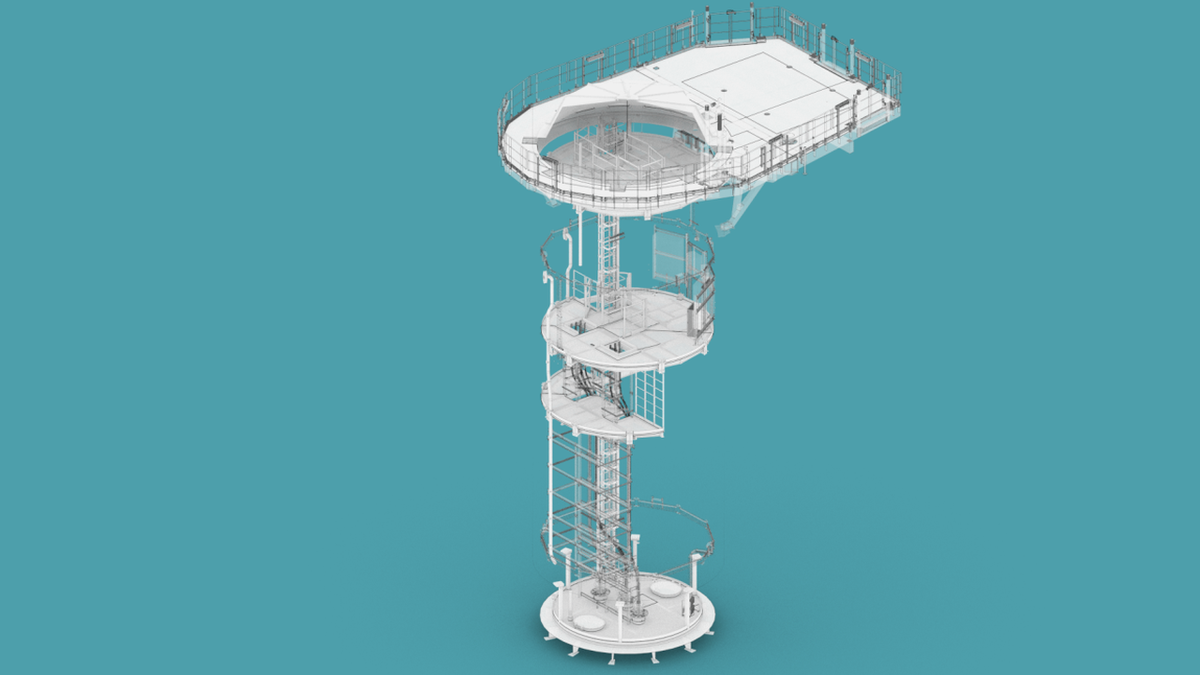

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Salvors want silver-standard ports of refuge

Emergency responders face challenges when towing distressed ships, finding refuge harbours, and dealing with contaminated water, cargo and waste

Salvors’ priorities are the protection of life, vessels, cargo and the environment during the immediate response.

They may need to extinguish fires, refloat grounded ships and consider emergency towage to a safe location.

Once a ship, its crew, any passengers and cargo are safe, then attention turns to finding an available port for dealing with the residual structure, cargo and waste, which can be highly problematic.

Very few ports will accept a casualty, and the corresponding risks and waste. Those that will, either do not have the required infrastructure or are expensive, leading to a need for ‘silver-standard’ ports of refuge – those with sufficient resources to accommodate the casualty, process cargo and recycle waste, but without the expense of the gold standard.

IMO head of legal and external affairs, Dorota Lost-Sieminska, said there is resistance from IMO members to offer a port of refuge to deal with vessel casualties because of the anticipated risk.

She said most IMO members do not have the resources or infrastructure to handle a large casualty and its associated challenges, cargo and waste.

European members

The UK Secretary of State’s representative for maritime salvage and intervention (SOSREP), Stephan Hennig, said the nation has provided ports of refuge in the past for casualties, but there are dangers when towing heavily damaged ships to them, such as issues with structural integrity, cargo damage and instability.

“There are no good outcomes, so it is about controlling the damage and the outcome,” said Mr Hennig.

“We need fast decisions with the information at hand to deal with the accident and work to get the best of bad outcomes.”

Risks to the casualty, responders and any accepting port of refuge are magnified by the increasing size of ships and nature of cargoes, he added.

