Business Sectors

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Norway’s nuclear-powered commercial ship project pushes ahead

The NuProShip project targets a ‘workable prototype’, but regulatory and safety uncertainties and technology complexities will slow the uptake of nuclear power

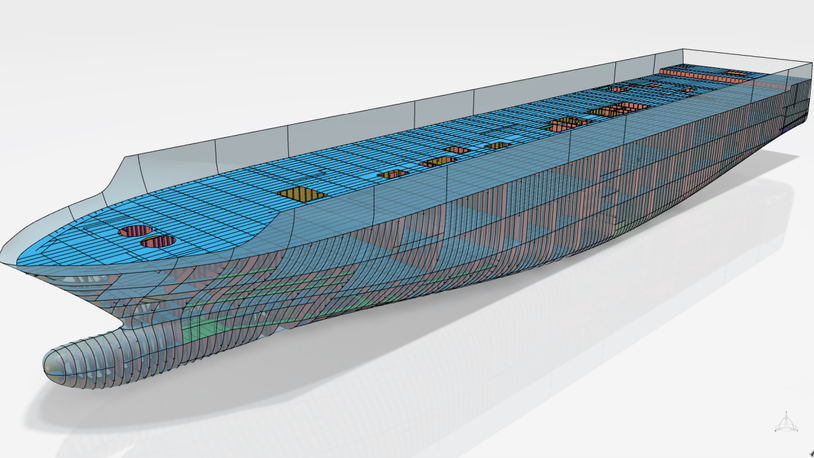

Norway’s project to develop nuclear-powered merchant ships moved into its second phase in January with the target being the development of a workable prototype – probably a tanker – based on the latest 25 to 55 MW fourth-generation reactors.

The NuProShip consortium’s work advances amid mounting excitement about the role of nuclear propulsion in the greening of the commercial fleet. Although the regulatory hurdles are daunting, class society Lloyd’s Register (LR) pointed out in mid-2024: “Nuclear power could transform the maritime industry with emissions-free shipping, whilst extending the lifecycle of vessels and removing the uncertainty of fuel and refuelling infrastructure development. But regulation and safety considerations must be addressed for its widespread commercial adoption.”

That is certainly the thinking of government-owned China State Shipbuilding Corp, which announced in late 2023 that it would build a giant thorium reactor-drive container vessel. And in the last 12 months other moves have been made to put reactors in commercial ships.

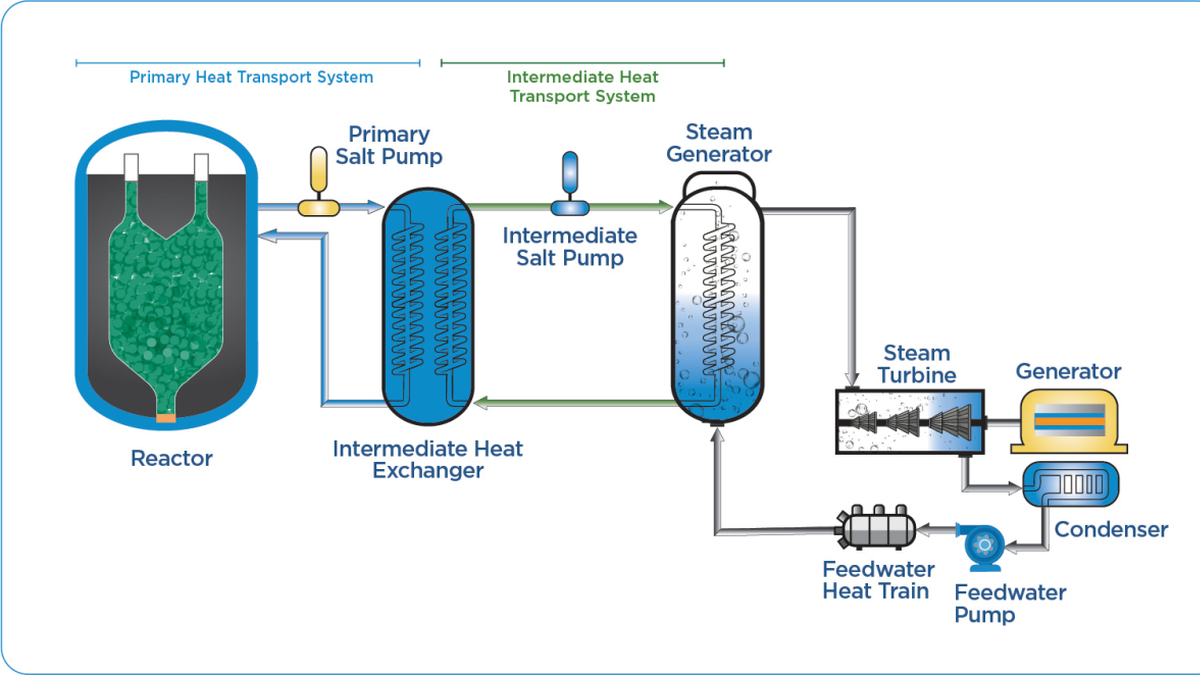

Meantime, having evaluated no less than 99 companies working on advanced reactor technologies during the first phase of the NuProShip project, the partners are moving forward with three reactor types – Kairos Power’s fluoride high-temperature molten salt reactor using TRISO fuel particles; Ultrasafe’s helium-cooled gas reactor, also employing TRISO fuel particles; and Blykalla’s lead-cooled reactor concept utilising uranium oxide as fuel. The first two companies are American and the third Swedish.

