Business Sectors

Events

Offshore Support Journal Conference, Middle East 2025

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Hull coatings for decarbonisation: solutions, challenges, and next steps

Experts examine hull coatings as a decarbonisation and compliance lever, showing how selection, validation and data-led maintenance impacts EU ETS and CII exposure

Marine coatings have shifted from a niche efficiency topic to a core compliance lever as fuel, carbon and port‑state risks have tightened simultaneously.

This was the one of the findings of the Jotun-sponsored webinar “Hull coatings for decarbonisation: current solutions, compliance challenges, and next steps” held on 27 October 2025.

The webinar featured Jotun’s global category manager, hull performance, Habibe Escobar, Navigator Gas head of marine projects, Carsten Manniche, Hempel’s head of global business development, Nikolaj Malmberg, and Jotun’s global category manager, hull performance Jon Magnus Skaret.

In the webinar, Mr Skaret’s noted that a complex regulatory landscape would “push innovations” in underwater coatings and that suppliers had to help owners navigate choices to remain compliant.

Ms Escobar underlined during the webinar that regulation was now a “ticket to play”, and the differentiator was understanding “what is right for that particular vessel or fleet”.

Mr Malmberg said that coatings remained a “low‑hanging fruit” for decarbonising the existing fleet, with external validations critical to wider adoption.

Mr Manniche summed up the operator position: reduce friction decisively, instrument the fleet to measure effects, plan for cleaning and durability trade‑offs, and bring charterers into the carbon‑cost discussion with verifiable data.

“Low friction is a good starting point, but it does not equal hydrodynamic performance”

Speakers during the webinar emphasised three operator imperatives: integrate coating choice into dry‑dock planning; produce audit‑ready evidence of hull performance; and schedule maintenance using operational data as regimes hardened through 2027.

Why this mattered was set out plainly by Ms Escobar: “The main concept is achieving a clean hull. Because if you have a clean hull, then you will be able to reduce your fuel consumption and cut carbon emissions,” she said, adding that a clean hull also lowered the risk of transferring invasive species.

Ms Escobar noted that overlapping regimes such as EU ETS and FuelEU Maritime made choices complex for owners and operators.

Jotun’s presentations reinforced the point: biofouling raised friction, slowed ships and lifted fuel burn; protecting hulls from fouling could, in aggregate, reduce shipping’s CO2 emissions “by as much as 19%”, aligning operational gains with biodiversity goals.

The challenge was not only scientific but commercial and Ms Escobar reported a survey of 1,000 owners and operators in which about 40% had incurred biofouling‑related regulatory penalties, with similar numbers refused entry to ports; half now avoided ports where rejection was likely.

One in five respondents knew the solution on their hull was not efficient enough.

Her conclusion was that performance shortfalls often arose from a mismatch between coating choice and the vessel’s trading pattern, rather than any single technology failing, and that the industry needed to “bridge the gap” with better selection and monitoring.

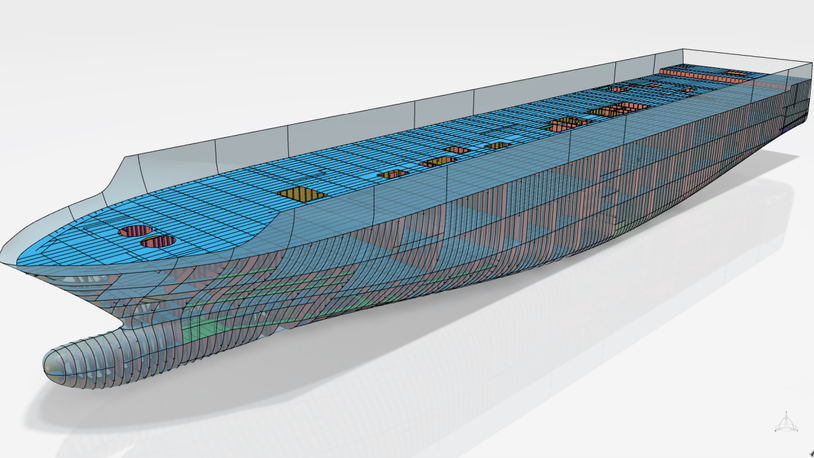

Navigator Gas provided a detailed operator case study. Mr Manniche explained the company instrumented its gas carriers with high‑frequency sensors, including mass‑flow, torsion and power meters, plus draught, speed, wind and other inputs, to robustly measure coating effects.

