Business Sectors

Contents

Marine air pollution: mitigating the effects on human health

The risks of air pollution to human health is a matter of public discourse and the role of ports - especially those in populated areas - is becoming increasingly and more intensively scrutinised

The Marine Air Pollution week was sponsored by the Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems Association (EGCSA), whose director Don Gregory opened the proceedings on Human Health with a view of the current situation in ports. “We know that an alternative compliance method for sulphur emission control is the application of exhaust gas cleaning systems. As well as reducing SOx to levels to lower levels than compliant fuel, these units can also remove other pollutants and condense gaseous pollutant compounds,” he said.

“Unfortunately, some ports have banned the use of open-loop scrubbers in the port. This appears to be for considerations of possible, but unsubstantiated, impacts on water quality while completely neglecting air quality issues,” he said. He noted that the exhaust gas cleaning technology had the ability to develop to include the removal of ultra-fine particulates, black carbon, while providing the benefit of lower overall CO2 emissions.

Consultant and former UK Environmental Agency director John Murlis highlighted the impact of pollution on human health. He noted that according the World Health Organisation (WHO), pollution is the now the largest single cause of excessive deaths, larger than smoking, alcohol or drug use. The top five causes of excessive death are air pollution, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, poor diet and inactivity. Air pollution is the only one of the top five that cannot be addressed through personal action. Reducing the risk of air pollution requires institutional approaches.

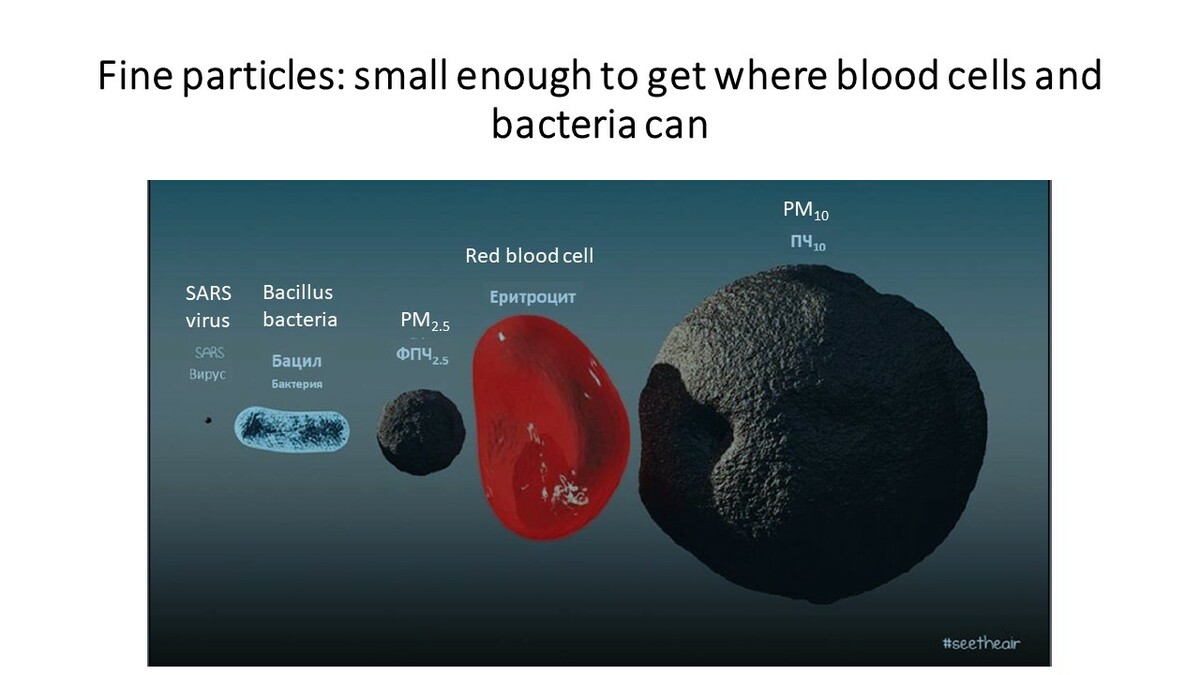

Mr Murlis pointed out that not only is air pollution a problem for everyone, the size of the particles makes a huge difference. The criterion measure measurement of particulate pollution is PM10 which means particles with a diameter of less than 10 micrometres (0.01 mm) – about the diameter of a human hair. Natural dust in the air, for example from sand, is in the coarse fraction of PM10, and people have to some extent adapted to it, but particulate air pollution from marine engines is mostly much smaller. PM2.5 is the metric used to characterise this smaller fraction in international emission inventories and appears to be far more harmful to human health. PM2.5 is about the size of bacillus bacteria and this fine faction of PM can easily enter the vital organs of the body.

