Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Register to read more articles.

The ‘great’ compromise: IMO agrees to global carbon price for shipping

During an historic and sometimes heated debate, IMO agreed to a mandatory GHG pricing mechanism and a global fuel standard as part of its net-zero framework, setting in motion formal adoption in October 2025

With the aim of achieving net-zero emissions from international shipping by 2050, IMO has agreed to a mandatory carbon pricing mechanism and global fuel standard for the sector, setting the stage for its formal policy adoption in October.

But getting to an IMO Net Zero Framework was not easy. The regulatory text for the mid-term greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction measures was hammered out at two meetings of the Intersessional Working Group on GHG Reduction from Ships (ISWG-GHG) prior to MEPC 83.

With key member states unable to reach a consensus on proposed carbon pricing and emissions reduction targets, the deal was put to a rare vote on 11 April at plenary meeting of IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee’s 83rd session (MEPC 83) and passed with a majority of IMO’s 176 member states approving the draft policy text to be scheduled for adoption at an extraordinary meeting of the MEPC in October 2025.

Pay for emissions

The agreement would make shipping pay for its GHG emissions based on Direct compliance GHG Fuel Intensity (GFI) and Base target GFI thresholds. Carbon pricing would be linked to GFI of ship fuels used annually on a well-to-wake basis. If adopted, starting 2028, all ships of 5,000 gt and above would be required to either start using a less-carbon intensive fuels mix, or pay for the excess as determined by the GFI thresholds.

A ship continuing to use conventional marine fuel, for instance, would have to pay a US$380 fee on its most intensive emissions, and US$100 per tonne on remaining emissions above the lower Direct compliance GFI threshold.

Fees would be collected into an IMO Net-Zero Fund, with funding used to reward ships using zero or near-zero technologies and fuels and support climate protection efforts among the least developed countries and small-island developing states. Estimates project the carbon pricing system could generate US$10Bn or more annually.

The IMO Net Zero Framework will be included in a new Chapter 5 to the MARPOL Annex VI, and if adopted in October, would enter into force on 1 March 2027.

“IMO member states squandered a golden opportunity”

Included in the 63 countries and trading blocs which voted in favour of the IMO Net Zero Framework draft text were Brazil, China, the EU, India, Japan, Norway, Singapore, and South Korea. Large oil and gas-producing states, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Russia and Venezuela, were part of a group of 16 countries that voted against the measure. Some 25 other states abstained, including Argentina and Pacific Island states — which are among the countries considered most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Too little, too late

But Ministers from Fiji, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Seychelles, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, the Republic of Vanuatu, and a representative of the Republic of Palau refused to support the deal, saying it was “too little, too late to cut shipping emissions” and protect their island nations.

Instead, Pacific Islanders along with the Seychelles, Caribbean, African and Central American states, and the UK had proposed a universal carbon levy on GHG emissions.

Not perfect

Shipowners, for the most part, welcomed the new measures. The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) sees carbon pricing as critical to ensuring international shipping’s transition to net-zero GHG emissions by or about 2050.

“If formally adopted, shipping will be the first sector to have a globally agreed carbon price, something which ICS has been advocating for since COP 26 in 2021, when the industry agreed a net-zero 2050 target,” said ICS secretary general, Guy Platten.

But Mr Platten admitted the deal was “not perfect in every respect,” and was concerned that it “may not yet go far enough in providing the necessary certainty.” But he did thank member states and IMO for “achieving this agreement in challenging political circumstances.”

The most dramatic of those “circumstances” was created by the US, which stormed off, pulling out of the negotiations, while circulating a diplomatic message to the countries in attendance that it would not support any international environmental agreement that “unduly or unfairly burdens the US.”

“The deal is too little, too late to cut shipping emissions”

Politico reported that a letter sent by the US to many of the embassies in attendance threatened retaliatory measures against countries that imposed a carbon tax on US ships.

“Should such a blatantly unfair measure go forward, our government will consider reciprocal measures so as to offset any fees charged to US ships,” read the letter, according to Politico.

