Business Sectors

Events

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Winds of change blow in the North Sea

A DNV report forecasts a six-fold expansion of offshore wind in the North Sea, requiring collaborative marine spatial planning and investment in ports and vessels

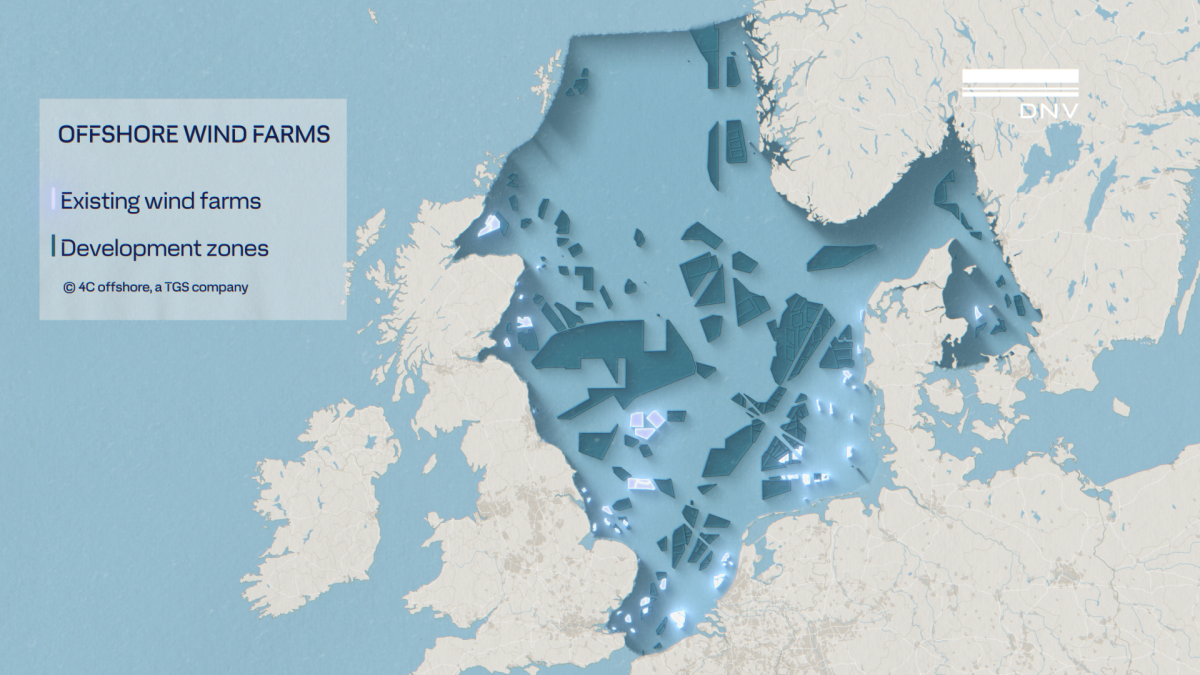

Over the next 25 years, the global energy transition will reshape the North Sea, with offshore wind growing six-fold, producing as much energy as offshore oil and gas in the region by 2050. But this enormous expansion will occupy a large footprint — about 9% of the sea basin area in the North Sea — putting the sector in competition for space with the aquaculture and offshore oil and gas industries, according to a report by a leading class society.

Offshore wind is forecast to reach 214 GW, on par with offshore oil and gas production, with floating wind accounting for about 27 GW, according to DNV’s report, North Sea Forecast: Ocean’s Future to 2050. The class society says growth of offshore wind will create spatial planning challenges for the region that will require strong collaboration between countries and sectors. This collaboration will underpin the diversification of the North Sea to meet government objectives and climate change policies for renewable energy, CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions reductions, and sustainable seafood production.

“The North Sea faces substantial decommissioning activity”

For this expansion to succeed, the offshore wind industry will have to overcome “bottlenecks in the supply chains” and build “close collaboration among offshore wind developers, electricity transmission system operators, ports, shipowners, and original equipment manufacturers,” says the report.

