Business Sectors

Contents

Vessel owners challenged by rapid pace of DP developments

Offshore oil and gas is a client-driven industry. Although there are many other bodies that provide advice and guidance to vessel owners there is little doubt that clients have the greatest influence in forming the behaviours of those that provide services to them. The history of the past 40 years provides ample evidence of that, and it applies as much to the DP sector of the offshore industry as to other service sectors.

Many oil companies were nervous and distrustful when DP was first introduced, and maybe some still are. Famously, one of the oil majors just did not accept DP offshore support vessels (OSVs) until relatively recently. However, those days belong in the past and even that oil major has had a change of mind. However, the fact is that DP OSVs are here to stay.

Although accurate figures are difficult to get hold of, one recent study showed that 35 per cent of the world’s approximately 8,000-strong OSV and anchor-handling tug/supply (AHTS) fleet is fitted with DP. Given that almost all newbuild OSVs are DP – most being DP class 2, some DP class 3 – that percentage is sure to rise. Not only are there many more DP OSVs, the vessels themselves are also increasing in size, power and weight, a direct consequence of which is an increase in potential impact damage should position be lost when close to an offshore structure.

Many of today’s OSVs are huge vessels in comparison to those of the 1980s when few, if any, were DP. Today, the majority are DP. In the 1980s an AHTS of 65m length was a sizeable vessel whereas today 90m is quite normal. Even greater increases have been experienced in power and bollard pull, with the latter rising from a good average of 100 tonnes in the 1980s to levels more than twice that – in excess of 250 tonnes – today. The growth in size and power is partly related to the oil and gas industry’s expansion into deeper waters and in harsh environment areas where smaller, less powerful vessels struggle to provide the required support.

To an oil company these vessels present a contrasting image. They are an essential link in the supply chain at the same time as presenting a high-consequence hazard. By the very nature of their work OSVs and, increasingly, DP OSVs spend more time in close proximity to offshore assets than other vessel types. Hence, in many respects, DP OSVs present the highest risk to the asset owner.

Against this background of large powerful vessels sitting for long periods of time in very close proximity to vulnerable offshore assets, it is hardly surprising that the client will expect these vessels to deliver reliable and robust position-keeping performance.

The introduction of DP into the OSV market followed a quite different route from other vessel types serving the offshore oil and gas industry. Even a superficial look at the genealogy of DP will show that DP was introduced to support offshore activities that otherwise would have remained out of reach. For example, the first DP system of 50 years ago was designed specifically to support seabed coring in deep ocean waters and, from then on, gradually to deepwater DP drilling activities, although it is only in the last 10 years or so that we have seen an almost exponential rise in the number of deepwater DP drilling units.

Soon after its launch 50 years ago, DP was being used increasingly as the main means of positioning for dive support vessels (DSVs), ROV and survey vessels, construction vessels and pipelayers. Much of the work that these vessels do would not be possible were it not for DP.

However, that is not the case for OSVs. The basic role of the OSV has not materially changed in the last 30 years. OSVs are still required to maintain position for long periods at rigs and platforms discharging, back-loading, pumping fluids and transferring bulk. Without DP there are a number of options for positioning OSVs. Mooring practices using a combination of anchors and/or ropes are still performed in some locations. Where not practicable, manual and/or joystick control can be used.

There is good reason to suggest that OSVs could still be providing support and carrying out the full range of activities in offshore oil and gas even without DP. However, with DP the job is easier. It makes it possible for the OSV to stay on location automatically for extended periods, whilst at the same time relieving masters and bridge officers from the stress and workload brought about by hours of effort on manual or joystick control.

In the early days of DP OSVs, both owners and clients were largely influenced by the perception that DP was an alternative to other methods of station keeping. It was quite normal for manual/joystick and DP control to be interchangeable at the work site. If DP failed for whatever reason, usually position reference systems, then the work would continue on manual or joystick control. This led to a mindset that DP OSVs are somehow ‘different’ from other DP vessels.

Evidence of that mindset was that, typically, the level of control, inspection, audit and manning of DP OSVs was less than for other DP vessel types. For example, whereas a DP DSV would be audited, inspected and subjected to seemingly interminable trials and tests, a DP OSV for the same client would get off lightly, usually receiving scant attention as it was taken on hire from the spot market.

