Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Regulations chase the coming wave of remote-controlled vessels

Four zero-emissions ferries for Norway are among the autonomous and remote-controlled maritime projects that are outpacing the current regulatory framework

As construction begins on Fjord1’s new fleet of double-ended, zero-emissions autonomous ferries, shipping organisations are scrambling to draw up regulations to keep pace with a steady flow of projects for remotely-controlled vessels.

Due for delivery in 2026, the ferries will operate on the northwest coast of Norway on the 20-minute, 5.6-km Larvik-Oppedal crossing.

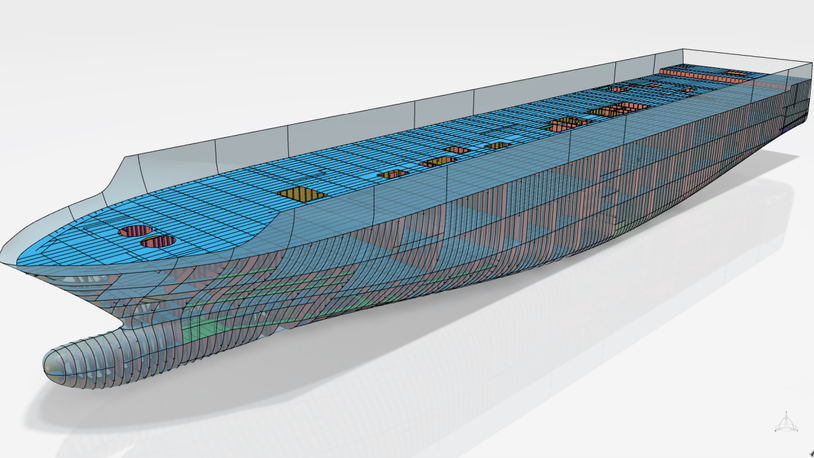

Being built by Turkey’s Tersan Shipyard, the Norwegian ferry owner’s 120-m, electric-powered ferries are just one of several autonomous-focused initiatives underway to make remote-controlled shipping a reality. The maritime industry is pushing autonomous and remote-control functions beyond subsea vessels to applications in passenger, military, survey and hydrographic ships. Although most, but not all, of these are currently ‘lean-crewed’, in the future they will be unmanned, as the latest research indicates.

“Remotely controlled ships are operating commercially in several parts of the world,” notes Capt Ajay Hazari, who led the drafting team which, in early October, drew up BIMCO’s Autoshipman, a standard contractual foundation for third-party ship managers to deliver services for the operation of remotely-controlled or fully autonomous vessels. “We are seeing growth in this sector, with several companies emerging and offering remote control management services to shipowners,” he notes.

This is clearly just a start. Until now, points out BIMCO, “remotely controlled ships [have been] used primarily in inland waterways and coastal trade, but the sector is growing.”

Autoshipman is based on Shipman, which governs all the multiple obligations, responsibilities and liabilities. A dense document, it was developed with the assistance of insurance and legal experts. “We gained valuable insights throughout the process from companies who are already operating ships remotely around the world,” explains Grant Hunter, BIMCO’s director of standards, innovation and research.

“The framework is lagging behind the technology”

According to Capt Hazari, flexibility has been built into the procedures because of the conflicting legal requirements that apply to these ships. For instance, some jurisdictions require remotely-controlled (or autonomous) vessels to be partially or fully manned when passing through their territorial waters or calling at their ports.

Meantime, the paperwork still has a lot of catching up to do. As Bureau Veritas notes: “When it comes to regulations specific to autonomous shipping, the framework is lagging behind the technology. This is largely an issue of complexity. First, there is the fact that the systems and equipment involved are new and are evolving quickly, which makes standardisation a moving goalpost. Second, there is the widespread impact that ship autonomy will have on its operation, which implies that existing instruments and standards will need to be reviewed and updated.

“Third, there is the complicating factor of remote operations. This is a particular sticking point – a vessel and its remote operations centre may not be under the same national regulations, and a single centre may be operating several vessels in different national waters.”

Bureau Veritas, which has developed its own guidelines, agrees with BIMCO that, as the class society puts it, “the regulatory landscape supporting its safe development is still in flux,” noting that large merchant ships “have yet to move beyond a basic level of autonomy because of high costs and concerns about cyber and operational risks.”

Also, the society adds, it is important to make a distinction between automated and autonomous. While the first means the vessel can accomplish a specific and well-defined function, the second requires it to virtually think. That is, self-sufficiently learn, adjust and evolve in response to dynamic environments.

