Business Sectors

Events

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Overlap between offshore wind and oil and gas licences: a problem or an opportunity?

Licence awards announced by the UK North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) in May 2024 have aroused concern in the offshore wind industry, but might provide opportunities too

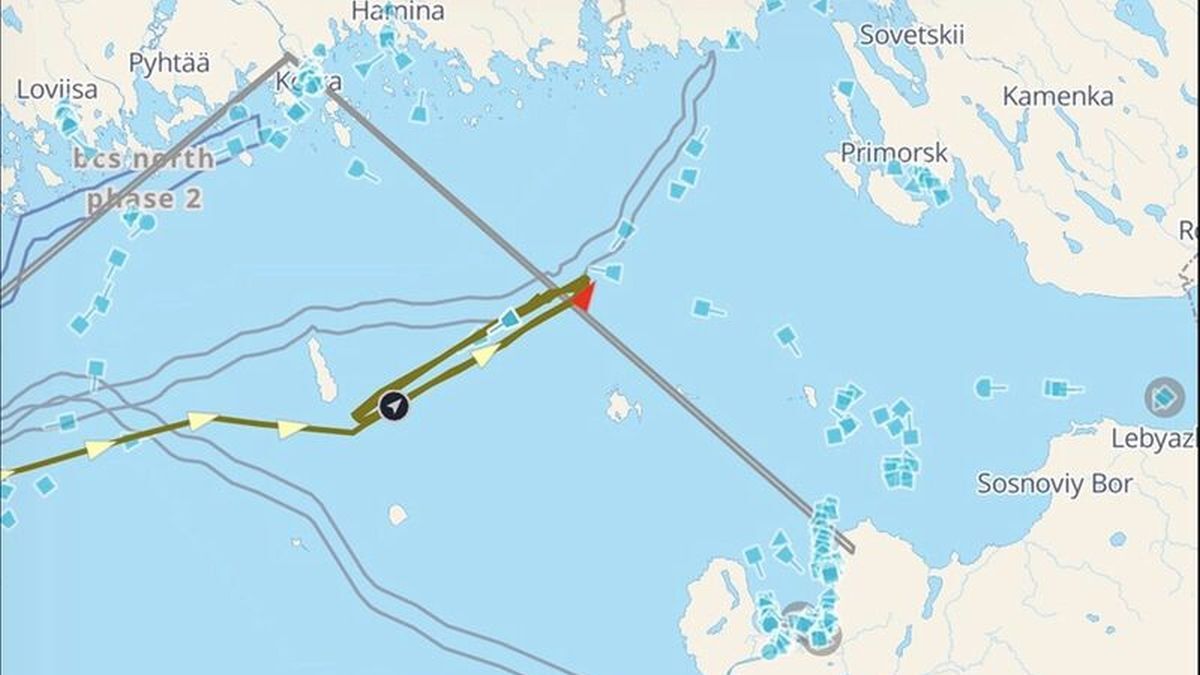

On 3 May 2024, the NSTA offered 29 new oil and gas licence awards in Tranche 3 of its 33rd licensing round. For the first time, some of the newly licensed blocks within these award areas overlap with currently existing UK offshore wind leases. Xodus has identified 17 areas where Tranche 3 provisional awards could share space with seabed that was originally leased for offshore wind development.

The news generated a flurry of statements issued by industry trade bodies, environmental campaign groups, and parliamentary politicians alike. Depending on who you turn to for perspective, you’ll get opinions that are either 180 degrees from each other, or so carefully worded that they barely give away an opinion at all.

Depending on which industry you typically immerse yourself in, the implications of the Tranche 3 licences may be unclear. So, in the name of, ‘Yes, but how, specifically, could this be either amazing or a disaster?’ let’s get into it.

For me, this is offshore wind, but the offshore wind supply chain, which is what I study day-to-day, has a fair amount of crossover with offshore oil and gas.

The TL;DR version is that the NSTA’s Tranche 3 licence offers could lead to opportunities for oil and gas electrification and emissions reduction; and more revenue streams for windfarms. But there are wider risks for the wind industry when it comes to environmental impact assessments (EIAs); supply chain competition; and project cost increases.

