Business Sectors

Events

Contents

Register to read more articles.

US, China clash over neutrality of drought-hit Panama Canal

As the Panama Canal recovers from a drought that, as recently as October, threatened to halve the usual number of available slots and has pushed rates sky-high, the vital waterway has also become a geopolitical flashpoint

Behind the scenes, China and the US are involved in a diplomatic and commercial tussle over the neutrality of the canal that the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Professor Daniel Runde, an authority on the issue, sees as increasingly tense.

“With the expansion of Chinese influence in the waterway, the Canal will likely continue to be a point of tension in US-China relations,” he argued in a late-2021 interview.

And little has changed since. More recently, high-ranking US Navy officers are expressing fears that China is using its growing political and commercial influence over the canal and Panama to extend its Belt and Road initiative more deeply into South America.

The US ambassador to Panama, Mari Carmen Aponte, is also concerned at developments. “We do not want to put Panama in a situation where they have to choose between the United States and the People’s Republic of China,” she told Panama TV in early 2023.

Currently, China controls two of Panama’s five principal zone ports through Hong Kong-based Hutchison, with one on each side of the waterway at Balboa and Cristobal. Chinese companies are finishing work on the Amador Pacific Coast cruise terminal. These follow China-based Landbridge buying control of Margarita Island, Panama’s largest port on the Atlantic side, for US$900M in 2016 and China Communications Construction’s building of a deepwater port.

And according to US trade publication Engineering News-Record, a consortium of Chinese state-owned firms will soon restart construction of a fourth US$1.3Bn bridge across the Canal after at least five years of disputes.

Like other Chinese-initiated projects, the contract for the fourth bridge was signed by Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela who had, at Beijing’s behest, repudiated Panama’s recognition of Taiwan as a separate country. As Engineering News-Record reports, “Having already ended Panama’s relationship with Taiwan and establishing official diplomatic ties with Beijing in 2017, President Varela made deals with other Chinese companies to build a US$4Bn high-speed rail line connecting Panama City with Costa Rica, US$1Bn in port facilities, an electrical transmission project, convention centre and other facilities.”

Projects dropped

However, many of these projects were dropped or modified after Mr Varela was ousted by current President Laurentino Cortizo. “His policies have been more favourable to US interests,” notes the magazine. Also, a little-known flying visit to Panama City by former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo helped force a rethink.

But China is already well entrenched in the canal. Numerous Chinese companies including Huawei have set up regional distribution hubs in the Panama Pacific free trade zone and at least four Chinese banks have licences in Panama.

Land bridge status

Bigger than all these though would be a land bridge – a ’dry channel’ – that would provide an alternative to the Panama Canal, according to the Chinese and Colombian governments that are championing the project. According to Colombian President Gustavo Petro, also an economist, the project is “very advanced”. If it happens (and there are many sceptics), the land bridge would connect the port of Buenaventura with the Atlantic by a rail link.

Most of China’s inroads into the Canal happened under the noses of the Trump administration, and the Biden White House has been trying to unravel those it can, given the economic importance to the US of the waterway that it ceded to Panama in 1999 on condition it remained politically neutral “with fair access to all nations and non-discriminatory tolls”.

Vital link for US container traffic

As the IMF points out, “In fiscal year 2021, the United States was the origin or destination of 72.5% of all ships crossing the canal. China came in second, with 22.1% of the traffic being ships from China. Japan followed closely with 14.7%.” In normal times about 1,000 ships pass through the 64 km-long canal each month carrying some 40M tonnes of goods.

The canal is vital link to US cargo, accounting for about 40% of US container traffic annually. And the drought conditions at the canal have also forced some container shipping lines to seek a land-based alternative for moving their cargo.

In an advisory to its clients on 12 January, box shipping giant Maersk said it was shifting container cargo transiting from Australia and New Zealand to the US East Coast that would normally pass through the canal to the Panama Canal Railway “to safeguard its customers’ supply chains”.

Relief ahead?

It looks as though the problems posed to shipping by the drought-affected canal — and exacerbated by the attacks on vessels in the Red Sea — may be easing. In mid-December the rains finally began to fall on Gatun Lake, a major source of water for the locks, following the driest October on record for the canal’s watershed.

As the lake began to fill, the canal authority felt able to increase the number of daily transits to 24 from January, up from the limit of 18 it was going to impose from February and two more than through December. Although 24 a day is about 12 less than the usual number, it is an important improvement that will be welcomed by operators as an alternative to sailing round the Cape of Good Hope.

