Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Wind-assisted propulsion: return of the age of sail?

Shipowners from Maersk to Union Maritime are trying to harness fuel and emissions savings through investments in various wind-assisted ship propulsion systems

Wind is free, and there is usually plenty of it. So why not use it?

That appears to be the growing conclusion of the shipping industry as it chases lower emissions and fuel savings.

Simultaneously, the benefits are being quantified. In mid-2025, Singapore’s Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation (GCMD) compiled numbers based on a four-month trial with Pacific Sentinel, an MR tanker trading on the spot market around the Americas. Equipped with three 22m-high suction sails, the tanker posted “instantaneous power savings” of over 7%.

But as GCMD acknowledges, the ship ran into near headwinds most of the time. “If the vessel experienced more favourable wind conditions, the savings could be higher,” the study concluded.

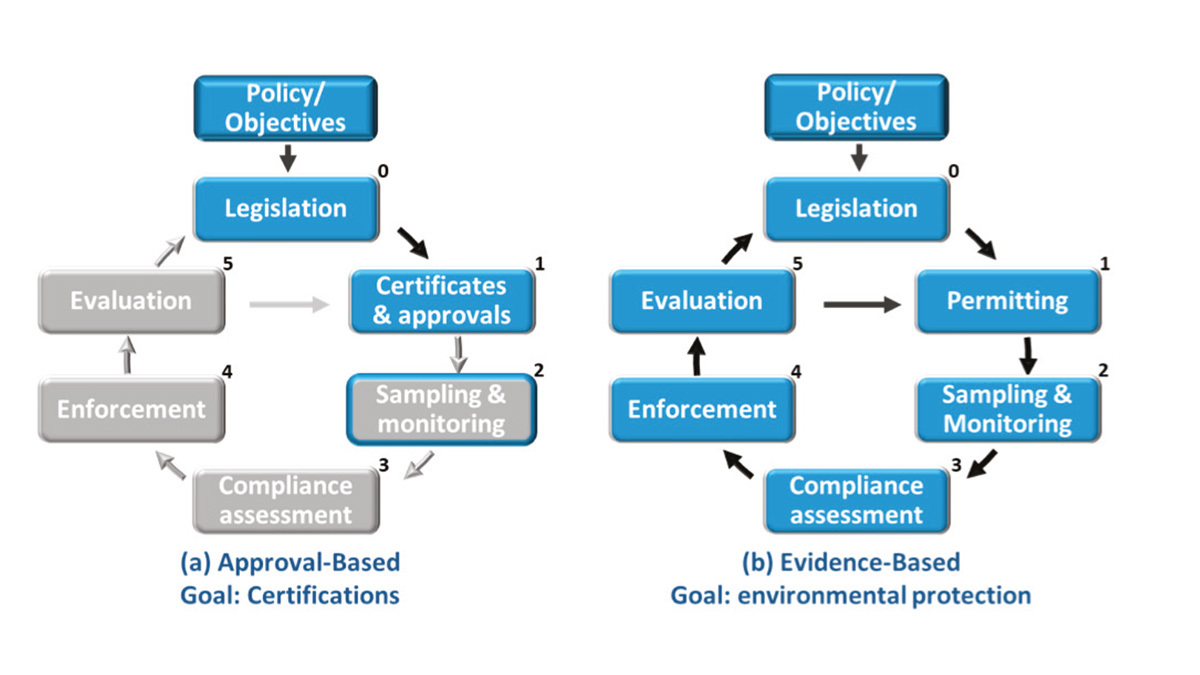

As GCMD explained, the Pacific Sentinel research is just the start of a more comprehensive base of evidence that captures the full performance envelope of wind-assisted propulsion systems (WAPS). “Establishing a credible, standardised framework for WAPS measurement and verification is a critical step toward scaling wind-assisted propulsion across the global fleet, turning empirical results into actionable confidence for shipowners, financiers, and regulators alike,” explained the maritime think tank.

Promising numbers are emerging elsewhere too.

Finland’s Norsepower estimates that its rotor sails, which are spinning vertical cylinders that propel the ship through the Magnus effect, are posting fuel savings of 5 to 25%. The wide variation in these and other numbers provided by WAPS manufacturers is explained mainly by weather patterns and the vessel’s route. WAPS technology is not practical for everyone, such as container ships, which have limited deck space. However, the technology is good enough for Japan’s Idemitsu Tanker group, which signed with Norsepower in late 2025 to install rotors on two VLCCs to be built by Japan Marine and Nihon Shipyard for launch in 2028. Each will carry two 35m-tall sails.