In some parts of the industry, that more forgiving approach still prevails. However, the basis for that view is flawed. Increasingly, oil-company clients and other clients expect DP OSVs to attain a level of technical and operational safety and performance to match the attendant risks these vessels present. In short, this means that more and more clients impose the same level of expectation on DP OSVs as they do on DP DSVs, DP construction vessels, pipelayers, crane vessels and drilling units.

This article addresses these client expectations, but first of all it is important to note that it is not a consistent picture. For some clients, expectation levels remain relatively low. For others, it is the opposite. For many, the expectation may vary under the influence of other business imperatives. Given that the maritime sector of offshore oil and gas is predominantly self-regulating, the recent US Coast Guard initiative apart, that will always be the case. However, in this author’s view, client expectations are on a consistently upward trend. What does this mean for the owners of DP OSVs? What should DP OSV owners be aware of?

First of all, the DP OSV owner should have a thorough understanding of the standards and guidance that are available for the design, construction, management and operation of DP vessels. Is it enough to rely on classification society DP rules? The honest answer is to say no. However, many owners go no further than subscribing to the compliance culture which goes little beyond obtaining class approval.

The basis for almost all standards and guidelines relating to the technical and assurance aspects of DP vessels is found in IMO MSC Circ 645 – ‘Guidelines for Vessels with Dynamic Positioning Systems’. Published in 1994 these guidelines have been used by all classification societies in the development of their DP rules. Although each class society has interpreted IMO 645 slightly differently they have not undermined the early principles. Whereas class DP rules continue to evolve over time with many class societies issuing annual revisions of their DP rules, IMO 645 remains fixed in time and is unchanged. It says much for those who drafted IMO 645 that they provided such a solid basis for the DP rules that were subsequently developed.

IMO 645 also provides the philosophical basis for most of the standards and guidelines issued by industry bodies. The most active of these over the last 20 years or so has been London-based International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA), formerly the DPVOA (Dynamic Positioning Vessel Operators Association). With an international membership of over 800 organisations in more than 60 countries, IMCA can justifiably be considered the most influential representative of the DP sector. Its IMCA M Series of publications provides more than 50 sets of guidelines on DP-related topics. Significantly, a number of IMCA’s M Series can be found as stated requirements in the small print of many oil company contracts, in particular the various IMCA guidelines relating to DP failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) and annual DP trials. These M Series guidelines expand considerably beyond what class has to say about DP.

Two years after the publication of IMO 645, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) published another set of DP guidelines, IMO MSC Circ 738 ‘The Training and Experience of Key DP Personnel.’ IMO 738 provides the benchmark for the critical area of operator training, experience, qualifications and certification, and is the basis for many operator competency programmes. The influential role of IMCA in the DP sector is underlined by the fact that IMO adopted, without amendment, the IMCA-published guideline IMCA M 117 ‘Training and Experience of Key DP Personnel’ and published it as IMO 738.

The role of provider of industry guidelines is no longer the unique preserve of IMCA – in recent years the US-based DP Committee of the Marine Technology Society (MTS) has been active on that front. In 2010 and 2011, MTS published two guidance documents, one on DP operations and the other on DP vessel design philosophy. Unlike the trade association roots of IMCA, the DP Committee of MTS is a totally independent body, comprising individual members from across the global DP community, whose stated mission is to promote a greater international understanding of dynamic positioning and related issues.

The MTS guidance document on DP operations has been adopted by DNV and was issued in January 2011 as a DNV recommended practice, DNV-RP-E307. It is perhaps too early to predict the influence that these MTS guidance documents will have across the DP sector although it is known that at least one oil major is in the process of adopting them.

What emerges from the brief overview is that owners should not only be aware of what clients are thinking but also where they are turning to for their inspiration. Informed and diligent clients look for assurance that the vessels they take on hire, DP OSVs included, are technically acceptable and that they are operated safely with competent crews.

In practical terms this means the owner is likely to be asked to submit to the client a series of documents and provide other evidence that the required standards have been achieved. These documents will include the vessel’s DP FMEA, the annual DP trials reports, vessel DP operating manual and procedures, as well as details of how competency and manning standards are set and achieved.

The DP FMEA is the single most important document relating to the technical capability of a DP vessel and has its roots in IMO 645, where section 5.1.1.1 specifies: “Initial survey which should include a complete survey of the DP system to ensure full compliance with appropriate parts of the guidelines. Further it includes a complete test of all systems and components and the ability to keep position after single failures associated with the assigned equipment class...”