Perhaps IMO’s imminent Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship (MASS) code will answer all the issues. Due for completion by 2025 and mandatory by 2028, it is intended to be flexible enough to encompass technologies that have not yet appeared.

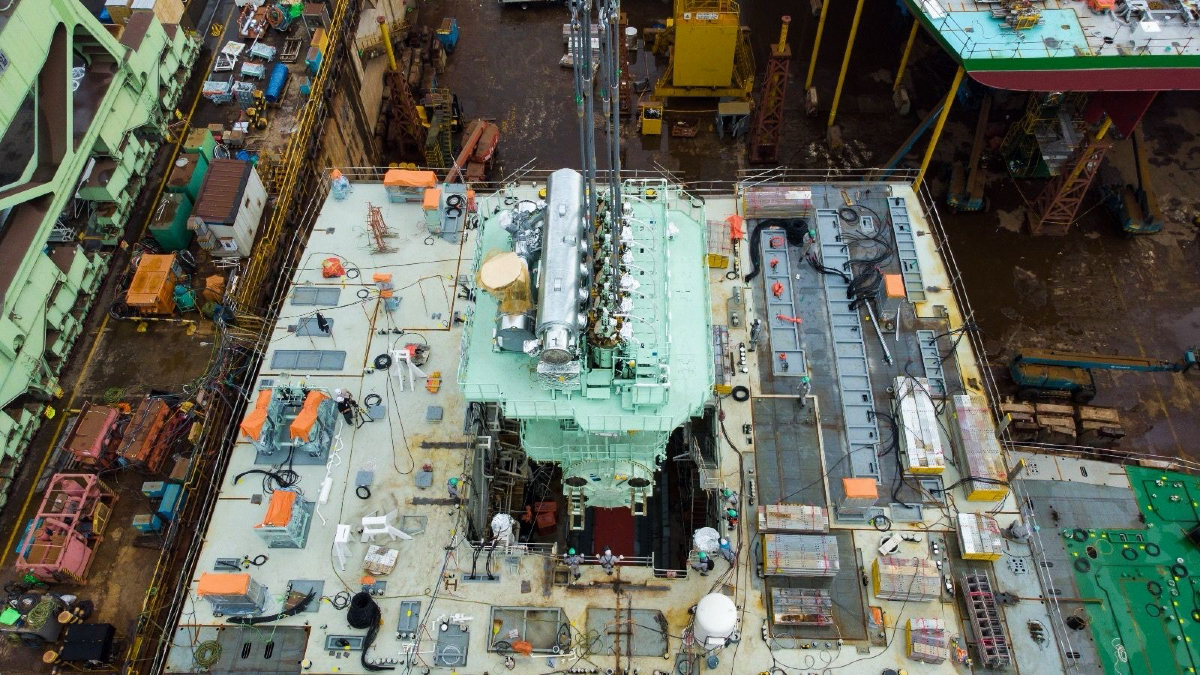

Meantime, one of current leaders in lean-crewed vessels, Ocean Infinity, expects to take delivery from 2025 of the first of six 85-m optionally crewed robotic vessels. Built by Vard in Vietnam, they will be deployed offshore along with Ocean Infinity’s current fleet of nine 21-m and 36-m vessels, and eight 78-m ships.

For its pioneering efforts, Ocean Infinity was named the winner of OSJ’s Offshore Renewables Award in 2024.

Taking a global view, Ocean Infinity announced in early 2024 that it would open a robotic ship operations centre in Tasmania. The Austin, Texas company already has centres in the UK and Sweden and intends to open another in Singapore. At least for a start, the Hobart-based operation will run lean-crewed 36-m hydrographic vessels, as it is doing elsewhere.

“[The 78-m vessels] will allow for onshore remote-controlled, lean-crewed and eventually uncrewed operations,” the company said. Ocean Infinity also refers to “optionally crewed robotic vessels” running on a skeleton crew that “will in due course be capable of working with no personnel offshore”.

In a big first step for the company, in April 2024 Shell signed a five-year deal with Ocean Infinity for skeleton-crewed hydrographic vessels, for which all data processing and payload controls are handled onshore.