“The tanker posted instantaneous power savings”

The Idemitsu contract is Norsepower’s first for VLCCs and chief executive, Heikki Pöntynen, described it as “a defining moment for Norsepower and for wind propulsion in global shipping.” Japan is now Norsepower’s single biggest market.

UK’s Anemoi Marine Technologies is also finding clients for its rotor sails, most recently Berge Meru, a 208,000-dwt Newcastlemax that boasts four of these 35-m-tall towers, installed last December.

Next up, Union Maritime has signed with Anemoi for rotors on two 18,500-dwt newbuild chemical tankers under construction at China’s Wuhu Shipyard, as the London-headquartered shipping group aims to find at least 5% of its energy from zero- or low-emissions sources by 2030.

Anemoi, which has a factory in China, can probably claim the biggest retrofit so far. Last October it completed the installation of no less than five rotor sails on a 400,000-dwt ore carrier, NSU Tubarao, one of four very large ore carriers (VLOCs).

In other contracts, already in action on two bulk carriers is Mitsui OSK’s Wind Challenger, another rotor-type sail that also recently won Lloyd’s Register (LR) approval in principle for installation on a 174,000 m3 LNG carrier in another breakthrough for wind propulsion. LR’s global gas segment director, Panos Mitrou, believes there is a trend on the horizon: “Wind-assisted propulsion technologies are emerging as an important part of the industry’s journey to decarbonisation.”

Maersk’s five

In other big contracts, in late January Maersk launched a five-vessel retrofit of its suction sails with an installation on Maersk Trieste, an MR tanker. Maersk chose four 24m-high suction sails from Spain’s bound4blue, with another 16 to be mounted on the remaining four tankers.

Critical in the retrofit of any energy-saving technologies is reducing downtime. Prolonged dry-docking times equate to lost revenue. WAPS manufacturers are learning all the time.

The Maersk installation was done in a two-step plug-and-play process designed to reduce downtime and some retrofits can be done in a single day. As bound4blue explains, preliminary work began in the Yu Lian shipyard in Shenzhen in the form of deck pedestals and electrical modifications. In the final step, the sails were hoisted onboard and connected up at Belgium’s EDR shipyard.

The Spanish operation has come a long way since its first commission, an installation on a Panamanian fishing vessel in 2021. Besides Maersk, its customers include Eastern Pacific Shipping, Marubeni, Klaveness, Odfjell, BW Epic Kosan and Louis Dreyfus.

“We’ve passed the initial scepticism”

bound4blue co-founder and deputy chief executive, Cristina Aleixendri, described the industry’s change in attitude: “Looking back, I’d say one of the biggest milestones was closing our first major agreements with international shipowners at a time when wind propulsion was still considered ‘nice to have’ rather than a solution for today. It helped shift the perception of the technology from prototype to real, scalable impact and it set us on the path to become a reference in the sector.”

And echoing other believers in wind propulsion, she added: “As fuel prices rise and regulations tighten, energy efficiency will become non-negotiable and wind offers efficiency gains without waiting for future fuels to scale.”

America’s Cup

A newcomer in heavy-duty commercial wind propulsion, Portsmouth-headquartered BAR Technologies has taken a different approach with its WindWings since it was established in 2017.

First installed on the 80,000-dwt bulk carrier, the Cargill-chartered Pyxis Ocean in 2023, the sail-like WindWings emerged from the America’s Cup. Technically, BAR describes them as “a three-element rigid wing that delivers two and a half times the thrust of a single-element wing.” Like real sails, they adjust themselves constantly according to the direction and power of the wind. BAR does not make the sails; its 50-strong team of mathematicians, engineers, scientists and naval architects designs and develops them for manufacture.

WindWings are robust, constructed out of wind turbine materials. They are good for winds of up to 40 knots, depowering automatically above that strength, and have a working life of 25 years, roughly the lifetime of the ship. They fold down at the push of a button, for instance in port and in congested shipping lanes, and they require much less power than alternatives. WindWings vary between 20-m and 37.5m in height, according to the size of the vessel.

So far BAR has found its clients in the bulk carrier and tanker fleet but it is moving into smaller vessels and its 2026 order book is filling up rapidly on the back of real-life numbers.

BAR Technologies’ sales manager (and engineer) Tom James said: “We’ve passed the initial scepticism.” WindWings’ predicted savings are based on calculations drawn from a wide range of ships and sailing conditions. “Average fuel savings for each wing per day work out at 1.5 tons and average CO2 savings at over 4.7 tonnes,” he noted.

There is no end to innovation. Tyre giant Michelin has come up with one of the more startling systems; an inflatable but rigid sail hanging off a fully retractable telescopic mast. The sail inflates through automatic fans as the mast rises. The French company says its Wing Sail is suitable for tankers, bulkers, general cargo, ro-ro and passenger vessels. A 100-m2 version has been tested on a merchant ship and, starting this year, Michelin plans to commercialise 800-m2 sails.

