Business Sectors

Events

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

Contents

Register to read more articles.

Risk and regulation mean industry faces alternative-fuel paralysis

As operators wait for a certainty on alternative fuels that remains elusive, the cost of hesitation mounts and first movers risk betting on the wrong technology

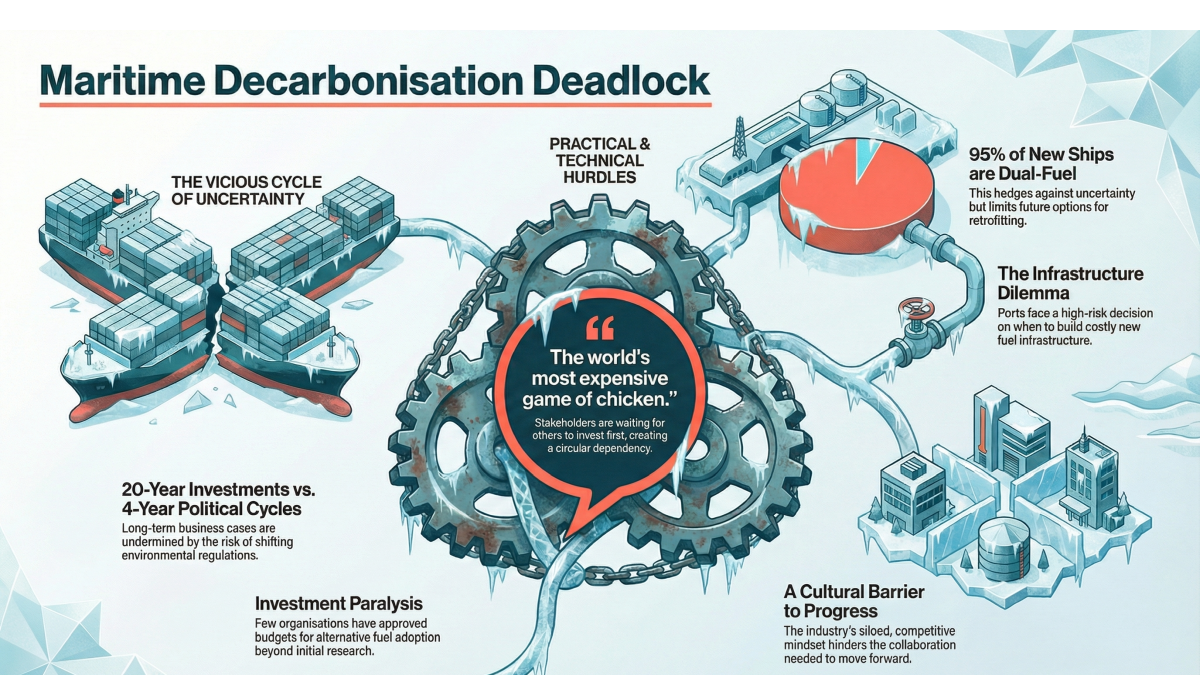

The maritime industry finds itself locked in "the world’s most expensive game of chicken," where vessel operators, fuel suppliers and port developers each wait for others to make the first commitment to alternative fuel infrastructure.

Participants from the worlds of vessel chartering, ownership, ports, engine manufacturing, marine fuels and lubricants, and industry associations, gave this assessment during a roundtable discussion sponsored by Caterpillar Motoren at Riviera’s Maritime Decarbonisation Conference Europe. The discussion, held under the Chatham House Rule, brought together senior figures to share frank views on the industry’s decarbonisation challenges.

Market deadlock deepens

The current standstill extends well beyond simple commercial caution. According to one fuel developer present at the meeting, the industry faces a fundamental timing mismatch: maritime operators are content to rely on biofuels until 2035 before considering e-fuels, yet without investment today, there will be minimal e-fuel supply available when that timeline arrives.

"The big problem is that if we don’t invest today, there will be very limited supply of e-fuels in 2035," noted one participant representing the e-fuel sector. This creates a circular dependency, where fuel producers need committed demand to justify investment, while ship operators require guaranteed supply before committing to vessel modifications.

Several attendees highlighted that formal business cases for alternative fuel investment remain rare. When asked who had approved budgets for alternative fuel adoption, only a handful of participants indicated their organisations had moved beyond the planning stage. One lubricant additives specialist confirmed their company had allocated research budgets, but primarily to understand failure modes and engine issues rather than for direct fuel adoption.

Regulatory uncertainty compounds commercial risk

The challenge extends beyond pure economics. Participants expressed significant concern about building business cases with 20-year payback periods when political cycles run just four years and recent elections globally have raised questions about the permanence of environmental regulations.

"How do you build a business case with a 20-year payback when the political cycle is four years?" posed one industry observer, capturing a sentiment that resonated throughout the discussion.

The International Maritime Organization’s evolving framework adds another layer of complexity. As one participant explained, IMO faces unique constraints, "It only has one lever, and that is the ship. It can’t tell the countries what to do." This limitation means the organisation must attempt to regulate an entire supply chain through pressure on just one element: the vessel itself.

European regulations presented their own challenges. The EU’s approach to emissions regulation, which applies similar philosophies across all sectors from automotive to shipping, may not align well with maritime’s specific characteristics. One e-fuels advocate reflected that while stakeholders initially supported regulation on the principle that "regulation is better than no regulation", four years later the sector has seen minimal final investment decisions, with regulatory uncertainty still cited as the primary barrier.

