Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Register to read more articles.

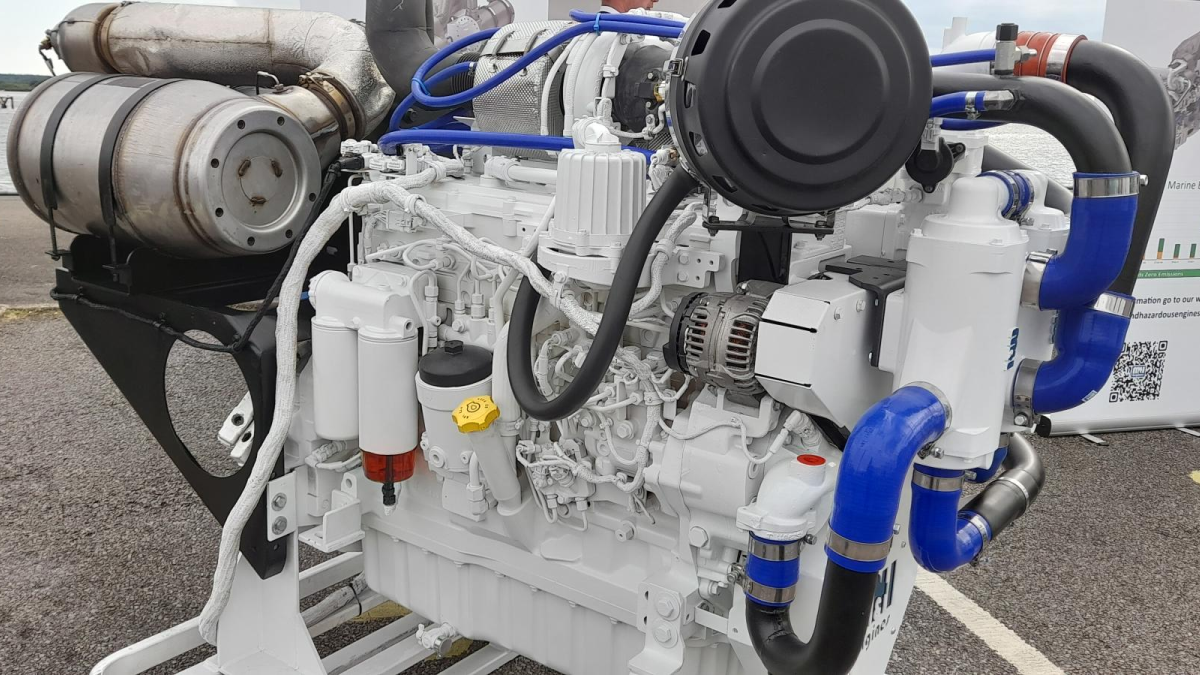

Biodiesel and aftertreatment make engines clean and green

Marine engines can be clean and green if combined with aftertreatment units and sustainable biofuels, enabling vessel owners to achieve net-zero emissions

The latest engines, developed with diesel particulate filters and selective catalytic reduction (SCR) technologies, almost eliminate particulate matter, NOx, SOx and carbon monoxide emissions.

When combusting biofuels derived from carbon capture projects which are independently verified as sustainable, CO2 emissions are minimised, according to M&H Engines founder and managing director Barry McCooey.

He said its marine diesel engines far exceed emissions requirements under the European Union’s Stage V and the US Environmental Protection Agency Tier 4 standards, and requirements from the California air regulatory authority, CARB.

“With an optimised engine, SCR and diesel particulate filter, we have reduced CO, NOx and particulate matter by 99.8% versus EU Stage I to get to as clean and near net zero as possible,” he explained during the Seawork exhibition.

“We made the engine as clean as possible and now we are looking at the fuel. Our C16 fuel comes from carbon capture for carbon-neutral e-diesel.” To produce the fuel, CO2 is extracted from the atmosphere and hydrogen comes from seawater electrolysis to form methane which is combined to form a chain with 16 carbon atoms, Mr McCooey explained to Riviera.

Engines using this biodiesel still require aftertreatment to remove particulates and NOx, but provide an option for vessel operators to go green with existing assets or new engines.

Other options are using methanol and hydrogen-based fuels and from electrification technologies, depending on the vessel design.