Mr Murlis noted the literature indicates an association between excess mortality and the ambient concentration of PM2.5 particles in the air. He said even at levels of concentration below accepted international standards, there is a positive linear relationship between the excess mortality and the ambient concentration of PM2.5. There is also documented improvement of all kinds of health outcomes when air quality is improved. He highlighted the case of Ireland. When smoking indoors was banned in Ireland, there was an almost immediately drop in the number of people presenting with related illness: a 32% drop in strokes and a 26% reduction in ischaemic heart disease. The results of air pollution reductions are also evident over time. In the Harvard six cities study, the 15-year reduction in fine particles resulted in a 27% reduction in the risk of death from all causes.

Where do fine PM2.5 particulate come from? Mr Murlis listed the major land-based sources as:

- Biomass (fires, including forest clearing) 42%

- Industry (incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons) 10%

- Residential (heating and cooking) 24%

- On road diesel engines 14%

- Off road diesel engines 10%

These major sources are increasingly becoming subject to controls with consequent large-scale reductions in the emission of PM2.5. He quoted the example of Poland, which is spending €35Bn (US$38Bn) investing in replacing traditional Polish home solid fuel heating systems with low PM2.5 versions.

The other major source that has moved toward lower PM2.5 emissions is road use. Steps include diesel particulate filters which reduce PM in exhaust by 99%.

These changes in land-based source emissions have thrown the spotlight onto shipping. “Shipping is a major source of air pollution emissions and PM is a major component of that. As other sectors make reductions, shipping begins to stick out as an outlying source. The regulators globally have noted this and are turning their attention to the shipping sector,” said Mr Murlis.

University of Naples Federico II Professor of Sustainable Unit Operations and Technologies for Pollution Control Professor Francesco Di Natale is a chemical engineer with 18 years of experience in scientific and industrial projects aimed at developing sustainable pollution control technologies for industrial and marine. His presentation at the webinar was aimed at examining how much IMO Marpol Annex VI reduces the toxicology of air pollution.

He noted that diesel exhaust emissions are tightly regulated in the European Union as diesel emissions contain noxious substances, including:

- Sulphur compounds: SO2.

- Nitrogen oxides: NO, NO2.

- Ashes (PM).

- Carbon based compounds: CO, CO2.

- Volatile organic compounds: benzene, acrolein, formaldehydes, PAHs.

- Condensed organic compounds: diesel particulate matter, elemental carbon, organic carbon, non-volatile organic carbons.

These are known to be hazardous to human health. The EU already controls the emissions through the following regulations:

- Euro VI regulation for light duty diesel engines.

- 2016/1628/EU Directive for non-road heavy duty diesel engine, included Inland waterways shipping.

- 2019/137/EU Directive.

Apart from inland waterways, these do not cover the emissions from heavy marine engines. Professor Di Natale said “For marine fuel, the composition of the pollutants in enriched by the presence of other substances related to the quality of the heavy fuel oil. There are sulphates, heavier organic compounds and cat fines.”

Marpol VI does not cover volatile organic compounds (VOC) or diesel particulate matter (DPM). The problem for regulators is how to define the limits. Professor Di Natale commented that defining the limits of organic pollutants was a difficult issue. The Marpol VI regulation controls the mass distribution of larger particles, but this is the problem. “We know the larger particles are not as toxic as the finest particles in terms of their intrinsic chemical composition. Scientific evidence shows the toxicity of particles is proportional to their surface area. Therefore, to control the toxicity of particles, we should control the surface area of the particles.”

He noted that even for specialist laboratories it is difficult to control the finer particles surface area. From a practical point of view, Marpol VI should place a cap on the mass and number of particles as done by other EU regulations, as Euro VI for passenger cars and 2016/1628/EU for heavy-duty engines, included inland waterways vessels. The very fine particles are able to enter the bloodstream and reach vital organs, including the heart, lungs, brain and also foetus.

In conclusion, Professor Di Natale noted several aspects:

- Diesel engine exhaust has been classified as toxic by regulators.

- Marine fuel is more toxic than diesel fuel.

- Scientific studies show that shipping can increase local air pollution by around 5% to 25% in harbour cities.

- Marpol VI controls only some of the pollutants.

