Business Sectors

Events

Contents

Register to read more articles.

CO2 shipping and storage: Europe and Asia take different routes to market

Europe builds hardware; Asia builds frameworks - both regions are shaping the future of CO2 shipping in markedly different ways

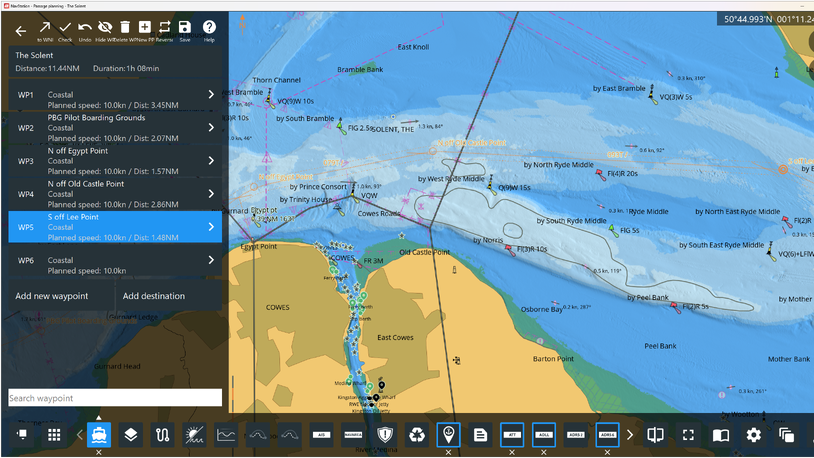

Tanker shipping and trade has entered a transitional phase, not only in terms of fuels but in the very nature of what ships are asked to carry. As carbon capture and storage (CCS) gathers political and commercial urgency, a new maritime sector is taking shape: the transport of carbon dioxide (CO2) by sea. Two regions are emerging at the forefront — Europe and Asia — but their approaches are anything but aligned.

Europe is pressing ahead with vessel construction and pilot projects centred on high-profile initiatives such as Northern Lights and the development of LCO2 tankers. Asia, meanwhile, is moving with policy co-ordination, port-to-port testing, and national-level partnerships. The ships are coming, but it remains to be seen where a coherent market will first emerge.

In March 2025, Hyundai Mipo Dockyard began construction on the first of four LCO2 tankers for Capital Gas Ship Management, part of the Evangelos Marinakis-led Capital Group. Each vessel will have a capacity of 22,000-m³ and is being constructed with dual-fuel capabilities and specialised containment technology. As CO2 carriers, the Marshall Island-flag vessels will also be fitted with a pioneering carbon capture and storage (CCS) system under an agreement between Capital Gas, ERMA FIRST and Babcock.