Signal on green fuels

The idea behind the carbon tax is the ‘polluters pay principal.’ Owners will be penalised for using fossil fuels, driving them towards lower carbon-intensive and alternative fuels, such as green versions of ammonia and methanol made with renewable energy.

Over the last few years, shipowners have invested billions of dollars in alternative fuel-capable newbuilds in preparation for the arrival of green fuels. But with the exception of LNG, progress has been slow on producing alternative fuels at scale and making them available at ports. LNG is available at more than 170 ports, with about 74 bunkering vessels in operation and another 30 under construction, according to DNV.

International shipping hopes its commitment to carbon pricing and fuels with lower carbon intensities sends a strong signal to energy producers to ramp up supplies of low- and zero-carbon fuel to the sector.

“Shipowners and energy producers need a workable, transparent, and simple-to-administer regulatory framework that will create the necessary incentives to accelerate the energy transition at the pace required,” said Mr Platten.

“We hope that this agreement will now provide the certainty which energy producers urgently need to de-risk their huge investment decisions,” he added.

Slammed by environmental groups

Environmental groups slammed the deal, saying it fell far short of the action that was needed to ensure international shipping meets its IMO GHG emissions reduction targets for 2023, 2040 and 2050.

Delaine McCullough, president of Clean Shipping Coalition, a group of NGOs that has observer status at IMO, said the IMO member states “squandered a golden opportunity” on maritime decarbonisation. “Instead of setting a strong energy efficiency regulation, combined with an ambitious fuel standard and sufficiently high price on all GHG emissions from ships, the IMO instead chose low ambition and business as usual,” she said.