Infrastructure investment dilemma

Port authorities find themselves in a particularly challenging position. As one major European port representative explained, the ecosystem requires facilitation through major infrastructure projects such as hydrogen backbones and carbon capture facilities. Yet these investments require co-ordination across multiple stakeholders, none of whom want to move first.

"If a port authority doesn’t take the lead to bring parties together and also wants to take a risk, then nothing starts moving," the port representative observed. However, timing such investments proves crucial; move too early and the infrastructure sits idle; move too late and the port loses competitive advantage.

The comparison with LNG adoption proved instructive. Several participants noted that LNG benefited from decades of operational experience on gas carriers before transitioning to fuel use, plus the crucial backing of major oil companies. "When LNG was being introduced, fossil LNG had backup from Shell to bootstrap this new fuel supply chain into existence," one attendee recalled. "That is something we don’t have in our industry today."

Technology pathways remain contested

The discussion revealed deep uncertainty about which technological pathway will prevail. Orderbooks show that while operators are investing in new tonnage, approximately 95% of newbuilds are specified as dual-fuel vessels, essentially a hedge against uncertainty. "They’re not sure what’s going to be coming along, but they do know, well, at least I can burn VLSFO," explained one participant.

This hedging strategy has implications for future flexibility. As one attendee noted, VLSFO-capable engines can only be retrofitted to burn certain alternative fuels, limiting future options. The infrastructure requirements for converting from liquid fuels to gases present challenges around tankage and storage.

Methanol emerged as a relatively uncontroversial option from a technical perspective, with participants noting minimal concerns about the technology itself. However, challenges around density, production costs and molecule availability persist. Meanwhile, ammonia faces more significant technical hurdles, though the existence of trained crews from ammonia carriers provides some foundation for adoption.

One solid hydrogen carrier developer expressed urgency about market timing, "We have a safe carrier and one of the densest carriers on the market. We can store double the amounts of other fuels, but if we’re not fast enough, no one will be interested."

Geographic fragmentation threatens global solutions

Participants highlighted how regional differences in fuel availability could fragment shipping routes. One delegate suggested the industry might see the emergence of fuel-specific corridors, "You will almost end up with bulk breakers because the bigger ships may run on certain fuel types but they will only be able to travel between A, B, C and D.

This geographic constraint could see smaller vessels adopting different fuels based on localised production. E-fuels might be produced in Brazil, Canada, France and South Africa, creating regional markets rather than global solutions. The resulting patchwork would fundamentally alter traditional shipping patterns.

The situation becomes more complex when considering land-based power generation in many regions continues to burn 3.5% sulphur fuel oil without regulation.

"While we talk about maritime decarbonisation, you’ve got other sectors that say, well actually, no, we’re not changing. We’re not regulated," one participant observed.

Breaking the impasse

When asked what would most effectively break the current deadlock, participants split between several options, with government mandates and compliance enforcement receiving the most support. However, scepticism about international enforcement capability tempered enthusiasm for this approach.

Some advocated for co-ordinated commitments from major operators, arguing that without acceptance of specific fuel types, the industry cannot stake claims on bunkering infrastructure or engine development pathways. "Without an acceptance right now, you’re producing 18 different engine types," one participant calculated.

Others suggested creative risk-sharing mechanisms might help. The Zero Emission Maritime Buyers Alliance and structures like H2Global’s double-sided auctions, where public entities cover premiums, were cited as potential models. One participant described emerging creative off-take structures where "a portion of the output is indexed to the electricity price, and a portion is going to be spot."

The role of major customers emerged as potentially crucial. Several participants noted that focusing on clients with high-margin products, where fuel costs represent a minimal percentage of product value, might enable first movers to absorb additional costs. "If you get a pair of shoes, it’s maybe one or two cents [extra] per pair," explained one fuel developer.

Collaboration versus competition

Perhaps the most significant barrier identified was cultural rather than technical or economic. Multiple participants observed what they described as a siloed, tunnel vision preventing necessary collaboration. "There seems to be almost a blinkered wall. I can’t be seen to be working with them," one attendee noted. "Well actually it’s not, because if you work together, you produce a focused endpoint."

The industry’s traditional competitive dynamics appear poorly suited to the challenge at hand. As one participant summarised, "The deadlock isn’t going to break itself. No regulator is going to create perfect certainty. No fuel supplier is going to build infrastructure on pure speculation."

Strategic autonomy adds urgency

Recent geopolitical tensions have added another dimension to the debate. Port authorities report that strategic autonomy has become as important as energy transition in investment decisions. This shift might accelerate decision-making, though it also adds complexity to fuel choice considerations.

The training and expertise question looms large for certain pathways. One fleet operator noted the global shortage of steam engineers, which could complicate any shift toward technologies requiring steam expertise, including potential small modular reactors. "If you’re under 65 and you’ve got a steam ticket, LNG carrier companies will pay you absolute superstar wages," the operator observed.

Looking ahead, participants acknowledged that while the deadlock is real and expensive, waiting offers no solution. "You can’t wait your way to certainty. You can only wait your way to irrelevance," as one observer put it. The challenge now is converting that recognition into co-ordinated action across an industry more accustomed to competition than collaboration.

Sign up for Riviera’s series of technical and operational webinars and conferences:

- Register to attend by visiting our events page.

- Watch recordings from all of our webinars in the webinar library.

Related to this Story

NZF delay: what next for IMO’s headline policy?

Events

Maritime Regulations Webinar Week

Floating energy: successfully unlocking stranded gas using FLNGs and FSRUs

© 2024 Riviera Maritime Media Ltd.