Testing silicone‑based antifoulings on sister ships created a clean comparison and, “after less than a year”, the owner changed strategy and “decided to go full blown on silicone”, despite the need to manage softness near locks and when docking alongside berths.

Over a full five‑year docking cycle the firm observed strong performance from the silicone coating for roughly three‑and‑a‑half years, before a decline that might require cleaning; averaged across trades and seasons the company saw “a benefit of at least 10-12%”, especially valuable where Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) engine‑power limits capped available speed margins.

Solutions for hull coatings for decarbonisation fell into three strands: selecting the right coating for the trade; validating performance claims; and embedding data‑led in‑service management.

Actual hydrodynamic performance depended on the operating profile — speeds, idle days, port routines and market volatility — and on how a coating interacted with the boundary layer around the hull in real water, not just its nominal smoothness.

“Low friction is a good starting point, but it does not equal hydrodynamic performance,” said Mr Skaret.

Jotun’s prescription was “tailored to trade”: combine an operational understanding of where and how the vessel would work with a commercial view of future uncertainty (lay‑ups, recharters, acquired ships with existing systems), then select for in‑service and out‑of‑dock performance, backed by proactive monitoring and, where needed, guarantees.

DNV independently validated Hempel’s claims and found a 6% efficiency gain compared with top-tier self-polishing antifouling coatings, with a speed loss of 1.4% over time. He also pointed to RightShip guidance recognising low-friction coatings in vessel-efficiency ratings.; Hempel reported more than 30 vessels with verified greenhouse‑gas rating upgrades after coating changes.

Mr Skaret said proactive monitoring of fouling risk and speed loss was essential, using vessel and open‑source data to trigger inspections or cleaning before performance degraded.

Ms Escobar added that Jotun’s HullKeeper platform linked trade‑driven fouling risk to speed deviation and achieved “close to 80% accuracy” when its predictions were checked against physical condition, allowing operators to act early, especially when vessels switched from predictable liner trades to volatile spot markets.

Jotun summarised the approach as “intelligent hull condition management”, emphasising continuous risk tracking across the docking cycle.

“The economics were shifting further in favour of premium systems as carbon costs rose”

Compliance and cost ran through the discussion and it was highlighted that coating selection and documentation were increasingly scrutinised by IMO instruments, such as CII, which scored how much CO2 a ship emitted per unit of transport work, and by EU ETS, which priced a portion of voyages touching European ports.

Owners therefore needed audit‑ready evidence of hull performance, integrated into dry‑dock plans and maintenance budgets, and should expect coating choice to feature in charterparty conversations. Mr Malmberg argued that the economics were shifting further in favour of premium systems as carbon costs rose and rating frameworks integrated hull friction explicitly.

The webinar audience probed practical limits in the question‑and‑answer session, and Mr Manniche advised protecting areas prone to mechanical damage in case of higher frequency port calls with a harder belt above the waterline to mitigate scuffing, even if it slightly reduced frictional benefit.

He cautioned that cleaning silicone surfaces was “not necessarily easy”, so methods had to be planned with suppliers, and he noted that some yards or jurisdictions restricted certain silicon-based products.

On modelling return on investment for slow vessels (for example, offshore support or dredging units), both coating manufacturers said the business case depended strongly on activity level and idle days; high‑activity ships recovered investment faster, but low‑activity vessels could still justify upgrades where port‑state requirements or carbon costs were material.

A recurring concern from the webinar audience was whether compliance rhetoric was crowding out performance reality.

Mr Manniche’s response was direct: discussions with charterers were “way beyond technical”, now including who benefited from EU allowances; however, he said, “We first need to demonstrate that we can measure” and agree baselines before sharing value.

Related to this Story

Events

Offshore Support Journal Conference, Middle East 2025

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Maritime Decarbonization Conference, Americas 2026

Offshore Wind Journal Conference 2026

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.