Some shipping is affected more than others. According to the canal authority, the dry bulk and LNG sectors are the hardest-hit by the transit limits while container ships are the least-affected because up to 70% of those using the canal can handle a maximum draught of 13.4 m.

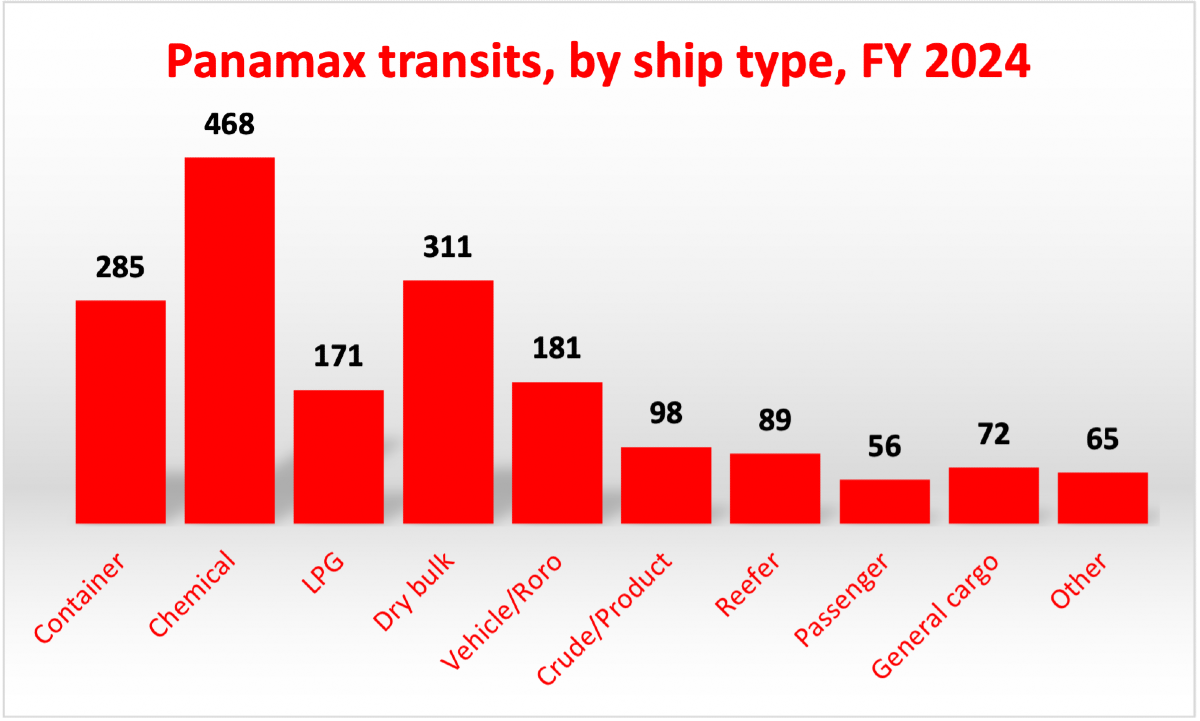

Container ships have accounted for 285 or 15.9% of the Panamax transits, and 425 or 57.8% of the neoPanamax transits during the three months of fiscal year 2024, according to Panama Canal Authority data.

Saving water

As the lake ran dry, the canal authority imposed a series of water-saving and operational measures. The introduction of draught restrictions means neoPanamax vessels were allowed maximum draughts of up to 13.4 m. A technique called cross-filling meant water could be sent from one lock chamber to another, a strategy that saved the equivalent consumption of six daily transits. Tandem lockages meant that two ships could share one chamber provided the size of the vessels allowed it. And among other measures the authority tightened up on water leaks in valves and gates.

“In the neoPanamax locks the direction and scheduling of transits are analysed to make the most of every drop of this resource,” summarises the authority, citing water savings of as much as 50%.

However, although the authority has done all it can, trade routes will suffer for months to come, predicts PortWatch, a new open platform launched by the IMF and University of Oxford. “Ports in Panama, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Peru, El Salvador and Jamaica are suffering most from these delays, with 10-25% of their total maritime trade flows affected.”

Sign up for Riviera’s series of technical and operational webinars and conferences:

- Register to attend by visiting our events page.

- Watch recordings from all of our webinars in the webinar library.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Environmental Protection Webinar Week

Cyber & Vessel Security Webinar Week

The illusion of safety: what we're getting wrong about crews, tech, and fatigue

Responsible Ship Recycling Forum 2025

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.