Without exception in the DP sector, including the classification societies, this specification has been interpreted that a DP vessel requires a DP FMEA and a set of DP FMEA proving trials. There may be other ways of performing a “complete survey of the DP system” and a “complete test of the DP system” but in the DP sector it is the FMEA and proving trials.

Similarly, without exception, classification societies require owners or shipyards to produce DP FMEAs and to conduct DP FMEA proving trials to the satisfaction of the society prior to the award of a DP class notation; for example, for a DP Equipment Class 2 vessel DNV issue an equivalent AUTR or DPS2, Lloyd’s issue DP (AA), ABS issue DPS-2. Class will require compliance with the relevant DP class rules for the chosen DP class notation. Once the DP FMEA and the DP proving trials are approved the documents will be stamped and the DP class notation will be awarded.

On the face of it this process of class compliance should be sufficient to ensure that class-approved DP FMEAs and proving trials are at a consistent standard across the industry and that they meet the requirement for a complete survey of the DP system and a complete test of the DP system as interpreted by each class society in its own DP Rules.

The reality is rather different. The class route has achieved neither consistency nor has it achieved a high standard. The reasons for this are many and varied, the outcome being that the class society compliance and approval process does not deliver DP FMEAs and proving trials of sufficiently high quality on a consistent basis. Without identifying the class societies or the DP vessel owners or shipyards involved, this author has seen many very poor quality DP FMEAs and proving trials documents, all of which have been approved by class and been the basis for awarding a DP class notation and, presumably, have made the owner confident that their vessel is suitably surveyed and ready to operate.

One example of a class-approved DP FMEA that GL Noble Denton recently reviewed for an oil company turned out to be a superficial analysis and exposed an alarming number of mistakes, including:

• the vessel’s worst case failure not identified

• inaccurate and misleading load calculations that could lead to blackout in certain conditions

• inaccurate understanding of the as-built fuel system and consequent failures in the analysis

• no analysis of the air-operated cooling water valves

• misrepresentation of the battery backup system and distributions

• inaccurate understanding of the thruster cooling system and failures in the analysis

• omission in the proving trials of auxiliary systems and position reference systems.

Even given all of the above-mentioned, this was not the worst DP FMEA that we have come across.

What this demonstrates above all else is a failure in the ability of the class approval process to guarantee the adequacy of DP FMEAs. Clearly, failures like these do not happen on every occasion but they happen often enough to worry those that have a vested interest in needing DP FMEAs to be fit for purpose.

Fortunately, most clients now look beyond the fact that a DP FMEA might have class approval. They look more critically at DP FMEAs and also look to other sources for appropriate standards and guidance, for the most part IMCA.

IMCA has published a number of important FMEA guidance documents, including:

• IMCA M 166 – ‘Guidance on Failure Modes and Effects Analysis’

• IMCA M 178 – ‘FMEA Management Guide’

• IMCA M 206 – ‘A Guide to DP Electrical Power and Control Systems’

• IMCA M 04/04 – ‘Methods of Establishing the Safety and Reliability of DP Systems’.

In addition, the MTS guideline document ‘DP Vessel Design Philosophy Guidelines’ has now joined that list. Each of those documents provides authoritative guidance to the industry on conducting the analysis, in managing the DP FMEA process and in conducting proving trials.

References to these IMCA guidelines are frequently made in the introductory sections of DP FMEAs accompanied by stock phrases claiming that the analysis has been conducted in accordance with them.

Clearly, however, this is not always the case. The informed and diligent oil company client or their third-party reviewer will discover this with the likely result that it will cause difficulties for the DP vessel owner, either in rejection of the vessel or having to make good the deficiencies in the DP FMEA through further analysis and, in some cases, requiring a complete re-analysis and testing of the DP system. Not only can this be time-consuming and expensive, it is also likely to have an adverse commercial impact and will dent the owner’s reputation with that oil company as well as limiting future contract opportunities.

The prudent DP vessel owner shouldn’t get into that situation. The DP FMEA and the proving trials for each of their vessels should meet sufficiently high standards that will give the owner, and all potential clients, assurance that the DP system redundancy/fault tolerance criteria are met.