His suggestions for updating or revising regulations were:

- New regulations to control organic emissions, particular organic compounds from marine diesel.

- Next-generation exhaust gas cleaning systems capable of controlling mass and number concentrations of particles in the air emissions.

Questions

Is the panel optimistic when it comes to the prospects for shipping to get its house in order?

Mr Murlis replied, “I am optimistic. Firstly, although the investment looks large, it is fairly modest compared with other investments to be made in shipping. Secondly, shipping will want to defend its position and will anticipate what it is the regulators will be asking, so will make changes on its own terms.”

Professor Di Natale replied, “Shipping needs to be regulated.” He acknowledged the investment criteria but noted that other industries had gone down this road and it was time for shipping to catch up. “People are becoming aware of the risks associated with air pollution, also about that from shipping. This is one of reasons that I am optimistic that shipping will introduce (better) air quality regulations,” he said.

Mr Gregory replied, “I am optimistic and pessimistic. The shipping industry is becoming used to complying with new regulations and fitting on new technology and operating new systems to reduce air or water pollution. However, I am pessimistic in the process that to create these regulations, the whole process needs to be overhauled. The IMO process is haphazard. The whole process is entrenched in long debates and arguments which go on for years and years.”

Mr Gregory had a question for his two fellow panellists.

Is there a link between air pollution and the susceptibility of succumbing to the Covid-19 coronavirus?

Professor Di Natale replied that this is a complex question, and that societies are beginning to understand how much atmospheric air quality is important for health and safety. “We were hit hard in Italy, and there probably was a co-impact from air pollution because air pollution is higher in high population density areas and is a cause of stress and even of death for the exposed population,” he said. However, it is not clear whether there is a one-to-one correlation between air pollution and spreading of Covid-19 coronavirus.

Mr Murlis replied, “There have been studies in Italy and the United States where scientists have looked at the relationship between air pollution levels and particulate air pollution levels, and health with regards outcomes of those infected with the coronavirus. There is some evidence emerging that where there has been higher levels of air pollution, there have been worse health outcomes.”

Poll

According to polls of the webinar attendees, technology to abate PM and VOCs in exhaust gas emissions still needs further development and commercialising.

When asked ’How much time do you think is needed for EGCS providers to put on the market off-the-shelf units to control diesel particulate matter on both a weight and number metric?’, only 4% said they felt the technology was ready. Around 52% said it was three years away, 22% said five years away and 22% more than five years away.

When asked how long it would be before VOC control technology is commercially available, 40% of the audience said more than five years. Another 27% said five years, 13% said three years and 20% said VOC control technology would be commercially available in one year.

The roll out of PM and VOC abatement technology could be accelerated. Equipment is already available for shuttle tankers to recycle VOCs from cargo, which could potentially be adapted for emissions abatement. There are also combinations of exhaust gas cleaning technologies that can be adapted, such as selective catalytic reduction (SCR) equipment for removing NOx from engine exhaust gases.

When asked ‘Do you think a combined scrubber and SCR unit is a mature EGCS configuration?’ 60% of the audience said yes, another 20% said no and 20% were not sure.

Mr Gregory called on IMO to work faster in introducing legislation, such as Marpol Annex VI regulations, on cutting marine air pollution further.

However, 50% of the webinar audience thought Marpol Annex VI regulations were effectively cutting air emissions toxicity.

Key takeaways

Mr Murlis “My takeaway message is that air pollution is a major health risk and diesel is a major contributor to that. If we improve air quality by reducing emissions and particularly diesel emissions, we will get improved health outcomes. It is high time that marine stepped up to mark.”

Professor Di Natale “The lessons learned from other sectors and confirmed by scientific evidence is that fuel switching is not an option to reduce the carbon-based components of particulate matter or volatile organic compounds. What we need is the introduction of exhaust gas cleaning system for ships to produce compliance with the other sectors.”

Mr Gregory “The challenge is for IMO to rapidly change its processes and the time it takes to get to regulation. The marine industry has to develop the technology. We need to reduce air pollution from ships to zero. We cannot afford to wait 20 years, which is what it has taken for the Marpol Annex Vi process to go through and implemented. I think a five-year process is what we should be working towards.”

Related to this Story

Events

Reefer container market outlook: Trade disruption, demand shifts & the role of technology

Asia Maritime & Offshore Webinar Week 2025

Marine Lubricants Webinar Week 2025

CO2 Shipping & Terminals Conference 2025

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.