Aerodynamic ships

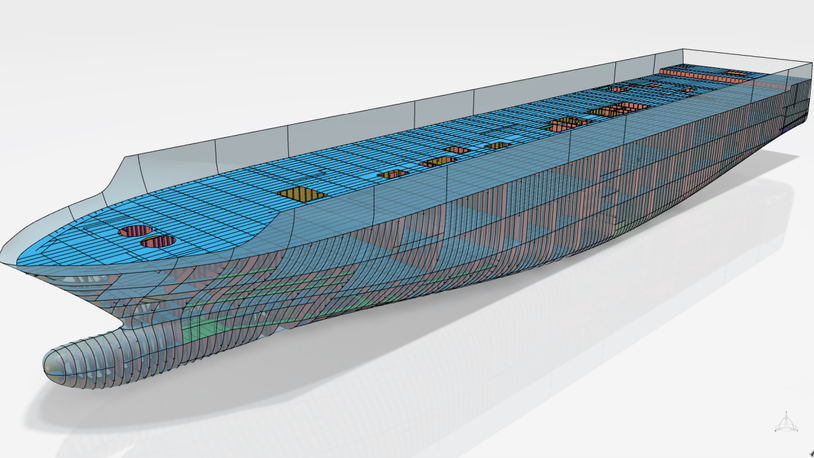

Looking ahead, at least three wind propulsion companies are experimenting with more aerodynamic ships that are in effect designed around the sails.

In the Bluetech SeaWasp project, US-listed International Seaways, Bluetech Finland and Norsepower simulated the redesign of an MR tanker working the San Francisco-South Korea route. Calculations showed that at an average propulsion power of 876 kW, the ship delivered annual fuel savings of nearly 600 metric tonnes, equivalent to about US$240,000-US$360,000, from its two 35m-tall rotors.

So what redesigns were made? Above the waterline Bluetech’s naval architects came up with a “more aero” superstructure and semi-enclosed mooring stations. Below the waterline a new fin system “significantly increases power saving potential” through improved hydrodynamics. Bluetech’s head of hydrodynamics, Juha Hanhinen, said she was “surprised by how significant the fin effect was — it creates a powerful case for combining hydrodynamic improvements with wind propulsion.”

Although it is early days, Bluetech’s director of energy savings solutions, Sam Robin, believes the SeaWasp concept shows that wind propulsion should not be an afterthought: “It can be central to the way ships of the future are designed.”

Similarly, in Japan, Mitsui OSK is also working with universities and the aerospace industry on a more aerodynamic hull shape that is intended to make its Wind Challenger sail more efficient. And so is BAR with its AeroBridge package, that reshapes the superstructure. And like some of its competitors, BAR also offers routing software that maximises the value of the sail.

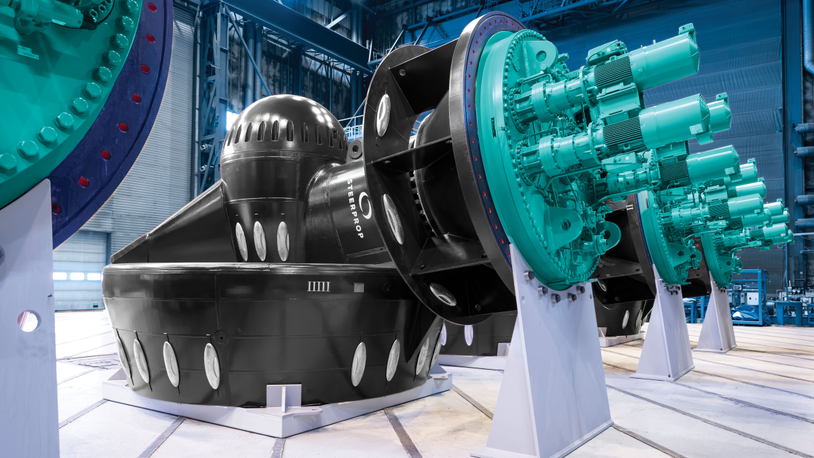

There are fewer sceptics of wind propulsion now. Wärtsilä, which offers Anemoi rotors, calculates that wind propulsion can save up to a third of normal fuel, particularly when vessels consistently sail long routes at lower speeds. And as Bryan Comer, the head of the non-profit International Council on Clean Transportation predicts: “Ultimately, wind-assisted propulsion is going to help with the global transition for even the largest segments of the cargo shipping sector.”

Related to this Story

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.