DNV forecasts offshore wind will require more than 60,000 km2 of area in the North Sea by 2050. Much of this development will occur in shallow water (50 m or less) and near shore (50 km or less). This could be problematic for the aquaculture industry.

“The North Sea is central to Europe’s energy, food and supply chain security,” said DNV director of food and ocean systems, Bente Pretlove. “Collaboration across borders and sectors is required to enhance security in the North Sea and to overcome challenges such as ocean health, spatial competition and infrastructure for the offshore wind sector,” she said.

Bottle necks ahead

Surprisingly, the phenomenal growth of offshore wind will not be “sufficient to meet the green energy ambitions of the Ostend Declaration for the North Sea,” says DNV. Among the maritime bottlenecks will be North Sea ports and specialised windfarm vessels. The report suggests the capacity of port facilities dedicated to offshore wind construction will need to be quadrupled, and more wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) and heavy-lift vessels are required to install and service the wind turbines.

Complicating the picture are the ever-increasing sizes of wind turbines and heights of towers, which drive the requirements for new WTIVs.

“Without increasing standardisation of turbine designs, WTIVs will have to be designed with additional margins and prepare for larger retrofits to accommodate changing installation operations,” says DNV.

Service operation vessels equipped with motion compensated gangways provide accommodation and extend the weather window for maintenance operations offshore. For offshore windfarms near shore, crew transfer vessels provide sufficient access and are used extensively in O&M.

Offshore oil and gas

The rise of renewables will coincide with a fall in offshore oil and gas production. DNV estimates the North Sea’s oil production will decrease to 800,000 barrels per day in 2050, less than a fifth of today’s production. While DNV notes gas will have “more staying power due to its strategic importance to Europe,” its production will fall, too. It is forecast to fall to 60Bn cubic metres per day, almost two-thirds less than in 2024.

The North Sea is an important source of food, and the report forecasts it will retain current catch volumes due to an increased demand for seafood and good management practices.

“Gas will have more staying power”

Five of the world’s 10 leading maritime cities are situated on the North Sea which gives the region the infrastructure, financial power and expertise to deal with the challenges. However, there is a lack of policy standardisation, which makes sustainable growth difficult. The EU’s policies relating to marine spatial planning differs to that of both Norway and the UK. As of today, only a few countries can claim to have integrated ecosystem-based management into their spatial planning.

DNV director offshore classification, Torgeir Sterri, says the North Sea’s “evolving landscape demands closer co-ordination across borders and sectors. For the offshore industry, this means adapting to a more integrated approach to regulation, spatial planning, and technology. Our mission is to support stakeholders in navigating this complexity and ensure safe operations while facilitating the transition to new energy systems,” he adds.

The North Sea faces substantial decommissioning activity, as both offshore oil and gas structures and offshore wind turbines will reach the end of their service lives.

The OSPAR convention regulates decommissioning activities for the North Atlantic and requires restoration of the seabed. This limits the opportunity for operators to abandon marine structures, for instance by allowing them to remain in place as artificial reefs. Costs of decommissioning are often very high, and there will likely be a high demand for vessels that can perform decommissioning operations.

Carbon capture

An emerging sector in the North Sea is carbon capture and storage (CCS). Depleted offshore oil and gas reservoirs offer opportunities for reuse as CCS facilities. Northern Lights, the world’s first cross-border commercial carbon transport and storage facility, was commissioned in 2024.

Located in Øygarden, near Bergen, the Northern Lights facility is backed by a joint venture partnership between Equinor, TotalEnergies and Shell, and is part of the Longship full-scale CCS project initiated by the Norwegian government. In March, the trio took FID to progress phase two of the Northern Lights development. The decision was made after inking a deal with Stockholm Exergi to transport and store up to 900,000 tonnes of biogenic CO2 annually for 15 years.

Related to this Story

Events

Offshore Support Journal Conference, Americas 2025

LNG Shipping & Terminals Conference 2025

Vessel Optimisation Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.