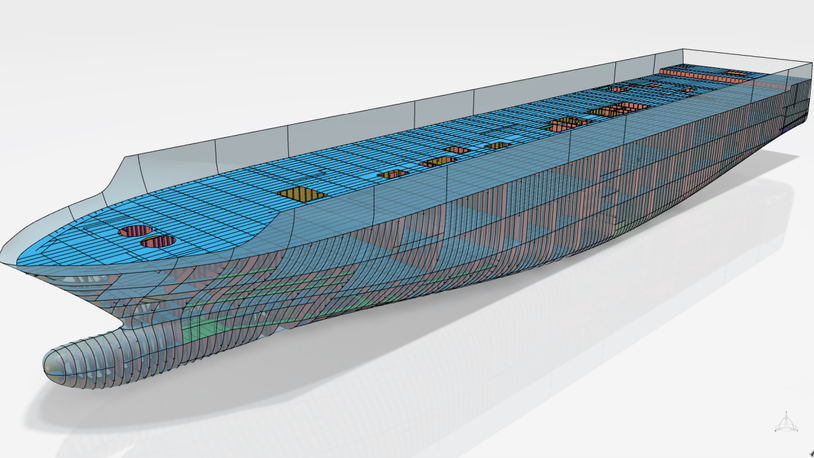

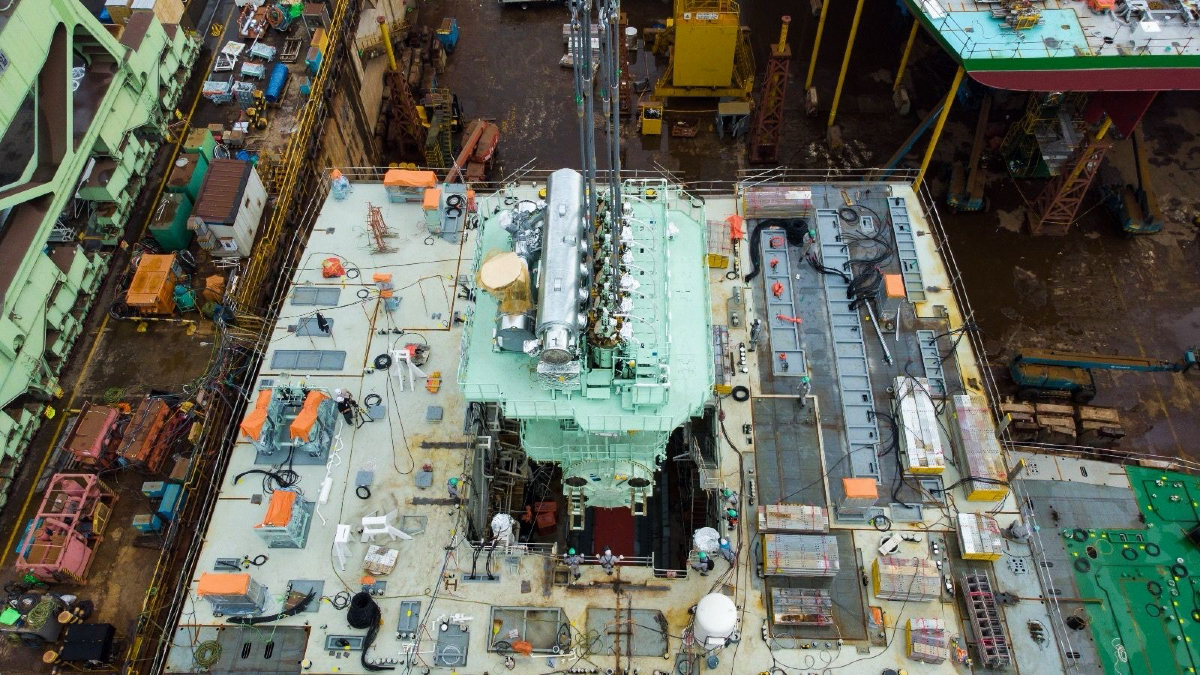

BMT lead for clean shipping Thomas Beard said vessels should be designed based on their operating profile and the storage and handling requirements of fuels.