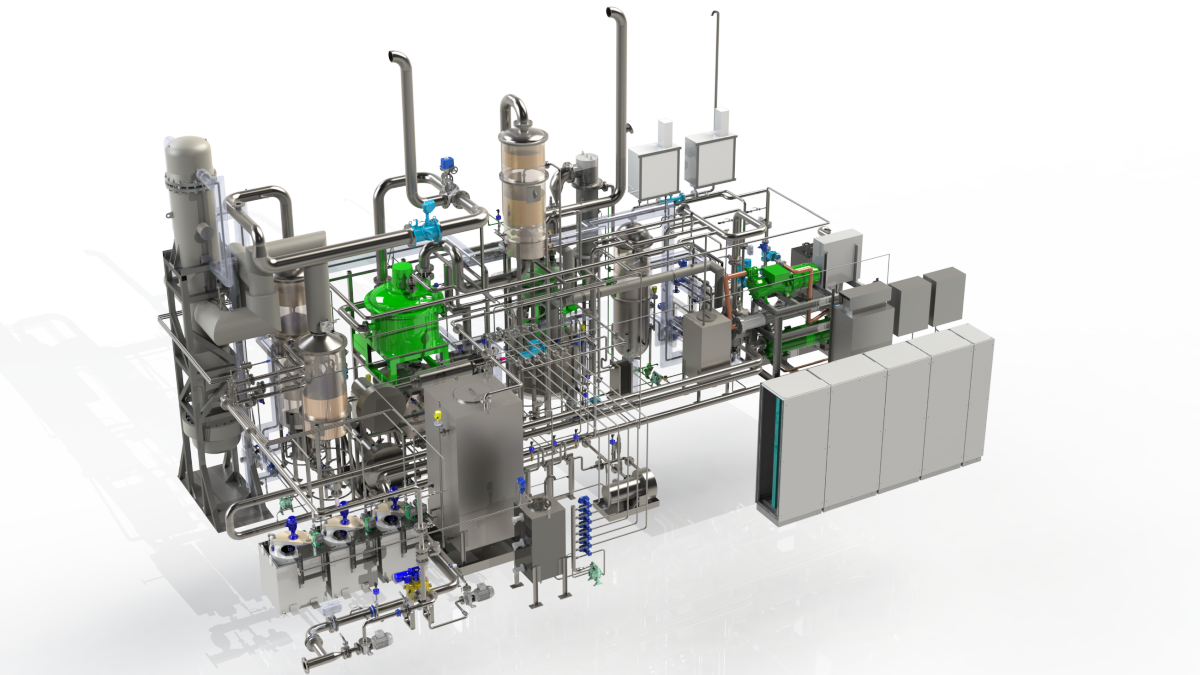

The ERMA FIRST Carbon Fit system received approvals in principle from both Lloyd’s Register and DNV. It uses amine absorption technology based on a proprietary amine solvent to absorb CO2 from flue gases. The resultant mix is then heated to produce a chemical reaction that reverses the absorption, separating the CO2 from the solvent. Subsequently, the released CO2 is liquefied using Babcock LGE’s ecoCO2 system and stored on board the ship in pressurised low-temperature storage for subsequent offloading. Since the regenerated solvent can be reused, the process creates a highly efficient regenerative loop for CCS, according to the developers.

“These vessels are not just about transporting LCO2, [but also] they represent a step toward the future of carbon management, embracing new technologies that align with the evolving needs of the industry,” said Capital Gas Ship Management in a social media post. While the project is described as “pioneering” by the yard, the development is still taking place in a vacuum of functioning cross-border CO2 transport arrangements.

At the same time, companies such as ECOLOG are putting forward scalable carrier concepts aimed at enabling point-to-point carbon transport. ECOLOG’s low-pressure 40,000-m³ LCO2 tanker has received Approval in Principle (AiP) from ABS. The design targets medium-haul routes between emitters and sequestration points, and the company argues it offers “a technically and economically viable option.” Yet even ECOLOG’s senior executives acknowledge that regulatory frameworks are not developing in tandem with the technology.

ECOLOG is also currently developing three significant CO2 export terminals, and is spending "90% of our time" on terminal development and emissions volume aggregation, according to ECOLOG chief commercial officer, Jasper Heikens. The company’s portfolio includes a floating liquefaction unit in Greece and land-based terminals in Korea and the Netherlands, positioning itself as an infrastructure orchestrator between emitters and storage sites.

"We are kind of in the middle between the sequestration site and the emitter," Mr Heikens explains. "We sometimes have to be an orchestrator, like the glue getting everyone together and facilitating the development of the full supply chain."

However, he notes major industrial emitters are pushing back on decarbonisation costs. These companies have indicated government support is crucial for maintaining European operations.

“Senior executives acknowledge that regulatory frameworks are not developing in tandem with the technology”

The situation is particularly acute given current market conditions. High energy prices and decarbonisation requirements are driving concerns about European de-industrialisation, with multinational companies evaluating their continued presence in the region. Mr Heikens cites examples of international chemical companies considering facility mothballing in Europe while maintaining production elsewhere.

This tension was echoed in a report warning that the United Kingdom faces an “18-month window” to ensure CO2 shipping infrastructure keeps pace with carbon storage plans. If it fails to align port readiness with pipeline development and shipping capabilities, much of the planned CO2 sequestration capacity could be left inaccessible.

Northern Lights illuminates progress

Perhaps no European project is more closely watched than Northern Lights, the carbon transport and storage joint venture between Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies. The initiative aims to transport liquefied CO2 by ship to a receiving terminal in Øygarden, Norway, from where it will be injected into undersea geological formations. Northern Lights is often cited as evidence that Europe is leading the development of maritime CO2 transport infrastructure.