“Large merchant ships have yet to move beyond a basic level of autonomy”

In other developments, in September 2024, aluminium specialist Austal and another Australian group, Greenroom Robotics, announced a collaboration on what Austal’s chief technology officer, Dr Glenn Callow, describes as “practical remote and autonomous solutions that may be applied to any watercraft designed or built by Austal.” This follows a successful partnership for the Royal Australian Navy in a pilot autonomy test using a decommissioned 57-m patrol boat.

These and other projects follow in the wake of Yara Birkeland, the autonomous – and zero-emissions – bulk carrier that has been transporting fertiliser between the port of Brevik in Norway and a Yara group plant in Porsgrunn for the last four years. The vessel has a maximum speed of 15 knots and a cargo capacity of 120 TEUs.

Yet, while the proponents of autonomous vessels highlight their efficiency, lower fuel consumption, leaner crews and higher profits, Bureau Veritas thinks otherwise. “We would argue strongly that the number one benefit of increasing ship autonomy is safety,” says the class society, citing the European Maritime Safety Agency that attributes more than 80% of shipboard accidents to human error.

Looking ahead, Bureau Veritas predicts: “It is likely that small- to medium-sized vessels operating in national waters will be supervised by a person on shore.” Crews won’t so much be replaced, as unions fear, but be given new and perhaps more congenial roles.

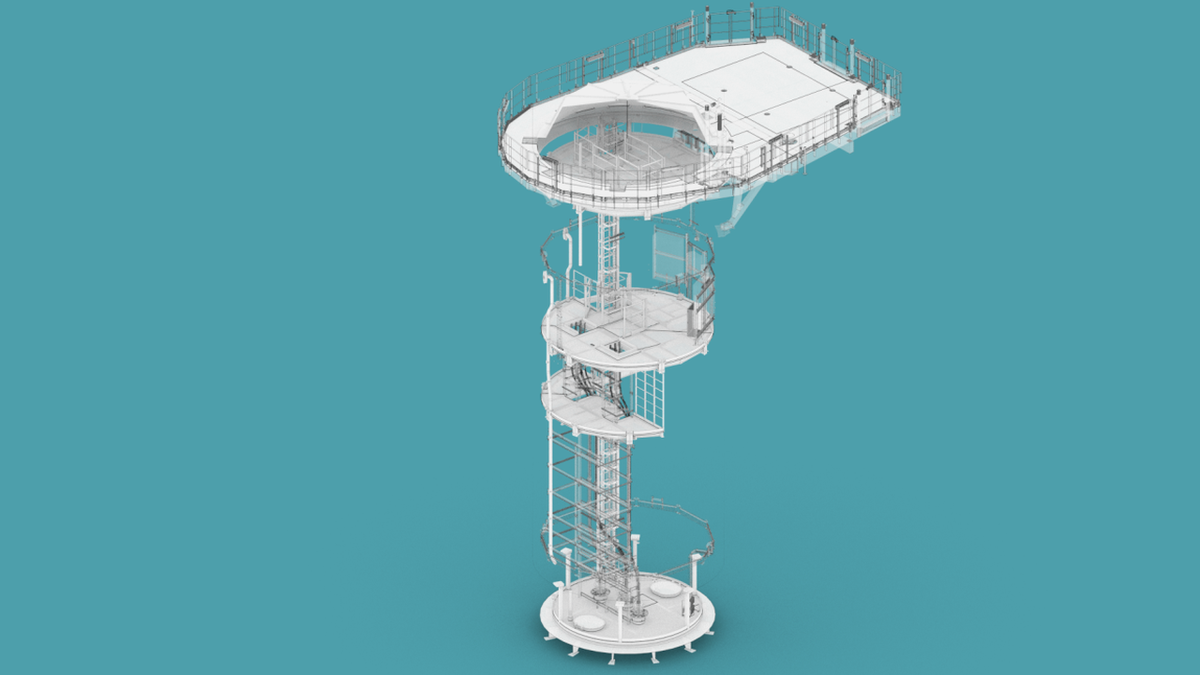

This appears to be where Fjord1 is headed. Fjord1 has contracted Norwegian Electric Systems (NES), a HAV Group subsidiary, to develop systems for the automation of vessel functions and autonomous navigation for the four zero-emissions ferries.

In close collaboration with Fjord1, NES will develop and deliver the systems for the automation of vessel functions and autonomous navigation, including autocrossing and autodocking, which will replace some manual operations on board.

Taking things steadily, it is aiming for full automation and navigation from 2027, with autonomous-only sailing slated for 2028. At that point, a land-based control centre will take over.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.