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

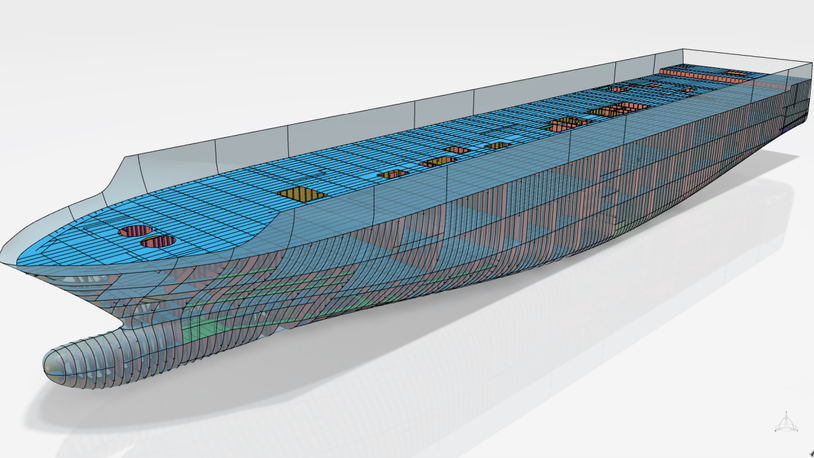

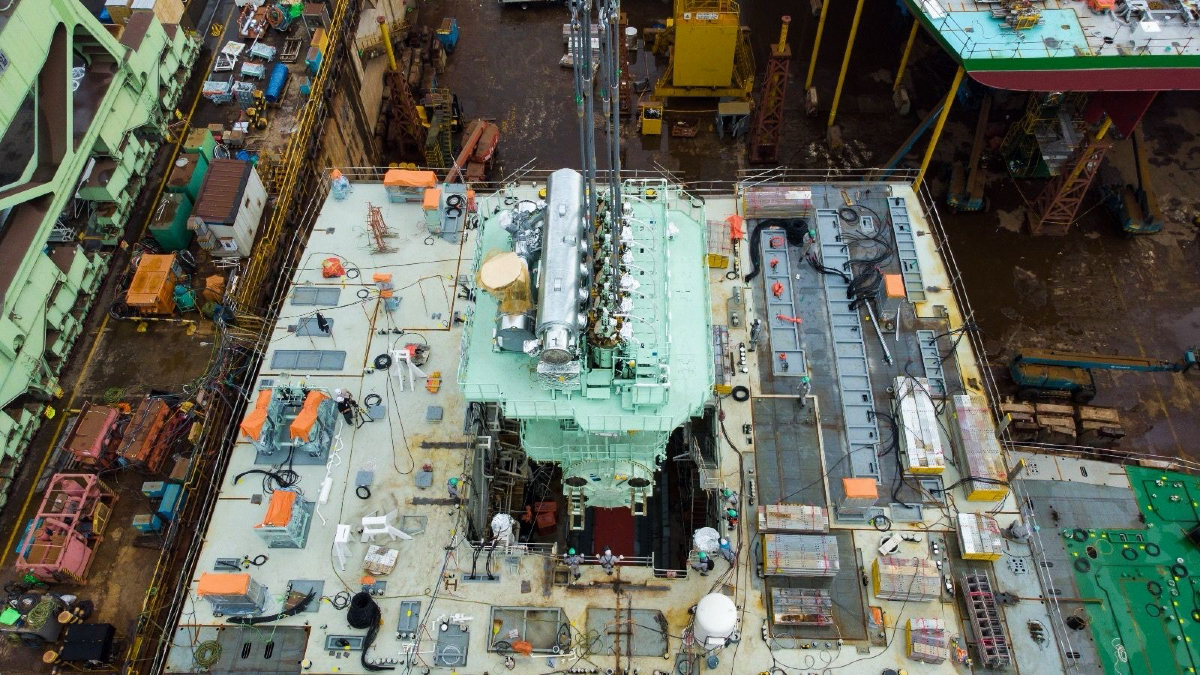

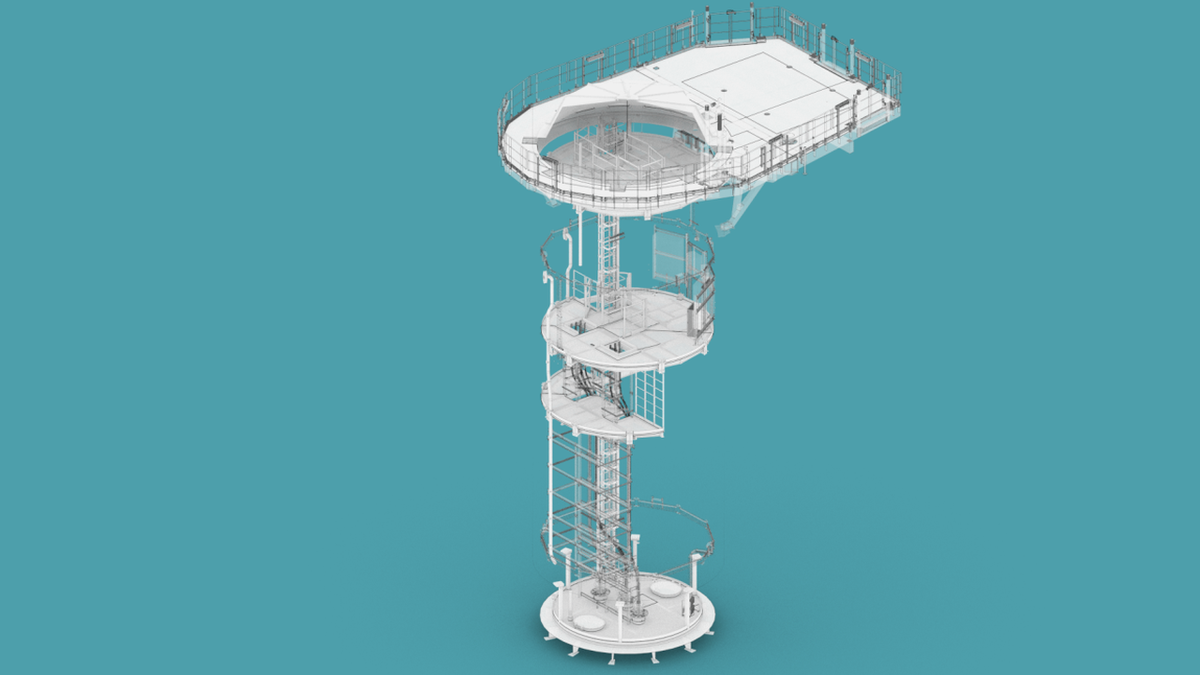

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.