“We have the authority to take over command and have the right to make the final decision”

For example, lithium batteries generate a higher fire risk and polluting smoke that can be deadly to crew and responders.

In some cases, it is better to extinguish a ship fire offshore and then bring the casualty into port. Before selecting the port, salvors need to know what services are available, the safety factors, and the risks to the port population, said Mr Hennig.

As SOSREP, he makes the ultimate decision on accepting a casualty into a UK port of refuge.

In Germany, the Central Command for Maritime Emergencies (CCME) has the authority to instruct ports to accept distressed ships, as it is responsible for maritime safety in the North Sea, Baltic Sea and over the nation’s exclusive economic zone.

CCME head of maritime emergencies and marine pollution response Tim Fritsche said CCME would interject if a maritime incident is affecting two coastal states, or if it can provide technical support if required.

“We have the authority to take over command and have the right to make the final decision,” he said.

“We can direct a ship to a port of refuge, and port authorities would have to accept this.”

Port of refuge options

A potential port of refuge would need information on the distressed ship before agreeing to accept its arrival.

“A potential port would need to know what is in the cargo and what is on fire,” said D3 Consulting director Martin Bjerregaard.

“Distressed cargo is not waste until it is discarded,” he added. “Then, ports need to find routes for recycling and energy recovery so there is less disposal.”

He said stakeholder engagement and preparation work is needed, which can be challenging and take a lot of time before getting acceptance for refuge.

If a distressed ship requires a port of refuge in the Indian Ocean or southern Atlantic, it could be towed to Jebel Ali in the United Arab Emirates, where the authorities have set up a dedicated harbour for salvage, damaged cargo offloading and waste disposal, but it is costly.

Mr Bjerregaard said Jebel Ali would deal with authorities, agencies and stakeholders to prepare the harbour as a port of refuge.

Brookes Bell director for Europe, Adrian Scales, said Jebel Ali is “a good port of refuge” for dealing with distressed ships. “Jebel Ali is the gold standard, a Rolls-Royce port,” he said.

“There are some other options that cost less, but it would be challenging to get ships to those locations,” Mr Scales added.

“We need a silver standard, a middle ground with enough to cover our requirements but less expensive than the gold standard.”

Three or four ports dedicated to supporting salvage and dealing with distressed ships are needed in strategic locations worldwide.

“Ports should be identified globally for refuge and waste management, and be ready for when there is a casualty,” said Mr Scales.

“They could handle distressed ships and cargo, understand the problems and provide solutions. A port taking a distressed, salvaged ship would benefit financially.

“It would help the local economy and provide a legacy of future income streams. What is a short-term challenge would become a medium-term gain.”

Emergency towage issues

Once a fire is extinguished and the vessel is secured, it will need to be towed to a safe location, which can be challenging.

One issue is that salvors may not know what cargo is on board, especially if the manifest is incorrect or misdeclared.

“A second issue is that fire water may have changed the nature of the cargo, which could create much more waste,” said Mr Scales. This could make it harder to find a port.

Marine Masters owner and director Henk Smith said fire-fighting water and foam could be trapped in internal compartments, such as the engineroom, on a distressed ship, which could impact its stability and cause more waste.

“We need to deal with contaminated water,” he said. “We can decant water from the vessel.” It can be lightered onto a tank barge or tanker in a similar method to removing fuel from a grounded ship.

A salvor then needs to consider “what to do with the cargo, as it needs to get to shore. This can be a nightmare,” said Mr Smith.

Salvors need to deal with the waste and pollutants, depending on the situation and location. “There could be different types of waste,” he said.

“If there is a lot of contaminated water, a salvor may need to hire a tanker to discharge into.”

Then a ship could be ready for its emergency tow to a refuge harbour. But “a longhaul tow may not be practical to a designated port of refuge due to weather, sea conditions and the structure of the ship,” said Mr Smith.

If a ship does get to a port of refuge, and its cargo and waste are discharged, then there could be value for what remains.

“There could be value in the structure for reuse, refurbishment or as an artificial reef; it creates a legacy,” said Mr Smith.

All people quoted in this feature were speaking at the Global Salvage and Wreck Forum that was held in London on 10-11 December 2025

Riviera’s 28th International Tug & Salvage Convention, Exhibition & Awards will be held in Gothenburg, Sweden, in association with Caterpillar, 19-21 May 2026. Use this link for more details of this industry event and the associated social and networking opportunities.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.