Translating this into action, what does the DP vessel owner do? Some may play the percentage game and hope that their clients will be more forgiving and do nothing. That is a dangerous game since who knows what single faults have been ignored, missed, poorly analysed or inadequately tested.

The prudent owner will do otherwise and take positive steps by carrying out a review of their DP FMEAs to determine whether they do meet high enough standards. It is not a painless process, however, and will mean additional cost, time and commitment from owner management plus the difficult task of identifying an organisation or consultant that can perform a competent review and give impartial advice if the owner doesn’t have the expertise in-house.

As with the DP FMEA, the practice of conducting annual DP trials has its basis in IMO 645, paragraph 5.1.1.4: “Annual survey should be carried out within three months before or after each anniversary date of the initial survey. The annual survey should ensure that the DP system has been maintained in accordance with applicable parts of the guidelines and is in good working order. Further an annual test of all important systems and components should be carried out to document the ability of the DP vessel to keep position after single point failures associated with the assigned equipment class.”

Classification societies have taken their cue from the IMO guidelines and interpreted IMO’s expectations in their own way with much the same results as with the DP FMEAs; that is, without consistency of implementation or thoroughness of testing, in some cases even without testing.

DNV rules for annual surveys of DP systems are found in Part 7 (Ships in Operation), Chapter 1 of the DNV Ship Rules under Survey Requirements. Among the main elements of DNV’s approach is that the annual survey is likely to be carried out during regular operations rather than during a dedicated sea trial. This means that certain tests will not be carried out if considered unsafe or even inconvenient to do so. Tests that are likely to be omitted are battery endurance, emergency stops and changeovers.

For DNV the annual survey is primarily as follows:

• functional demonstration that the DP system is operational with some testing of alarms

• visual check to ensure that everything appears in order

• document review to check maintenance, hardware and software changes and FMEA updates.

There is no requirement during the DNV annual survey to fail components. Given that IMO guidelines refer to single point failure tests of all important systems and components this DNV interpretation appears to miss the target.

ABS vies with DNV as a classification society with the largest number of DP vessels on their client list. ABS shares a similar philosophy to DNV in that the annual survey should principally be a short functional demonstration of the DP system with very limited testing of failure modes. The ABS rules for annual surveys of DP systems are found in Part 7 of their Rules for Steel Vessels.

The main points of the ABS rules are:

• special consideration may be given, subject to the discretion of the surveyor, when sufficient test reports are in place demonstrating that the vessel has been engaged in a DP testing programme

• vessel is to be operated for at least two hours at each annual survey to demonstrate that the DP system has been maintained properly and is in good working order

• the operational testing is to be carried out to the surveyor’s satisfaction and does not include the complete performance tests to demonstrate the level of redundancy in the FMEA.

In addition, the ABS surveyor is to generally examine DP equipment (list provided in the ABS rules) so far as can be seen.

Whereas DNV and ABS are the market leaders in DP classification, other main class societies such as Lloyd’s Register and Bureau Veritas follow a similar path of visual inspection, document review and limited functional testing while the DP vessel is operational. It is one of the lesser lights in DP classification, namely Germanischer Lloyd (GL), that introduces a more pro-IMO 645 approach to annual surveys of DP systems with words in their rules that match the IMO wording, as follows: “Further, an annual test of all important systems and components shall be carried out to document the ability of the DP vessel to keep position after single failures associated with the assigned class notation.”

What is the situation with clients? How do they perceive annual DP trials? Is there a typical perception or not? An information-gathering exercise carried out during the preparation of IMCA’s recently published IMCA M190 ‘Guidelines for Developing and Conducting Annual DP Trials Programmes’ revealed that the customary classification society approach consisting of a document review and short functional testing was not enough to meet their expectations.

What clients looked for was annual testing that demonstrated the vessel’s ability to maintain position after single point failures and which tested the protective functions in the DP system as well as its functional performance. This is the approach that prudent owners have adopted for many years and one which has been long advocated by IMCA and now also by MTS in their DP Operations Guidance as well as by DNV who, in spite of having a less rigorous requirement in their DP Class rules, have published the MTS guidance verbatim as a DNV recommended practice, DNV-RP-E307.

The trend towards more thorough annual survey and testing of a vessel’s DP system appears to be unstoppable. IMCA’s M190 provides the industry with the latest, most comprehensive guidance on how to develop and conduct annual DP trials.