The long read version is as follows. When the NSTA offers an initial term oil and gas licence, this typically gives the licensee the right to explore for petroleum only. Geophysical, geotechnical and seismic data-gathering (Phases A and B) and exploratory well drilling (Phase C) have to take place first, to confirm there is indeed oil and gas present within the licensed area.

The licensees’ Field Development Plans and subsequent development consent applications are separate processes that take place later. Each Field Development Plan must propose a Field Determination Area. Once agreed upon, the Field Determination Area ultimately limits the boundaries of the new oil and gas field. This is kind of (emphasis on ‘kind of’) similar to how an offshore windfarm can have a more limited footprint, compared to its seabed lease award boundaries. Some of the Tranche 3 licences the NSTA issued are on a faster timeline, though, and this is likely due to the maturity of their respective locations.

While most of the provisional awards are Phase A and B data-gathering licences, two awards are already at Phase C, meaning the licensees could, in theory, soon start drilling exploratory wells within their respective blocks to confirm if there’s oil and gas present. Furthermore, four of the Tranche 3 awards have been granted ‘Straight to Second Term’ status, which indicates a right to obtain Development & Production consents, including the submission of a Field Development Plan. ‘Straight to Second Term’ is a status the NSTA can grant for an existing discovery or for the redevelopment of an oil and gas field.

None of the ‘Straight to Second Term’ licenses overlap with any existing offshore wind lease areas. However, four blocks located within the two Phase C licence areas do.

Three of these Phase C blocks overlap Dogger Bank South West, while the other one overlaps Outer Dowsing. Dogger Bank South West has an estimated start-up date of 2030; Outer Dowsing’s start-up is estimated for 2031. The remaining 15 offshore wind areas on our list now share seabed with newly issued Phase A and B licenses. Of these: five host operating windfarms; two have windfarms under construction; and five have consented projects due to start up between 2028 and 2030.

Progress on these windfarms is far enough along that clashes posed by potential field development plans and determination areas could be addressed early on and limited. Seismic surveying works for oil and gas could be disrupted by windfarm piling and offshore construction activities taking place near these blocks. But again, closer co-ordination between the affected parties could probably address this.

However, our final three overlapping Phase A/B areas – Cenos, Dogger Bank South East, and MarramWind – have environmental scoping opinions issued, but their developers have not yet applied for consents. The estimated start-up dates for these three projects fall between 2031 and 2034. There may be greater potential for clashes within these three areas, as well as the Phase C areas, which are also at preconsent stages.

The EIA process for these five windfarms could be affected by the much shorter development timelines envisioned for the newly licensed oil and gas blocks. Developers will have to take increased oil and gas activities into consideration during their EIA processes, which can take 3-4 years to complete.

Marine licences often require in-combination impacts to be noted before any plans are approved; this is particularly the case in some special areas of conservation. The affected parties with rights to these areas will need to begin dialogue early to mitigate this particular risk.

Given that Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) sees potential for the Tranche 3 areas to come onstream within the next five years – or by 2029 – there’s a chance that up to 29 new oil and gas assets could be added to the UK’s energy mix before several GW of previously planned offshore wind capacity can start operating. It can take 10 years, on average, to develop an offshore windfarm once its seabed exclusivity is awarded. Some of these overlapping windfarm areas were only just awarded exclusivity in 2023.

The NSTA says one of its aims with the 33rd Licensing Round is to get newly licensed areas into production as quickly as possible. OEUK analysis suggests that 180 UK oil and gas fields are due to cease production by 2030. Should no new oil and gas developments come online between now and then to plug the gap, OEUK argues this could make the UK overly reliant on importing oil and gas to meet energy demand – not an ideal position to be in when it comes to the UK’s energy security and cost-of-living crisis.