“This is a critical step for evaluating the business viability of nuclear technology”

In NuProShip 2 the existing consortium, comprising Vard, DNV, Norwegian Maritime Administration, Knutsen Tankers and IDOM - the Spanish nuclear consultancy - will be joined by insurance companies, the views of which will be vital. “[This] is a critical step for evaluating the business viability of nuclear technology in the shipping industry,” explain the partners.

This second phase is a two-year project, while a third phase will involve testing the prototype. The target date for a nuclear-powered ship is 2030. The Research Council of Norway is providing the funds and the project manager is Professor Jan Emblemsvag, an advocate of nuclear power who, in 2024, said he believes it is the prime solution for the production of the massive volumes of clean energy needed for hydrogen-based e-fuels.

Small modular reactors

NuProShip 1 has already made a lot of progress. Although the main task was to “adjust a fourth-generation small modular reactor (SMR) to the needs of international shipping”, according to the consortium, the studies also took in a multitude of related issues such as regulation, safety, ship design, maintenance, handling of radioactive material and the work of the crew.

If nuclear-powered shipping happens, it will be based on SMRs, according to current thinking. They have a power capacity of up to 300 MW per unit, roughly a third of the capacity of traditional nuclear reactors, but that is considered to be quite enough. “[These reactors] represent a leap forward in design, emphasising safety, efficiency, and modularity for streamlined production,” considers LR. “As SMR technology matures and regulatory clarity increases, ship designs optimised for nuclear propulsion will emerge, ushering in a new era of efficient and environmentally friendly vessels.”

Dr Mamdouh el-Shanawany, chair of the Nuclear Energy Maritime Organisation (NEMO), would agree. He wrote in the introduction to LR’s Fuel for Thought in mid-2024, “nuclear power is the ultimate decarbonisation solution, but won’t be suitable for all ships”. And citing the “unparalleled safety record” over the last 70 years of nuclear-driven navy ships, icebreakers and a few state-owned cargo vessels, he believes the advanced technologies currently under development “will be suitable for safe deployment on a new generation of large, efficient cargo ships that can sail at higher speeds with zero emissions.”

Banks back nuclear

Momentum is certainly building for this latest generation of reactors. For the first time, in September 2024 during New York Climate Week, 14 large banks and financial institutions pledged to support the COP28 target of tripling the capacity of nuclear energy. Simultaneously, investment in nuclear energy projects has suddenly spiked, up from an annual average of US$30Bn during the early years of the last decade to US$50Bn a year between 2017 and 2023, according to Atlantic Council, the geopolitical think tank.

Uncertainties and complexities

That is way short of the US$150Bn a year that some experts believe is required by 2050 and, as LR explains, despite the latest commitments investors are still reluctant to come to the party “due to the uncertainties around the wider uptake of nuclear technology in commercial shipping.”

According to LR, the wider adoption of nuclear propulsion will change the way shipowners manage power. Instead of controlling their own propulsion, which has historically been the case, “the commercial relationships between shipowners and energy producers will be altered as power is likely to be leased from reactor owners, separating the shipowner from the complexities of licensing and operating nuclear technology.”

“These reactors represent a leap forward in design”

In short, nuclear propulsion will be too complex for shipowners to handle by themselves.

And some believe it is too risky in a period of geopolitical tension. American scientist, George Moore, who worked for the International Atomic Energy Agency, sounded a warning in late 2024. Writing in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, he argued that the current enthusiasm “ignores nuclear safety and security concerns that make the development of nuclear-powered commercial ships a particularly bad idea in an era of international terrorism and piracy. And that’s not even to mention the cost of insuring them.”

Security and insurance aside, the challenges he cites are hostile public attitudes and doubtful economics, including the “expensive security measures needed for operations to be considered reasonably safe from terrorist attacks” as well as the, albeit low, potential for a reactor accident.

Dr Moore also sees much heavier responsibilities being put on the shoulders of regulators: “The agencies will need to expand their risk analysis methodology to include unique sea-going risks, and they should be empowered to block construction if the risks are found to exceed acceptable levels.”

So clearly, a long way to go yet.

Related to this Story

Events

International Bulk Shipping Conference 2025

Tankers 2030 Conference

Maritime Navigation Innovation Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.