In April 2025, Northern Lights announced it had delivered its plan for development and operation of the expansion phase to the Norwegian Ministry of Energy, seeking approval of the development plan. The expansion project will increase transport and storage capacity to a minimum of five million tonnes CO2 per year, following the signing of a commercial agreement to transport and store up to 900,000 tonnes of CO2 from Stockholm Exergi annually. The expansion is enabled by a grant from the Connecting Europe Facility for Energy (CEF Energy) funding scheme.

Stockholm Exergi is Northern Lights’ third commercial customer, along with Yara in the Netherlands and Ørsted in Denmark. In addition, Northern Lights will transport and store CO2 from Norwegian emitters Hafslund Celsio in Oslo and Heidelberg Materials in Brevik, as part of the government-supported Longship project.

Yet, despite the progress, questions remain over scalability and access. Even with the newcomers, only a handful of emitters are connecting to the Northern Lights value chain. While the first two dedicated LCO2 carriers are in the water, the broader regulatory environment across the European Union is fragmented. Carbon waste shipping remains a non-harmonised activity in many jurisdictions, with legal classification of liquefied CO2 varying across borders.

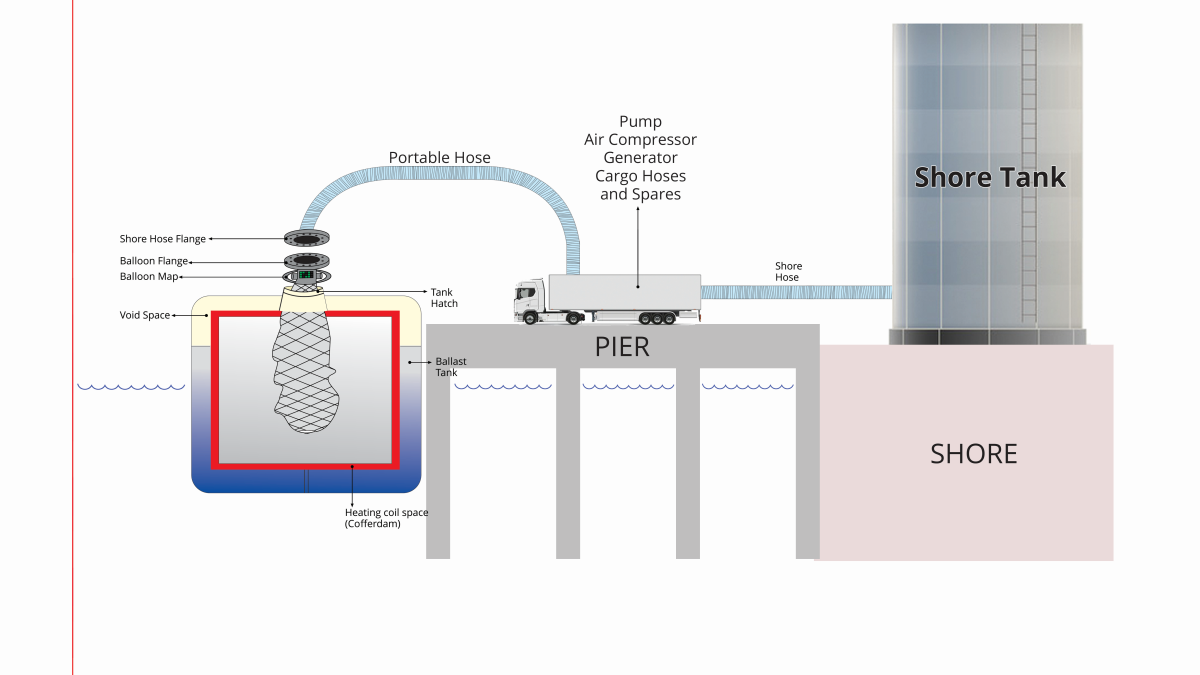

Beyond point-to-point LCO2 carriage, another approach has been gaining traction — onboard carbon capture and storage (OCCS). In January 2025, Seatrium completed Japan’s first retrofit of an OCCS aboard an LR1 tanker. The refit involved a solvent-based system, designed to capture CO2 from the ship’s exhaust gases and store it onboard for discharge at port.

The project is part of a broader feasibility study by Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha (K Line), which is exploring OCCS across multiple vessel types. Although the system has been successfully installed, a Riviera webinar on the subject noted that “onboard carbon capture faces hard questions,” particularly with regard to space requirements, energy consumption, and the availability of discharge infrastructure.