To be fair to the NSTA, fast production is just one aim of these Tranche 3 licences. After consulting with The Crown Estate and Crown Estate Scotland, the NSTA added a commercial clause specific to any licences overlapping offshore wind areas; this clause requires the respective oil and gas licence holders to negotiate in good faith with the respective offshore wind developers before any oil and gas activity takes place. Oil and gas companies will need to agree with windfarm developers on how to proceed before any exploratory drilling can actually begin. If engagement takes place early enough, this could potentially lead to beneficial arrangements for both parties.

The NSTA also states that May 2024’s provisional awards are designed to comply with the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero’s (DESNZ) Climate Compatibility Checkpoint and the revised Oil & Gas Authority (OGA) Strategy. The OGA Strategy requires the industry to operate in a way that’s consistent with net-zero ambitions. The Checkpoint, meanwhile, has a target of 50% reduction in oil and gas asset emissions from 2018 levels by 2030. Further targets aim for a 90% reduction by 2040 and 100% reduction by 2050. The main strategy DESNZ has identified for emissions reduction is oil and gas asset electrification.

Could this lead to wind turbines located within the overlapping Tranche 3 areas powering any potential oil and gas assets built nearby? It’s possible, and perhaps this was some of the thinking behind allowing new oil and gas assets to be located so close to current and future offshore wind projects. After all, Norway did exactly this with the Hywind Tampen project and Scotland encouraged this approach through last year’s Targeted Oil and Gas round (the ‘TOG’ in ‘INTOG’). Any new field development plans emerging from the Tranche 3 process will likely need to demonstrate their assets can be fully electrified and integrate with future technologies. This could include being able to receive electricity from nearby offshore windfarms.

But there may be more practical and feasible ways to achieve asset electrification than using offshore wind turbines. Depending on where any future oil and gas assets are located, tiebacks to fully electrified existing platforms or cable connections to shore may be a better option. And depending on the development timelines for each, a Tranche 3 asset could be in production up to five years before a nearby offshore windfarm begins operating. This could limit the incentive for Tranche 3 licensees to work with offshore wind lease holders on establishing asset electrification with wind turbines unless early engagement between the affected stakeholders can be established and design considerations prioritised.

Furthermore, if these new NSTA awards do lead to several new assets beginning production within the next five years – regardless of their proximity to offshore windfarms – this could lead to oil and gas field developments getting to shared parts of the offshore energy supply chain first. Competition for vessels, fabrication yards, moorings, engineering services, surveying and EIA services could get pretty steep.

If oil and gas developers snap up limited supply chain capacity, this could add to the cost risks and inflationary pressure that offshore wind developers are already dealing with. That could make future Contract for Difference (CfD) and zero-subsidy approaches untenable in the UK – something we’ve already observed with the AR5 CfD round in 2023.

While there’s a chance that some future offshore wind capacity could be sold to a Tranche 3 project, this option won’t be available to every windfarm that’s currently in development. While 8.9 GW of preconsented offshore windfarms overlap the Tranche 3 licence awards, another 50 GW of preconsented capacity is located nowhere near them. And a sudden increase to supply chain competition could affect it all.

Too large an increase to offshore wind project capex could increase the risk of GW-scale offshore wind projects being delayed or even cancelled, which is not an ideal position to be in, when it comes to the UK’s energy transition and the climate crisis.

Faster oil and gas production against slower (or possibly cancelled) offshore wind developments could undermine the UK achieving its climate targets, which have already been walked back by respective Westminster and Scottish governments. The UK is trying to improve its energy security by increasing both oil and gas and offshore wind output at the same time. But the approaches are currently in conflict with one another.

This latest tranche of NSTA licensing places the tension between oil and gas and offshore wind centre stage. As a result, stakeholders will need to begin addressing the points of overlap and potential conflicts in a more co-ordinated and earnest fashion. And the earlier this can be done, the better.

*Genevieve Wheeler Melvin is principal consultant, Xodus Renewables Industry Development. Xodus is a global energy consultancy providing support across the energy spectrum, from advisory services to supply chain advice

Related to this Story

Events

Offshore Support Journal Conference, Americas 2025

LNG Shipping & Terminals Conference 2025

Vessel Optimisation Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.