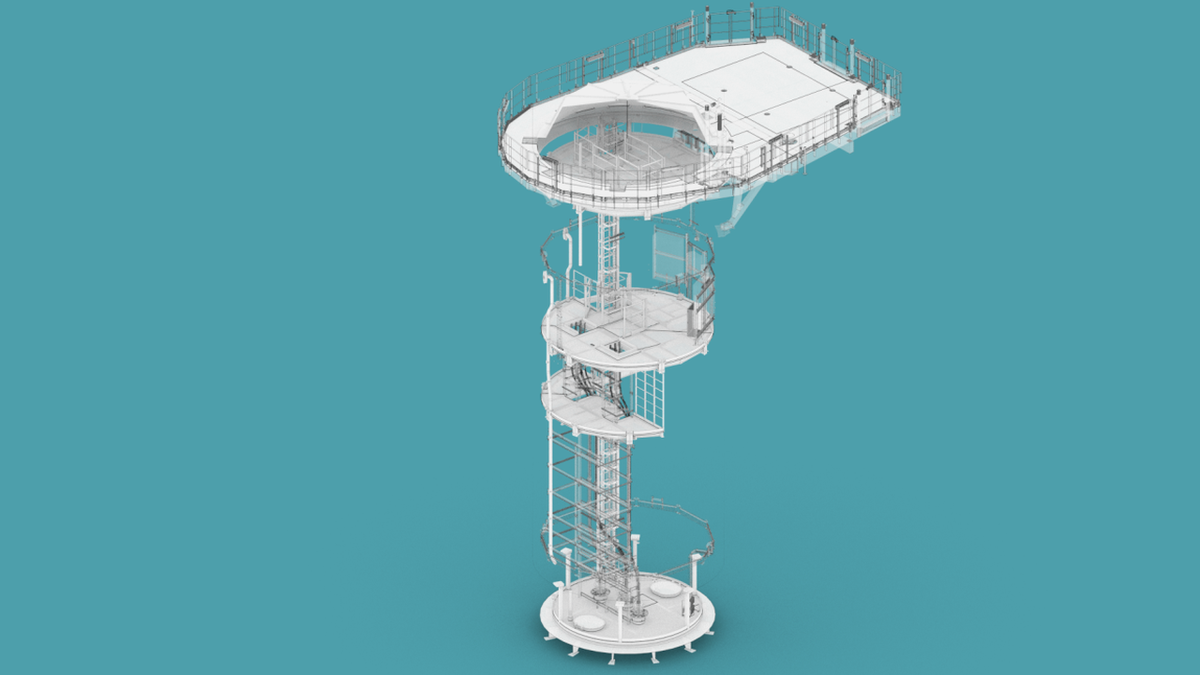

“It is challenging designing where to store fuel, but this drives the design,” he said. Other considerations are the characteristics of the fuel, its toxicity, flammability and requirements for its handling, venting and leak dispersal. Double-walled piping, large processing areas, gas-proof airlocks, safety stations and hazardous zones may be required.

When designing vessels, naval architects also need to understand leak dispersal in different weather conditions. “It is a big part of where the gases go – you do not want it over the bridge,” said Mr Beard. “We need to ensure seafarer and passenger safety.”

For alternative fuels on tugboats, dispersal of any leaking gases needs to be monitored as “as the cloud could go over the assisted ship.”

On vessels carrying passengers, such as ferries and crew transfer vessels, fuel storage enclosures need to be completely gas tight to prevent leaks.

Flag, coastal state authorities and classification societies also need to be involved early in design projects to ensure designs and vessels are approved.

The UK Maritime & Coastal Agency (MCA) has produced guidance (MGM 664) for vessels using alternative fuels and battery-electric propulsion. “This is a certification pathway” for vessel owners and designers planning to build vessels, said MCA assistant director for regulatory innovation Keith Johnstone. “There is likely to be a patchwork of fuels and electric solutions.”

MCA modelled the type of fuels suitable for different ship types and discovered electrification was the best option for workboats, while a range extender would support operations further from shore. “Longer-range vessels could use methanol and compressed hydrogen, while for larger ships it could be ammonia or small nuclear reactors,” said Mr Johnstone.

MCA has updated the Workboat Code edition 3 with annexes for those operating on alternative propulsion and for remotely operated vessels. MCA lead for vessel codes Rob Taylor said Annex 1 of the code primarily considers vessels with battery and hybrid propulsion, and hinted there would be more work done to include other alternative fuels in the Workboat Code in the future.

UK Chamber of Shipping environment policy director Francesco Sandrelli provided real-life examples of vessel owners reducing emissions by adopting technology. He mentioned CMB’s Hydrocat and Hydrotug, which use compressed hydrogen in dual-fuel engines and SMS Towage using shore power in Portsmouth and Belfast ports in the UK to cover energy requirements on its fleet of tugs.

He said one of the next steps was introducing vessel charging in offshore windfarms, to support electric-powered service operation vessels and crew transfer boats.

Maritime Decarbonisation, Europe: Conference, Awards & Exhibition 2024address critical environmental issues head-on. Focused on the industry’s energy transition, the conference offers a comprehensive forum for stakeholders across the maritime sector to explore solutions and strategies for achieving low-carbon shipping and zero-emission shipping

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.