The OCCS systems also introduce new crew training requirements and require the installation of additional monitoring and validation equipment. These limitations mean that the technology may not be applicable across all vessel classes or trade routes.

Smaller projects, greater co-ordination

If Europe has taken a technology-first approach, Asia appears to be favouring co-ordination and coherence. A Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation/Boston Consulting Group report on the Asia-Pacific region, titled Opportunities for Shipping to Enable Cross-Border CCUS Initiatives, December 2024, outlined the steps being taken in countries including Japan, South Korea, and Singapore to build functional CO2 shipping corridors.

In Japan, the government has introduced a regulatory roadmap to enable CO2 transport by sea, tied to national emissions reduction commitments. South Korea is moving forward with government-backed pilot projects involving KNCC and major energy firms. Singapore is positioning itself as a future hub for liquefied CO2, with regulatory work underway to facilitate ship-to-ship transfers and storage operations.

“Government support is crucial for maintaining European operations”

The report concluded that “Asia’s progress is defined less by individual ship orders and more by whole-of-government policy support.” In contrast to Europe’s shipyard-led development, Asia’s emerging CO2 transport sector is rooted in policy instruments, industrial partnerships, and regional memoranda of understanding.

One such example is the collaboration between Japan, South Korea, and Malaysia to explore inter-regional CO2 shipping routes. The pilot projects include feasibility studies, port readiness assessments, and legal reviews designed to smooth future trading relationships.

Networked solutions

In a parallel development, Japan’s ENEOS, NYK Line, and Korea’s KNCC are jointly exploring the use of floating CO2 storage units. These floating units would serve as offshore reservoirs for captured CO2, enabling more flexible offloading schedules and mitigating congestion at land-based storage terminals.

While these floating units remain at the conceptual stage, they reflect a growing view in Asia that CO2 transport and storage cannot be solved through fixed infrastructure alone. Flexibility, interoperability, and regional co-ordination are seen as prerequisites for commercial viability.

The development mirrors concerns raised in Europe, where fixed-point storage models are being questioned for their scalability. If ports or pipelines experience delays, LCO2 carriers may find themselves without a discharge option — a risk that floating storage could mitigate.

The divergence in approach raises a critical question: who is more likely to create a working CO2 shipping market first? Europe has made early technological progress, backed by capital investment and high-profile project branding. However, regulatory alignment, infrastructure investment, and cross-border agreements remain sporadic.

Asia’s path is arguably slower in terms of tonnage delivered but appears more grounded in future usability. If ships are ready before discharge ports and legal frameworks, they may remain idle. Asia’s emphasis on early-stage regulatory development and pilot projects seeks to prevent this scenario.

At the heart of this divide lies a tension between capacity and capability. Europe is demonstrating that it can finance and operate the ships; Asia is demonstrating that it can build systems.

Some stakeholders have drawn parallels with the early development of the LNG shipping market. During LNG’s early years, Asian buyers and governments invested in import terminals and long-term offtake contracts, creating demand pull that eventually triggered global supply expansion.

By contrast, Europe’s LNG market took longer to develop, constrained by regulatory fragmentation and infrastructure bottlenecks. If history repeats, Asia may again outpace Europe in converting technical readiness into functional trade.

There are no guarantees that either approach will succeed. Onboard carbon capture remains technically complex and may struggle to find a route to commercialisation without regulatory credits or emissions pricing support. LCO2 carriage relies on infrastructure that does not yet exist at scale. Even floating storage solutions require classification, regulatory approval, and operational validation.

Nevertheless, the development of CO2 shipping infrastructure is no longer a theoretical discussion. Ships are being built. Retrofits are being installed. Joint ventures are being formed. What remains to be seen is whether policy, law, and investment can keep pace with ambition.

The role of shipowners, financiers, and infrastructure developers in building viable CO₂ transport models is a central focus of the CO₂ Shipping and Terminals Conference. With contributions from Capital Gas, Northern Lights, ECOLOG, and Societe Generale, this event explores how stakeholders are bridging the gap between ambition and execution.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Environmental Protection Webinar Week

Cyber & Vessel Security Webinar Week

The illusion of safety: what we're getting wrong about crews, tech, and fatigue

Responsible Ship Recycling Forum 2025

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.