Contrary to some misperceptions, it is the vessel owner or vessel operator, not the consultant, who is solely responsible for the development and the conduct of the annual trials. The majority view among clients is that the attendance of a competent and experienced third party at annual DP trials provides a degree of independence and objectivity to the trials and that this is preferable to trials being an in-house exercise.

What does this mean for a DP OSV owner? As in the case of owners with DP FMEAs of questionable quality, an owner who does not have a programme of annual trials and who relies on the class annual survey approach is increasingly likely to face problems from clients whose expectations are higher than the owner’s offerings. This will require many owners to take a step-change in how they do things and will involve developing and conducting an annual DP trials programme in line with the latest IMCA guidance M190.

It is commonplace in the industry for annual DP trials to be viewed as a repeat of the DP FMEA proving trials. In some parts of the world the expression ‘FEMA’ is used to describe the trials programme. Not only is that a distortion of the term ‘FMEA,’ it is also confusing and betrays a lack of understanding of what lies behind each set of trials.

The purpose of the DP FMEA proving trials is, as the name suggests, to prove the findings of the FMEA. FMEA trials focus on proving that worst case failure design intent is not exceeded and that the failure effects are as expected. They are also used to clarify uncertainties that may have arisen during the desktop analysis and which can only be answered by testing and finding out the failure effects. FMEA proving trials are consequently extensive and potentially time-consuming.

Annual DP trials are closely related to the DP FMEA proving trials yet their focus is different. Annual DP trials:

• demonstrate that the DP system is fully functional, performing as intended with full power and thrust availability

• verify the level of redundancy established in the FMEA

• verify the effectiveness of essential protective functions and alarms

• verify that the failure modes and effects of any modifications or upgrades are fully understood and incorporated into the FMEA and operational procedures, and

• meet the requirement of the classification society for annual survey.

Further details of IMCA’s recommendations for annual DP trials are to be found in IMCA M190.

A client-driven industry should pay attention to what the clients say and expect. This article has tried to point out the direction in which clients are headed. Coverage of topics is incomplete but the main areas are highlighted where we, as independent consultants, find most client interest and activity.

Of course prediction is, at best, informed guesswork, it is not an exact science, and the analysis here might be proved wrong. However, the trends over the last 40 years have shown a consistent rise in client expectations on all fronts, including the demands on DP OSVs. Owners who wish to respond positively to the trends and ‘stay ahead of the curve’ may draw some benefit from this paper and address the specific areas that are highlighted, namely:

• ensuring that their DP FMEAs meet the high standards that are increasingly expected by clients and not merely limited to the class-approved version

• developing and conducting annual DP trials of sufficient depth to demonstrate the operation, performance and fault tolerance of the DP system, and

• taking positive measures to ensure that people are suitably trained, qualified and experienced as well as taking account of innovative methods for the safe and controlled conduct of DP operations. OSJ

Related to this Story

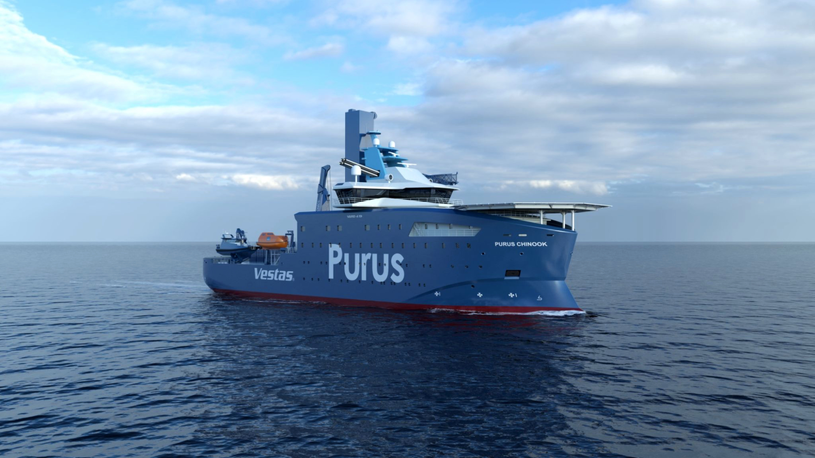

AI, digital twins help design cyber-secure, green SOVs

Events

LNG Shipping & Terminals Conference 2025

Vessel Optimisation Webinar Week

Marine Coatings Webinar Week

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.